Tanzanians will head to the polls on 28 October in which the incumbent, John Magufuli, faces a determined opposition. Elected to a first term in 2015, Magufuli’s time in office has lived up to his nickname tinga tinga, Kiswahili for “the bulldozer”. He has been applauded by some for advancing a series of major developmental projects. Others have denounced him for his arguably more autocratic, repressive rule

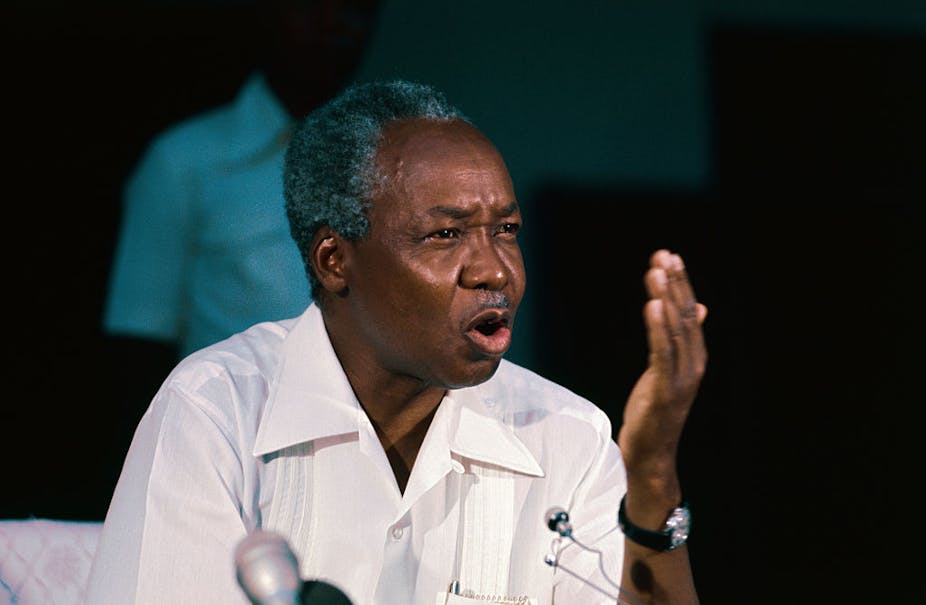

Magufuli leads Chama Cha Mapinduzi, one of the longest serving ruling parties in Africa. It is also the party of Tanzania’s socialist founding father, Julius Nyerere, who looms large over the country’s politics more than 20 years after his death.

As the French anthropologist Marie-Aude Fouéré has noted, Nyerere remains

a political metaphor for debating and acting upon the present.

Magufuli has repeatedly played up the similarities between himself and Nyerere. His supporters cite his attacks on corruption among the ruling political class and his enthusiasm for completing infrastructural projects as evidence that he is the “Nyerere of our time”.

Others are less reverent. They include Tundu Lissu, the presidential candidate for the main opposition party, Chadema. His family was forcibly relocated under Nyerere’s villagisation scheme of the 1970s. He brands Nyerere an autocrat who built an “imperial presidency”.

There is ample evidence of the ruling party’s tightening grip on power under Magufuli. In the lead up to the 2020 election, opposition rallies have been blocked. The press has been muzzled, and prominent opposition politicians have been violently attacked.

In August, the Magufuli-controlled National Electoral Commission’s registration of candidates was marked by irregularities. Many opposition politicians were disqualified from contesting in October.

Lissu himself only returned from exile in July after surviving an assassination attempt in 2017. For him, Magufuli’s brand of authoritarianism has its roots in the Nyerere era.

As these contrasting depictions of Nyerere attest, his ideas and legacy remain objects of debate in contemporary politics, especially in an election year.

In my research, I explore the political history of the Nyerere era. I examine his socialist project through the prism of Tanzania’s first and most prestigious national university, the University of Dar es Salaam.

Charting the rise and fall of leftist student activism at the university throughout the 1970s and 1980s allows us to better understand the aspirations of Nyerere’s socialist project and its ultimate limits and legacy.

