In 1980 I visited the zoo in a major U.S. city and found row after row of bare concrete boxes with jailhouse-style bars occupied by animals from around the world. The animals appeared to be in good physical condition, but many were staring into space or pacing restlessly around the edges of their tiny quarters. It was depressing. I’m not naming the zoo, because you could have seen the same thing at most U.S. zoos in that era.

More recently, visitors to many zoos and aquariums see animals in surroundings that resemble their native habitat, behaving in ways that are typical for their species. What has changed?

In the intervening years, the professional zoo and aquarium community has fundamentally altered the way it views the task of caring for the animals in its collections. Instead of focusing on animal care, the industry is now requiring that zoos meet a higher standard – animal welfare. This is a new metric, and it represents a huge change in how zoos and aquariums qualify for accreditation.

I am a scientist who studies animal behavior, both in captivity and in the wild. This recent development in the zoo world is the result of an evolution in the scientific understanding of animals’ lives and welfare. It also reflects zoos’ and aquariums’ increasing focus on conservation.

From trophy case to conservation message

Since the first animal menageries in ancient Egypt, zoos and aquariums have taken a progression of forms.

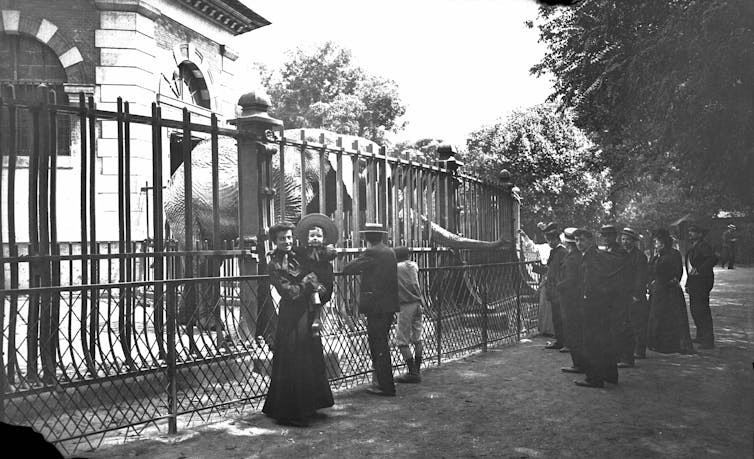

The British Royal Menagerie, which was housed in the Tower of London from the early 13th century until 1835, served as an animated trophy case. In Europe, exotic animal collections were often displayed in garden settings for the amusement of the gentry, and by the late 18th century, for the general public as well. These places often functioned as stationary circuses, sensationalizing the strangeness of animals from afar.

In Victorian England, zoos were recast as edifying entertainments. This was also true in the U.S., where the first zoo opened to the public in Philadelphia in 1874.

Early zoos weren’t very good at keeping animals alive. In the first half of the 20th century, though, zoos began to focus on animals’ physical health. This ushered in the “bathroom” era in zoo design, with an emphasis on surfaces that could be steam-sterilized, such as ceramic tile.

Over the past 50 years, a landscape immersion model of zoo design has risen to prominence, as institutions have evolved into conservation and education organizations. By displaying animals in settings resembling their natural habitat – and setting the scene for visitors to imagine themselves in that habitat – the hope is to instill in visitors who might never see a lion in its element a passion for its preservation.

Changing standards

Accreditation is a mechanism for maintaining and pioneering best practices. Being accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums is the highest level of professional recognition for North American zoos and aquariums. Fewer than 250 out of approximately 2,800 animal exhibitors licensed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture are AZA accredited.

To earn that accreditation, a zoo or aquarium must demonstrate alignment with its mission, a sound business operation and significant activity in the areas of education, conservation and research. But the centerpiece of accreditation is demonstrating quality of life for animals under human care.

For decades, the focus was on practices that correlate with animal health, like absence of illness, successful reproduction and longevity. The AZA has published objective standards for what it means to provide proper care for a tapir, a tiger or a Japanese spider crab – for example, requirements specifying certain amounts of physical space, environmental temperature ranges and cleaning routines. These extensive and detailed standards were devised by working groups of experts in various species from across the zoo and aquarium community and based on the best available scientific evidence.

A recent revision to accreditation standards in 2018, however, supersedes this model in favor of a new goal – that a zoo or aquarium demonstrate it has achieved animal welfare. Not only must animals be healthy, but they should also display behavior typical of their species. Climbers must climb, diggers must dig and runners must run.

Understanding the lives of animals is central

Over the past 60 years, scientific understanding of animals’ cognitive abilities has exploded. A large body of scientific work has shown that a relatively rich or impoverished environment has effects on both brain and behavior. Such awareness has led the zoo and aquarium community to formally embrace a higher standard of care.

Zoo or aquarium personnel can provide such behavioral opportunities only if they know what is normal for that species in the wild. So optimizing animal welfare requires a knowledge base that is both broad and deep. For example, a zoo must understand what is normal behavior for a pygmy marmoset before it can know what behavioral opportunities to provide.

Many zoos and aquariums house hundreds of animal species. Each species exists because it occupies a unique niche in the ecosystem, so the conditions that produce ideal welfare for one species may not be the same as those for a different species.

Developing welfare standards for the wide diversity of zoo species will take time and quite a bit of research. Although AZA-accredited zoos and aquariums contribute over $200 million per year to research in over 100 countries around the world, the need for conservation research always far outstrips the available funding.

How old is an eastern black rhinoceros before it begins to go on adventures away from its mother? If a flamingo chick has a medical issue that is successfully resolved, how can keepers tell if its development has been affected? How can keepers evaluate whether items introduced into the enclosure of a troop of Japanese macaque monkeys, intended to enrich their environment, are actually serving that purpose? Knowing the answers to these questions, and a multitude of other similar ones, will help the zoo community truly optimize the welfare of animals under their care.

Another major factor behind the AZA’s new standard is its role in species conservation. Captive animals typically outlive their wild counterparts. Zoos and aquariums are the figurative lifeboat for an increasing number of species that are extinct in the wild. Simply keeping an animal alive is now no longer enough. Zoo-based efforts to save endangered species will succeed only if understanding of the animals’ lives is fully integrated with husbandry standards.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]