It’s the kind of moment a researcher never forgets. I was in the British Film Institute archive and had just pressed play on a fragile-looking VHS tape which, I hoped, would contain footage of the poet WS Graham (1918-86).

A friend of Dylan Thomas and protege of TS Eliot, Graham was feted on both sides of the Atlantic while still young, only for literary fashion to change in the 1950s. From 1955 until his death, he lived on the far west coast of Cornwall, in poverty and with his work overlooked. Since his death, however, his reputation has begun to grow once more – built not on the works of his youth, but more intimate, austere poems addressed to friends living and dead, to his family and to his wife, Nessie.

I’d been searching for years and lead after lead had gone cold: the reading he gave of his poem The Thermal Stair for Westward Television in 1968 which had been erased, or the documentary Harold Pinter had been making about him in 1979 which ended up on the cutting room floor (Pinter considered Graham one of his two literary “masters”, the other being Samuel Beckett). But no luck.

Then one day I came across a letter in the National Library of Scotland, from September 1958, where Graham writes that he had recently appeared on a “Monitor programme” – the seminal BBC arts and culture flagship show of the time – and here I now was, expectant at what it might contain.

Why was I so keen to see this video? I first read Graham’s poetry as an undergraduate – almost two decades ago – and was immediately rapt. In the build up to the centenary of Graham’s birth in 2018, I wanted to let other readers know about this extraordinary, but largely neglected, poet.

Poet among artists

Born in Greenock on Clydeside, Graham left school at 14 and was apprenticed as a draughtsman on the shipyards. His draughtsmanship is evident in the fair copies he would make of his poems, with their fine calligraphy and decorative flourishes.

After leaving Greenock, Graham lived among artists – first in Glasgow, then London, and finally St Ives, which was home to such celebrated figures as sculptor Barbara Hepworth, painter and critic Patrick Heron, abstract painter Roger Hilton, landscape artist Peter Lanyon, and Ben Nicholson, the modernist painter.

Graham was an integral part of this community, but also a distinctive artist in his own right – he produced portraits, landscapes and abstracts on whatever materials came to hand, from hand-painted postcards, to drawings carved in slate, to stained glass.

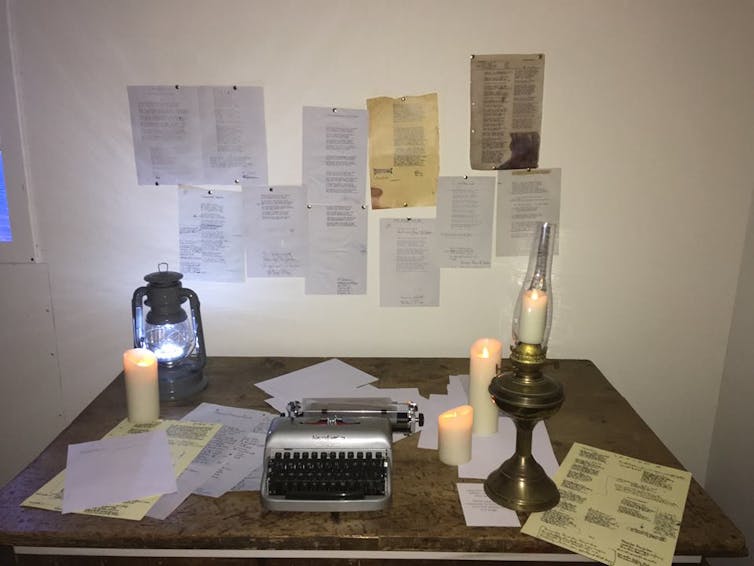

Nicholson once wrote that “Graham’s method of working at his writing seems like my method of working at my painting”. Graham would write out words in a large cursive script – as though they were elements in an abstract painting – and pin them on the wall, as though in an artist’s studio. His notebooks are punctuated by drawings and drafts of poems occasionally include diagrams, as he tried to visualise their overall structure. I don’t know of any other poet who composed in such a visual manner.

This led to a further question: it’s easy to display these manuscripts and drawings in an exhibition, but how could we bring these creative processes to life?

A world of his own

Our solution was to invite our audience into Graham’s creative spaces. We decided to reconstruct his workspace, with his actual writing table (loaned from the Scottish Poetry Library), a replica of his typewriter and recreations of his library and the portrait he painted onto the wall. Meanwhile a soundscape, by sound artist Jamie Perera weaves together many of Graham’s voices, singing and conversing as well as reciting his verse.

Space is an abiding trope in Graham’s work – spaces of communication and of silence, spaces of memory, the physical spaces that surround us.

I say this silence or, better, construct this space

So that somehow something may move across

The caught habits of language to you and me.

We got eyewitness descriptions from friends, made copies of the few photographs that survived, gradually built up a mental image of the interior where he lived. The exhibition became Constructing Spaces, an installation at the South Bank Centre. It will be open until the end of March 2019.

And then, along came that VHS tape. It was a revelation. Entitled: “Why Cornwall?”, it was a short documentary about the artists living in and around St Ives. I’d been expecting Graham to have a brief cameo at best – but no: the feature opens with him, sat at his desk, composing a new poem, with that striking cursive script.

But the video showed us so much more. For instance, that, in their one downstairs room, Graham would sit at his desk, writing through the night, while his wife Nessie was asleep in their single bed: his space for creative work was also a domestic, intimate space. Now we could reproduce the space in minute detail, so that a visitor could step out of the Southbank Centre in 2018 and emerge in a Cornish cottage in 1958 – looking out of the window, not onto the concrete of Waterloo Bridge and the National Theatre, but a video loop of the promontory of Gurnard’s Head.

Graham always believed that the poem ultimately lived in the reader: “The poem is the replying chord to the reader. It is the reader’s involuntary reply,” he wrote in his 20s – and decades later:

The words are mine. The thoughts are all

Yours.

How might we “reply” to Graham today? In our installation, visitors have been inhabiting Graham’s creative processes for themselves. They can contribute to the soundscape with their own voices, type their own poems on the typewriter, produce their own visual works – or just treat it as a place of calm and meditation.

For if making this installation has taught me anything, it is that only as readers respond poetically that a poet is truly brought back to life.