The Arusha Declaration

African universities were key to processes of decolonising and developing post-colonial states at independence. The young nations relied on them to produce new professional classes and state bureaucrats. Given their national importance, African presidents were commonly appointed as chancellors.

As both president and chancellor of the university, Nyerere’s idea was that it should produce “servants” committed to building the Tanzanian nation. As he put it, its role was not to

build sky-scrapers here at the university so that a few very fortunate individuals can develop their own minds and live in comfort. We tax the people to build these places only so that young men and women may become efficient servants to them.

It was partly for this reason that he was deeply disappointed by the student protests of late 1966. In October of that year, students marched on the streets of Dar es Salaam against mandatory induction into the government-run National Service scheme. They were expected to spend their first two years after graduation working in nation-building programmes on 40% of their normal stipend.

Worried that the university was producing a generation of self-centred elitists, Nyerere decided to take dramatic measures. All the protesters were expelled from the university. To demonstrate the value of personal sacrifice for the Tanzanian nation, he cut his own salary by 20%.

In the aftermath of these protests, in February 1967, Nyerere released the Arusha Declaration. This explicitly committed his government to socialist policies, including nationalisation and rural collectivisation.

Soon after, he vowed to transform the university into a socialist institution. The ruling party created a youth wing branch on campus. A general course on the political economy of development was made mandatory for all students.

These reforms and the Arusha Declaration inspired the emergence of a small, but vocal group of leftist students on campus. These notably included the Yoweri Museveni-led University Students’ African Revolutionary Front. It started a student journal, organised public lectures and teach-ins, and raised money for African liberation movements.

But, over time, the government became increasingly concerned by the prominence and independence of these leftist student groups. In the 1970s and 1980s, student politics came to be marked by an unmistakable irony: in the years following the supposed socialist transformation, leftist student activism at the university actually declined.

This is largely because the government exercised increasing control over university activities. Ruling party loyalists were appointed to high-ranking positions in the university administration. Following public displays of student dissent in 1970 and 1978, independent student bodies were dissolved.

Slowly, but surely, the university was brought more squarely under the control of the ruling party.

Political order over independence

This approach to public dissent was the rule rather the exception in Nyerere’s Tanzania. Trade unions, rural development collectives and party youth organisations were banned or brought under party control if they displayed too much independence. Faced with increasing economic challenges, Nyerere regularly felt the need to prioritise political order and obedience over desires for mass-driven socialist transformation.

But to label Nyerere as merely an authoritarian, as Lissu suggests, is to gloss over the complexity of his years in power. As chancellor, he distinguished himself from the vast majority of his African counterparts. All too often, he sought to win students over through argument, rather than coercion.

His legitimacy among the student community did not rest on patronage or intimidation. Rather, many were committed to his socialist ideology, which he called ujamaa. It emphasised equality, self-reliance, national unity, and African liberation.

They respected the fact that Nyerere consistently communicated these ideas to them directly. His frequent visits and candid exchanges with students on campus helped maintain his popularity among them.

This legitimacy is reflected in the fact that on the rare occasions when students took to the streets to protest post-1966, it was never against Nyerere’s socialist project. Rather, it was to rail over its perceived betrayal by the political elite.

Examining Nyerere’s legacy through this prism, therefore, complicates characterisations of his domestic legacy as singularly autocratic. It is true that his regime did stifle leftist student activism. But many students believed in and were inspired by his socialist ideals and his sense of political morality.

Nyerere’s legacy still looms large over the country’s politics, and not just within Chama Cha Mapinduzi. The upstart opposition party, Alliance for Change and Transparency has declared its desire to revive and update the Arusha Declaration if elected to power in October. They explicitly commit themselves to

building a socialist society with equality as its basic principle.

The resonance of this message with young Tanzanians suggests Nyerere’s legacy is far more complex than either Magufuli or Lissu recognise.

For all his shortcomings, Nyerere’s ideas continue to inspire Tanzanians fighting for a more equal and democratic future.