The detention and deportation of Senator Nick Xenophon from Malaysia yesterday are not likely to present problems for Australia—Malaysia relations.

Rather, the Xenophon story is shaped by the domestic political climate in both nations, both of which are preparing for general elections which are likely to be serious contests.

Indeed, Xenophon’s detention at the airport, ostensibly under the Immigration Act because he is a “security risk”, is already being debated by government and opposition coalitions in Malaysia, where an election is imminent but has not yet been called.

Government statements have accused Xenophon of meddling in Malaysia’s political affairs and tarnishing the nation’s good name internationally; while the opposition is calling his deportation a gross abuse of power by the government.

Xenophon had arrived in Malaysia a day ahead of the other members of an unofficial delegation of Australian Members of Parliament, to meet with electoral stakeholders including Mohamed Nazri, a government minister; Anwar Ibrahim, the opposition leader; and Ambiga Sreenivasan, a chairperson of Bersih 2.0 — a coalition of non=-government organisations seeking reforms to Malaysian electoral systems and processes.

Xenophon had travelled on the invitation of Bersih, which maintains that it is not politically affiliated; and he maintains that his purpose was confined to “fact-finding” in one of Australia’s closest neighbours.

The South Australian Senator has visited Malaysia before, including as part of an international delegation of observers invited by Anwar. The role of the delegation, according to a travel report Xenophon has linked to his website, was to observe electoral processes and contribute to a Malaysian discussion about electoral reform.

The Malaysian government’s problem with Xenophon is likely to be that his visits and statements amplify domestic critiques of the way in which elections are conducted in Malaysia.

These critiques are both articulate and, importantly, the Malaysian public is increasingly receptive to them. They target widely-reported electoral problems such as gerrymandering, malapportionment, phantom voters who are registered but cannot be identified, problems with postal voting, and so on.

Public discussion of the electoral system and its weaknesses has dented the ruling coalition’s electoral prestige, and so drawing attention to them in a manner which is both public and international enables the opposition to advance its message.

The ruling Barisan Nasional coalition, which has held power in Malaysia since independence in 1957, lost its constitutionally-significant two-thirds majority in 2008, when election results surprised all observers. This was the first time since 1969 that opposition parties had achieved such a result. Emboldened by that success, the Pakatan Rakyat opposition coalition and Bersih have worked hard to build an international audience for their messages, and these efforts increasingly threaten the government’s electoral security at home.

It is therefore not the material or physical security of Malaysians that Xenophon assists to threaten, but the political security enjoyed by the ruling coalition.

By deporting him, the Malaysian government is likely hoping to shore up its nationalist constituency by preventing an overseas politician—whom they hope to cast as a meddlesome foreigner—from interfering in domestic issues. They will be hoping this move is worth the risk it entails, namely that the public might instead believe the opposition that the government fails to guarantee the political rights of Malaysian and foreign nationals.

In the current political climate, this cannot be guaranteed, and Xenophon himself pointed this out as soon as he landed in Melbourne earlier today.

Xenophon is now safely home in Adelaide, having been fed and treated politely while in the custody of Malaysian immigration officials. Prime Minister Julia Gillard and Foreign Minister Bob Carr have issued statements expressing their disappointment that Xenophon was deported, as has former Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd.

Yet it is unlikely that an ongoing international feud will ensue from whatever diplomatic discussions take place over this matter. After all, the Australian election date has been announced, and it is going to be a long campaign.

Both parties contesting the Australian election are likely to need Malaysia, and the politics of “regional engagement”, to prop up policies aimed at preventing asylum-seekers from arriving in Australia. Many of these asylum-seekers arrive after a period of transit in Malaysia, which will be essential to any regional measures any future Australian government may wish to take. Xenophon is a member of neither of these parties.

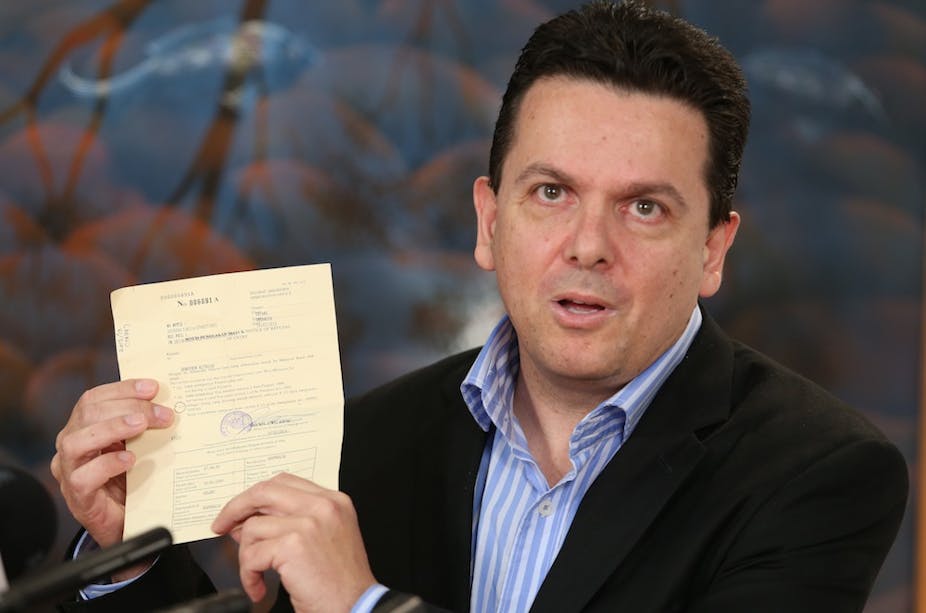

Meanwhile, Xenophon has claimed he is on the same “watchlist” on which the Malaysian authorities are likely to list the names of terrorists. Yet the Malaysian Immigration Department has stated that they had simply treated him as a prohibited migrant, claiming that he participated in activities that are illegal in Malaysia on his last visit in 2012.

Now Xenophon has stated he fears it may be decades before he can return to Malaysia.

Xenophon, too, has an election campaign to fight.