When some women won the right to vote in Britain in February 1918, the question arose as to whether women could now stand in parliamentary elections. Nine months later, the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act was passed on November 21 1918, enabling women over the age 21 to become MPs.

A century on, the UK parliament now has 208 women MPs. But what was it like for the first women in the House of Commons 100 years ago?

Only women over the age of 30 who met a property qualification were granted the vote in 1918, therefore there are numerous examples of women standing for parliament when they could not vote themselves.

The path to entering parliament was not an easy one for women; political parties prioritised male candidates and finances hindered many women from standing. In all, 17 women stood in the 1918 general election across the political spectrum, but only one woman was successful, Constance Markievicz. As she stood for Sinn Féin, she refused to take her seat over the issue of Irish independence.

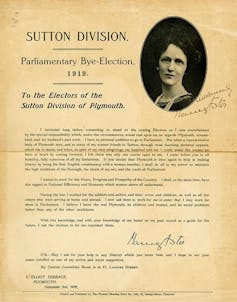

It wasn’t until the following year that the first woman MP to take her seat was elected when Nancy Astor was elected in a Plymouth by-election in 1919 for the Conservative Party. She was persuaded to stand by her husband, who previously held the seat, when he was elevated to the House of Lords following the death of his father. Women MPs inheriting their seats from their husbands became a common pattern in the interwar period. For Astor, being the only woman MP was an isolating experience. In 1923, she remarked: “Pioneers may be picturesque figures, but they are often rather lonely ones.”

A masculine space

Parliament was, and arguably still is, an inherently masculine space. The corridors were lined with paintings of white male politicians, the bars and smoking rooms remained closed to women, and the female restroom was a quarter of a mile walk from the debating chamber. Outside of the chamber, Astor confined herself to the Ladies Members Room. As more women entered parliament, they shared this space. It was nicknamed the “tomb” as it was cramped and poorly furnished.

Despite Astor’s success, most MPs remained adamant that parliament was no place for women. Winston Churchill, although a personal friend of the Astors who dined regularly at their country house, refused to speak to Astor in parliament. He revealed later on in life, that by ignoring her, he and other MPs “hoped to freeze her out.”

In 1921, Astor was joined by the Liberal Margaret Wintringham following her success in a by-election in Louth. She also inherited her seat from her husband who had died while in office. Despite being in different parties, Astor and Wintringham became great friends, working together on issues related to women and children. In her maiden speech, Wintringham spoke during a debate on the economy and said she felt “rather like a new girl at school”. Women MPs continued to enter parliament in slow numbers. By 1929 there were only 14 women MPs, despite 69 women standing in the 1929 general election.

Appearances scrutinised

The press became fixated on the appearance of early women MPs. Astor insisted on wearing simple clothing as she wanted her politics to be remarked on and not her outfits. Other women MPs adopted this “parliamentary uniform”, although there were some exceptions.

Ellen Wilkinson, Labour MP for Middlesborough, elected in 1924, refused to conform to Astor’s dress code. Nicknamed “Red Ellen” for her socialist views and fiery red hair, she had a colourful sense of fashion. When criticised for this in the press, she remarked: “Can’t a woman do her work just as well in a dress of bright colour?”

Jennie Lee, the Labour MP for North Lanarkshire was elected in a by-election in March 1929, aged 24. At the time, she could not vote herself, yet still became the youngest MP in the Commons. Lee created chaos when she wore an emerald green dress into parliament. One press report of the occasion recounted:

The dress, which was of a clinging variety and of ankle length… took the Speaker’s breath away … She swept to her place … with all the assurance of a Bond-street mannequin.

Women MPs today continue to face sexism, bullying and comments on their appearance, and in the digital age, receive frequent abuse online. While Westminster now has a nursery and considerably more female toilets, its archaic traditions still dominate.

A century later, the UK still doesn’t have equal representation in parliament, and only 32% of MPs are women. While campaigns and policies such as 50:50 Parliament, #AskHerToStand and Labour’s all women short lists are increasing the number of women MPs, a recent report from the Fawcett Society concluded that: “Women still experience multiple barriers to being selected as candidates simply because they are women.”

The first women MPs were pioneering and paved the way for future generations. A century later, the spotlight is on Westminster as the fight continues for equal representation and the challenge against the notion of parliament as “the old boys club”.