Last week the New South Wales Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) began investigating a political donation of A$18,000 made by Nathan Tinkler’s Buildev corporation.

The 2010 donation helped fast-track approval for 1,400 medium-density homes in Sydney’s western suburb of North Richmond. Local residents have long been opposed to the development; they claim it will choke already congested roads in and out of the area. But recent news reports have missed a crucial aspect of the development proposal: it will obliterate a site of national heritage significance.

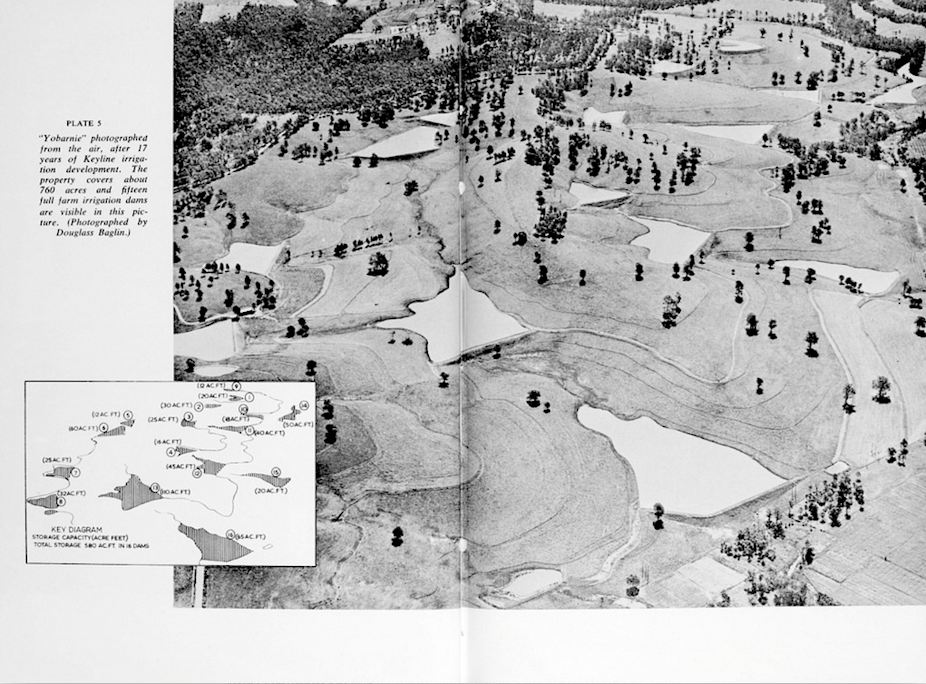

The proposed housing development is marketed as Redbank, but to proponents of sustainable agriculture, the 180-hectare property is more readily recognisable under its former name, Yobarnie.

From the mid-1940s, Yobarnie is where Australian inventor P.A. Yeomans carried out the world’s first experiments in Keyline Design. He trialled dams, water channels and ploughing techniques to retain water in the landscape for as long as possible. Yeomans’ work is widely acknowledged as one of the major influences on permaculture, an ecological design system which began in Australia in the 1970s.

Prior to purchasing the property, Yeomans worked as an engineer with particular expertise in the supply and drainage of water on mine sites. The acquisition of Yobarnie marked the beginning of his application of these hydrology skills to agriculture.

He began to experiment with harvesting rainwater via a set of interlinking dams. He used gravity to irrigate the entire farm. After much trial and error, Yeomans finally developed Keyline Design, a method of “reading” the landscape. He allowed the land itself to determine the best placement of roads, buildings, paddocks and dams.

Rather than imposing a rectilinear grid, the land’s own contours were decisive factors in a whole-system approach to farm design. The result was a strong increase in soil fertility and water retention without the need for artificial fertilisers.

The importance of Yobarnie was acknowledged in 2013, with the property added to the NSW State Heritage Register. Yobarnie was listed for its historical, associative, aesthetic and social significance, as well as for its research potential.

It was Buildev’s medium-density housing proposal which prompted a local residents action group to begin assembling a case for the listing. Although the heritage order looks good on paper, its impact on the ground is minor, calling for some modifications in road layout and the installation of interpretive panels. Ironically, the developer of Redbank has since moved to capitalise on the heritage listing, with Yobarnie’s illustrious past now incorporated into its marketing material.

Local opponents to the Redbank development have seized on the ICAC investigation to bring attention to the site’s poor infrastructure design. There is only one way in and out via car: the Kurrajong Road Bridge over the Hawkesbury River, already subject to long peak-hour delays. An alternative access point has been proposed, joining Grose River Road to Springwood Road, but this requires the building of a major new bridge across a favorite local swimming spot at Navua Reserve.

In 1971, P.A. Yeomans published The City Forest. The book was a passionate appeal for adaptation in the face of looming ecological crisis, and a technical manual for how this might be achieved. He scaled up his Keyline farm design methods to tackle the complex problem of urban planning.

The same principles applied: analyse the situation, allow the land’s contours to determine placement of key elements, and set up water flows and access points so the system functions in a self-sustaining manner.

Of course, these suggestions seem hopelessly utopian in the face of Sydney’s property market, even without the spectre of corruption thrown in for good measure. But it does seem particularly frustrating that the proposed development on Yobarnie, where it all began, is now suffering from elementary design faults which could be resolved by consulting Yeomans’ own teachings.

Redbank’s current masterplan follows the standard medium-density outer-suburban model: single story houses on individually fenced plots of land accessed by private car. But a re-imagined Redbank-Yobarnie could be a model for the sustainable housing of the future.

It could easily generate its own power. Water for residents could be provided via the existing network of Keyline dams. Organic waste could be composted on-site, as could human manure, greatly reducing the impact on centralised rubbish dumps and sewerage systems. The resulting soil could be used for integrated local market gardens, a crucial contribution to food production in the face of suburban sprawl. The neighbourhood could include a sustainable design study centre, attracting visitors from around the world.

A radical re-design of this sort would be a fitting tribute to Yeomans’ heritage. It would put Hawkesbury Council on the map, bringing in tourist dollars and creating opportunities for strategic positioning at the beginning of the post-carbon era.

This week Mark Regent and Bart Bassett will face questions at ICAC about the Redbank development. As they do so, the current pause to the development offers the chance to consider a better way to design new peri-urban neighbourhoods.