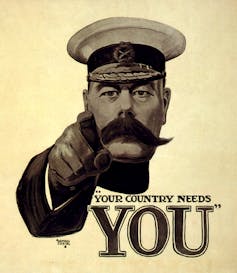

In 1914, the steady gaze and pointing finger of war minister Lord Kitchener urged the men of Britain that they were all needed to protect their country. A century later in January 2019, the British army channelled this message once more in the latest instalment of its controversial campaign “This is Belonging”, which was duly panned for political correctness.

This latest campaign implied that all were needed in uniform, but particularly targeted millennials and Generation Z – youth groups that are all too often mocked and shunned in the media.

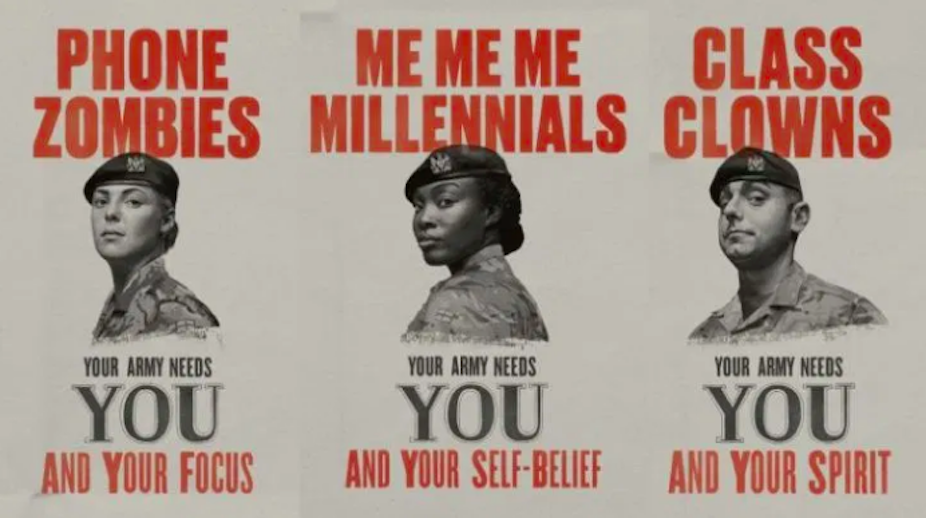

Unlike the previous “Be The Best” campaign – the staple for British army recruitment for many years – and the still-used “Born in … made in the Royal Navy” ads, the recent call for “snowflakes” directly engaged with negative perceptions of modern youth culture. Those considered (by themselves or society) as “snowflakes, selfie addicts, class clowns, binge gamers and phone zombies”, were told they had a place in an army that recognises positive qualities in negative stereotypes.

But the original and the homage campaigns bear three core similarities. First of all, they both promote inclusivity while actually adhering to strict and specific criteria. They also target recruits from the fringes of society, and finally, both have been more infamous than successful.

Same method, same message, same problem

Both campaigns had similar issues. Neither in fact were particularly inclusive. Everyone was needed in 1914 – except of course for the thousands who failed to meet certain specific criteria, such as being over the age of 18 (19 when sent to fight), being taller than 5ft 3", and passing a rigorous medical examination – though the last two stipulations were relaxed in the final years of the war when more men were needed.

A century later, inclusivity now meant reaching out to millennials for the very reasons their generation is so often disdained. So all welcome – except the 92,559 applicants in 2018 who, due to medical and fitness issues, didn’t make the cut to join the 7,441 recruits who were eventually enlisted. Perhaps some of the millennial gamers it looked to attract simply did not possess the core fitness levels required by the army, suggesting the campaign was too narrow in targeting such people in the first place.

After eight consecutive years of recruitment shortage, the 2019 snowflake campaign arrived during a era of questioning the need and purpose of the armed forces. Consistently under target strength since 2000, the rate of trained personnel has been in free-fall. In early 2019, the British Armed forces reported a deficit of 10,000, despite the requirement for personnel decreasing by 27% – down from 190,000 in 2000 to 134,304 today.

The socially aware recruitment campaigns of 2018/19 sought to arrest this decline as part of a £1.6m programme focusing on emotions, individuality and specific millennial “types” such as snowflakes.

Promoting pastoral care (emotional and spiritual support) and the chance to be an individual, the modern military appeared to offer equality and self-expression and value technological dexterity. A century after the end of World War I, the British army was promoting inclusivity to an extent that Kitchener could never have envisaged.

A different tack?

Unashamedly controversial, the snowflake campaign channelled the usual youth-bashing ammunition of raging inter-generational battles. Millennials (born between 1981 and 1996), and Gen Z (born from the mid 1990s onwards), are often denigrated as lacking in conviction, resilience, work ethic, common sense or restraint. Old vs young rhetoric has encouraged media demonisation of what is seen as a hypersensitive, overly indulged youth culture.

In retaliation, these younger generations have criticised the economic decline and political malaise evident in British society since 2000. Recession, environmental crisis, a push toward centre-right politics, Brexit and the rise of populist world leaders have created an anxiety-filled future for them. But with battlelines so clearly drawn, the strength of feeling against the snowflake campaign is unsurprising.

Criticism flew from all sides, with accusations of naivety, diminishing standards and underhand recruitment tactics. Charlotte Cooper of Child Soldiers International slammed the release of the campaign during the “January blues”, saying:

The ‘snowflake’ campaign tried to present a new side to the army, but this advertising brief shows the same old story: young people with the fewest options being mis-sold a one-sided view of military life as the magic ticket to a better life.

Same old story

An overly positive depiction of military life is a tried and tested method of army recruitment. Kitchener’s increasingly desperate attempts to draw in civilians promised everything from full stomachs to sexual adventures. Again falling standards were decried (and then changed to increase recruitment numbers) as Kitchener’s recruits had their pride and commitment called into question.

The British military has always depended on recruiting from the working class. Youth paramilitary organisations dating back to Baden Powell’s early 20th-century scout movement reflected the more accepting and benevolent attitudes to military service that was unthinkable before the Victorian period. No longer seen as “rogues”, soldiering could mean self-reliance, adventure and physical fitness. In the modern forces, enlistees also have access to training, education and development and a sense of purpose and belonging.

Both campaigns enjoyed some success with this message. In 1914 millions came forward to join up. In January 2019, recruitment figures doubled. Yet Kitchener’s success is more myth than reality, as the poster appeared in December 1914 at the tail end of the rush, and the beginning of the slog to conscription in 1916. In early 2019, recruitment numbers certainly increased, but in August 2019 official figures confirmed that the army remains 7,000 personnel short of its target.

A century on, Britain’s armed forces continue to lose trained fighters and struggle to replace them. In desperation – or perhaps inspiration – the old Kitchener method was given another opportunity to galvanise the country’s youth. Numbers may be up, but only time will tell if it can be sustained.