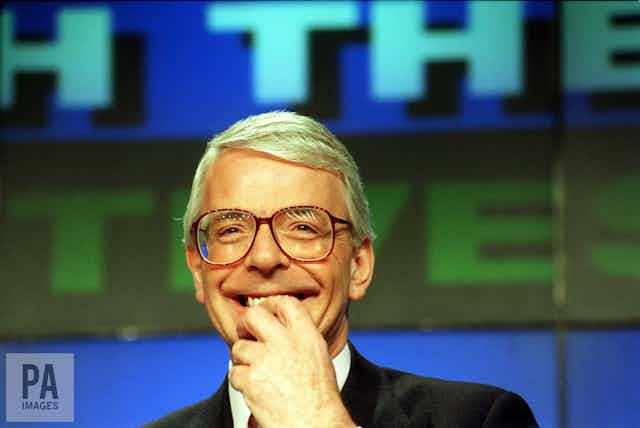

Few would say that John Major was among the most distinguished of prime ministers, sandwiched as he was between the much more dramatic premierships and dominant personalities of Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair. His time in Downing Street ended 20 years ago, when Major suffered a crushing electoral defeat at the hands of Blair’s New Labour.

The cabinet and parliamentary Conservative party had become so divided that Major felt compelled to resign the leadership two years earlier in 1995. While he was then re-elected as leader, the divisions were deep, making defeat in 1997 almost inevitable.

In our book on Major, we seek to offer a more balanced perspective.

All prime ministers operate within a context which can provide both opportunities and difficulties, and those who look weak often face the most difficult contexts. Such was the case with Major.

The nature of Major’s accession to power created much of the difficulty. Thatcher had not lost an election. She had even (technically) won the leadership contest against Michael Heseltine in 1990, just not by enough votes to win under the party’s rules. The subsequent cabinet coup led to her decision to stand down.

Unable to identify a true believer to take over, she settled on Major, who she felt was the closest to it. He soon proved to be his own man and Thatcher felt unable to relinquish power, becoming a constant thorn in his side. She described herself as his backseat driver.

Early challenges in office

For the first two years in Downing Street, Major lacked a personal mandate. Then came 1992, the defining year of his premiership. In May, he won the Tories an unprecedented fourth term of office, largely as a result of his own campaigning tactics – most famously, his decision to stand on a soapbox in Luton to campaign.

Then, in September 1992, the UK was forced out of Europe’s Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) for failing to meet its requirements. Major had been the chancellor who had taken Britain into the ERM, despite Thatcher’s caution towards the policy. Its failure was therefore his failure. The Tories had won the election largely on the grounds that the electorate believed that they, and not Labour, could be trusted to manage the economy. Now, their reputation for economic competence was shattered.

The polls immediately changed and Labour – now under the leadership of John Smith – moved ahead. That lead was only boosted by the election of Tony Blair upon Smith’s death in 1994. Rarely has one event proven so decisive. Ironically, the economy picked up once Britain was out of the ERM but Major never got the credit.

Beginnings of Brexit

Under normal circumstances, the majority of 21 achieved in 1992 would have been sufficient for a full parliamentary term, but these were not normal times. In the final stages of Thatcher’s premiership, the Conservatives had become much more eurosceptic – and the ERM debacle only encouraged Major’s opponents within the party to believe that the European project was doomed.

Major had been negotiating the Maastricht Treaty, and had got opt-outs on the single currency and social chapter. He believed this would be enough to win over the doubters on his backbenches. Yet he failed to anticipate the level of opposition, whipped up by Thatcher and her key aide Norman Tebbit in the House of Lords. For months, the saga dragged on and the parliamentary majority was non-existent on this issue. Eventually, as Major intended, the Maastricht Treaty was ratified by parliament in 1993 – but only once he had lost much of his political capital.

The overriding objective of Major’s premiership was to keep his bitterly divided party together. Despite all of the challenges, this was achieved.

Unsung successes

There were numerous other policy developments. The hated community charge (poll tax) was quickly abolished. Privatisation continued, most controversially and least successfully British Rail. Key reforms were introduced in the NHS and education, and jobseekers’ allowance was created in 1996. Perhaps the most popular domestic policy measure was the National Lottery, with millions raised for good causes in sport and the arts. Although Blair was to take most of the credit for the Northern Ireland peace process, John Major had done most of the heavy lifting and deserved more recognition.

Conscious that likely electoral defeat was looming, in 1997 Major pledged to save, as he saw it, the Union. New Labour advocated devolution for Scotland and Wales, believing it would halt the rise of nationalism. Major argued that it was a dangerous policy that would only fuel nationalist sentiment.

He may well still be proven correct on this issue, especially in Scotland where a second independence referendum looms.

Once the result was declared, Major said that he was off to watch cricket at the Oval. He has remained dignified since leaving Downing Street. To say he is a successful ex-prime minister would seem like a backhanded compliment, but compared to how Heath treated Thatcher or how she treated Major, or the very low regard in which Blair is now held by many, this is quite an achievement in its own right.

Many of the contributors to our book conclude that Major was an honourable and decent man who served his country with good intentions. Perhaps this is not too bad an epitaph.