World-first field trials of a new technique to stop mosquitoes passing the dangerous and painful dengue virus onto humans have been declared a success, with plans afoot to roll out the method in dengue-plagued Southeast Asia and Brazil.

Dengue fever, also known as breakbone fever for the intense joint-pain it causes, affects 50 million people a year in over 100 countries and can be fatal. Hospitalisation is often required, putting an enormous financial strain on poor communities in the tropics.

Dengue is transmitted by the bite of the mosquito Aedes aegypti but Australian scientists may have found a way to stop the insects from becoming vectors.

The breakthrough came in the form of a naturally occurring bacteria strain called Wolbachia, which infects many insects and is passed onto offspring but is not normally found in wild Aedes aegypti mosquito populations.

Scientists have shown that Wolbachia infection disrupts the dengue virus’ ability to grow in a mosquito and successfully infected mosquitoes with the bacteria in the lab.

Now they may have found a way to spread Wolbachia among wild mosquito populations, effectively dengue-proofing the insects so they are unable to pass the virus onto humans.

“What we are creating is a vaccine for the mosquito rather than the people,” said Professor Scott O'Neill, Dean of the Faculty of Science, Monash University and a member of the research team that trialed the technique.

In a new paper published in the journal Nature, the researchers describe field trials conducted in Yorkeys Knob and Gordonvale near Cairns in January this year.

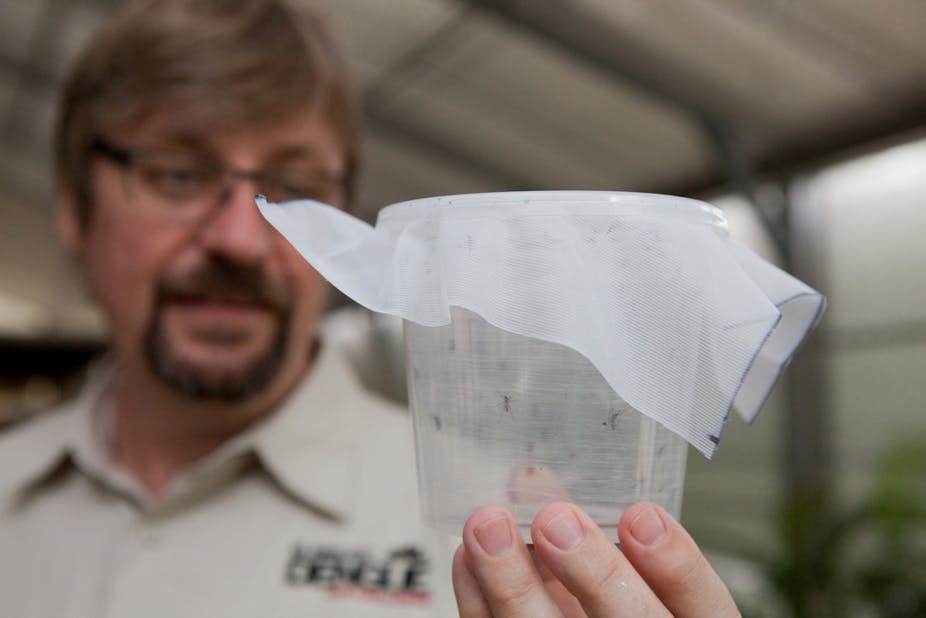

With the consent of residents, almost 300,000 Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes were released across the two locations over 10 weeks.

Five weeks after the last round were released, 100% of the Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in Yorkeys Knob and 90% of those in Gordonvale were found to be carrying Wolbachia – proving that the bacteria that prevents the insects from becoming dengue-carriers could be spread easily and cheaply to wild mosquito populations.

“It’s a very exciting result,” said Professor O'Neill. “We expect these regions should have a much reduced risk of dengue transmission within them.”

The researchers, who are working with scientists from Brazil, Thailand and Vietnam and the US as part of the Eliminate Dengue project, now plan field trials in Brazil, Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam.

A risk assessment was completed before the Australian trials and will be done again before the field experiments overseas.

Professor O'Neill admitted that researchers still don’t know exactly why Wolbachia appears to block dengue from growing inside mosquitoes and that there was always a risk Aedes aegypti could grow resistant to the bacterium.

“With any control measure you are working with there’s the possibility of resistance developing,” he said.

“But we don’t know the time frame over which that might occur. In our lab we have been trying to mimic resistance development… So far haven’t been able to do that.”

The field trials offered hope to communities that have struggled to control dengue fever with expensive neighbourhood fumigation schemes, Professor O'Neill said.

“People are very tired of dengue fever and very fearful of it, the people who live in affected communities. They are quite eager to see the development of new measures,” he said.

Professor O'Neill’s co-researcher, Professor Scott Ritchie from James Cook University, said the team was quietly confident the field trials would work.

“It’s like having the ace in your sleeve. You know you have a great hand and it’s going to work but, I tell you what, we were pleased as punch when it worked out.”