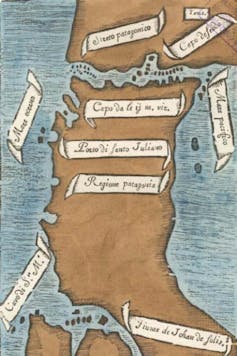

Five hundred years ago, on March 31 1520, the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan began a sojourn in a part of South America that has been known as Patagonia ever since. Magellan’s five-month long overwinter in a natural harbour that has become known as Puerto San Julián was part of the first circumnavigation of the globe.

It was in this area, which spans Argentina and Chile today, that Europeans first made contact with local indigenous peoples. Magellan’s chronicler, Antonio Pigafetta, described them as giants. Magellan himself coined the fantasy-inspired term “Patagonians”.

With its allegedly colossal inhabitants and unexplored riches, Patagonia captured the European imagination. Magellan’s first journey led other European explorers to try and reach the Pacific via the route henceforth known as the Strait of Magellan.

Successive chroniclers added layers of legend and fabrication to the European imagination about the indigenous peoples – the Tehuelche, Mapuche, Williche, Kawésqar, Yagan, Selk'nam and Haush, among others – who inhabited the region.

European place names cropped up on European maps as white explorers “discovered” new places. Indigenous peoples were progressively chased from their territories across the region, raped and murdered to make space for so-called “civilisation”.

The process intensified after Argentina and Chile gained independence from Spain in the first decades of the 19th century. While Patagonia was meant to be under their jurisdiction, in reality the local indigenous groups retained control of the region.

But this changed from the late 19th century onwards under aggressive state land grabs. Chile’s “Pacification of Araucanía” from 1861–83 and Argentina’s “Conquest of the Desert” from 1879–85 pushed the internal frontiers southward. The euphemistic names of these military campaigns cynically masked their violence, and the goal to open up the land for ranching and settlement by white settlers, preferably from Europe.

Violence and relocation

In the aftermath of state occupation, indigenous peoples were decimated and displaced, sometimes confined into reservations or exploited as cheap or semi-slave labour. Some became farmhands in largely British-owned estancias – massive ranches. Others were transferred to the north to harvest cotton, vine or sugar cane, or build the railroads. They suffered forced relocation, detention in concentration camps and the removal of their children – policies that deeply disrupted their social and political organisation.

The indigenous reservations that were created in Southern Patagonia after the military campaigns were guarded by the state and the church. Those who survived the gold rush in the Tierra del Fuego archipelago were absorbed into missions by Anglicans or the Catholic Salesian order who sought to redeem them from their alleged “savage” state.

Those affected by these violent policies often hid their indigenous origins and refrained from passing community memories and knowledge onto younger generations. Since they did not speak their parents’ native languages, they were not considered indigenous but rather as “descendants”.

Relying on racial ideologies, eugenics-influenced scientific studies in the 1930s focused on what they called “the last pure indians” and forecast the imminent extinction of Patagonian indigenous peoples. Closing the circle, subsequent assimilationist policies encouraged indigenous people to relocate from rural into urban areas, where they became an invisible part of the lower classes.

In the 1980s, indigenous peoples in Patagonia were officially pronounced extinct with the exception of the Mapuche. Their survival gave rise to widespread accusations that they were were not authentic indigenous peoples – something the Mapuche challenge.

Controversial anniversaries

Debates around the commemoration in 1992 of the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s “discovery” of America in 1492 created winds of change. Contending that there was “nothing to celebrate”, indigenous campaigning across the American continent succeeded in drawing public attention to the many misdeeds of the conquistadors and the ongoing consequences of the genocide.

Pressure by indigenous groups to get countries to recognise the bloody legacy of European conquest and colonialism has prompted various levels of indigenous recognition, reparations and assurances of rights. Argentina and Chile have both ratified the International Labour Organization’s Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention and voted in favour of the UN’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. But implementation is a different matter.

Read more: Why more places are abandoning Columbus Day in favor of Indigenous Peoples Day

Whether acknowledged by the state or not, indigenous reemergence processes across the Americas are unstoppable. While the Tehuelche and Selk'nam challenge claims that they are extinct, the Mapuche have accused the governments of Chile and Argentina of genocide.

Families, communities and indigenous organisations are linking past and present by piecing together their fragmented and painful memories, in dialogue with researchers, and sometimes using digital technologies, such as apps.

Nothing to celebrate

Indigenous peoples are fighting resource extraction in the region which has a direct impact on their territories, bodies and spirits. They are also challenging heritage initiatives which appropriate their past and knowledge, such as the use of indigenous culture in provincial government promotion materials. And they continue to demand compliance with their often infringed rights to consultation and consent for activities on their traditional lands.

Legislation which recognises indigenous sovereignty and territorial rights has meant some communities are now at the forefront of protecting biodiversity in the region. However, this has also made them a prime target of attacks.

Reacting to the official celebrations of Magellan’s arrival in 1520 which are taking place around the world, indigenous people have expressed great sadness over these dark 500 years. Despite the persistence of European-centred versions of history, there is a growing awareness that – as with the Columbus anniversary – neither the bloodshed and plunder heralded by Magellan, nor the endurance of colonial legacies, are any cause for celebration.