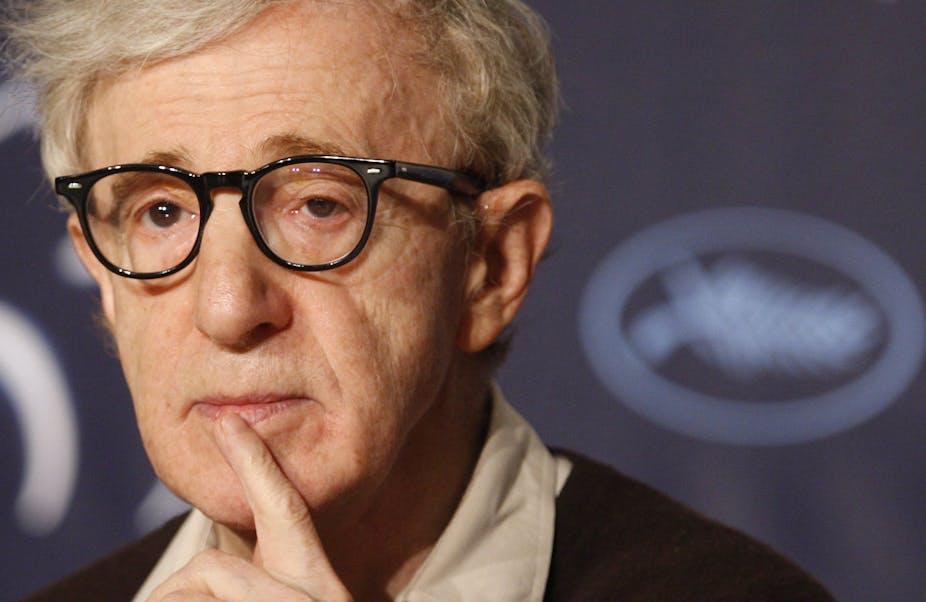

Last week, Woody Allen’s adopted daughter Dylan Farrow published an open letter in The New York Times accusing him of child sexual abuse. These allegations were first aired in the early 1990s in the context of an acrimonious split between Allen and Mia Farrow – Dylan’s mother – after Mia Farrow discovered naked photographs that Allen had taken of her adopted daughter Soon-Yi.

The allegation that Allen sexually abused Dylan was not tested in court as the judge ruled that she, then only seven years old, was too “fragile” for a trial.

Allen has denied this allegation and continues to do so. He claims that Dylan’s accusations were manufactured by her “vengeful” mother. Farrow’s brother Ronan breathed new life into them when he tweeted his objection to Allen’s lifetime achievement award at the Golden Globes, which read in part:

..did they put the part where a woman publicly confirmed he molested her at age 7?

Dylan Farrow’s open letter gave, for the first time, her own account.

It has been claimed that, since the allegations against Allen have not been proven in a court of law, there is a moral and legal imperative to give him “any benefit of the doubt”. Other journalists have gone further, stating that the decision not to proceed to trial “exonerates” Allen and calls Dylan Farrow’s motives and mental competency into question. Author Stephen King claimed that Farrow’s open letter was an act of “palpable bitchery”.

However, the presumption that Allen is innocent does not require the mistreatment of Dylan Farrow. Nor does it mean that her allegations are meaningless or unimportant.

The presumption that people are innocent of an allegation until proven guilty in a court of law is integral to due process, which ensures that allegations are treated by the legal system and media in a fair and equitable manner. It is important to note that the presumption of innocence is a procedural rather than a substantive principle: that is, it pertains to the process by which justice is achieved, rather than the nature of justice itself.

“Due process” includes the application of criteria by the courts and police that inevitably exclude some forms of suffering from public consideration. This results at times in outcomes that many do not consider just, fair or reasonable.

Child sexual abuse is the key example of this. Many victims do not articulate their experiences to others and so they never reach the threshold that would bring their abuse to public attention. However, those children who do disclose have routinely been considered too vulnerable or untrustworthy for the court process, although recent law reform holds out hope.

In the case of Dylan Farrow, the decision by a judge not to proceed to a criminal trial was based on concern that she would find the experience traumatising.

Victims must then contend with a doubled injury: the harm of abuse and the unsupportive response of authorities. While we tend to focus on the harm of abuse itself, this second injury – the lack of social support and validation – has long-term consequences.

Farrow describes the guilt and self-blame that resulted from the decision not to proceed to trial. While the presumption of Allen’s innocence has legal force, her own recollections of abuse have no such public standing and are transformed into a private, personal matter.

This quarantining of suffering in the private sphere can be corrosive. Farrow has described her battles with eating disorders and self-harm. However, it serves to shield others from the ethical complexities and ambiguities of abuse.

In her open letter, Dylan Farrow asked actors who have worked with Allen, such as Cate Blanchett and Alec Baldwin, how they would feel if something similar happened to their children. Both Blanchett and Baldwin have responded indirectly by characterising Farrow’s allegations as a “family” matter. This in effect denies the public and social significance that Farrow believes her claims deserve.

Unproven allegations of sexual abuse such as Farrow’s place journalists and public figures in a bind. They are required to put the presumption of innocence into practice in what they write and say, but the status of the victim and her allegation is unresolved.

The mixed response to Dylan Farrow’s allegation illustrates this quandary. Some media coverage has been sympathetic to Dylan while calling into question Allen’s honour. Others have upheld Allen’s innocence and discerned a veritable conspiracy against him.

Many credible allegations of wrongdoing are never tested in a court of law, as the current Royal Commission into child sexual abuse in Australia makes clear. This poses pressing questions that are not answered by another round of “he said, she said” or dismissive references to the allegations as a private matter.

Honouring the rights of the accused while giving weight to testimony of abuse does not have to be a zero-sum game. But it is clear that we have yet to develop an ethical framework that can properly do both at the same time.