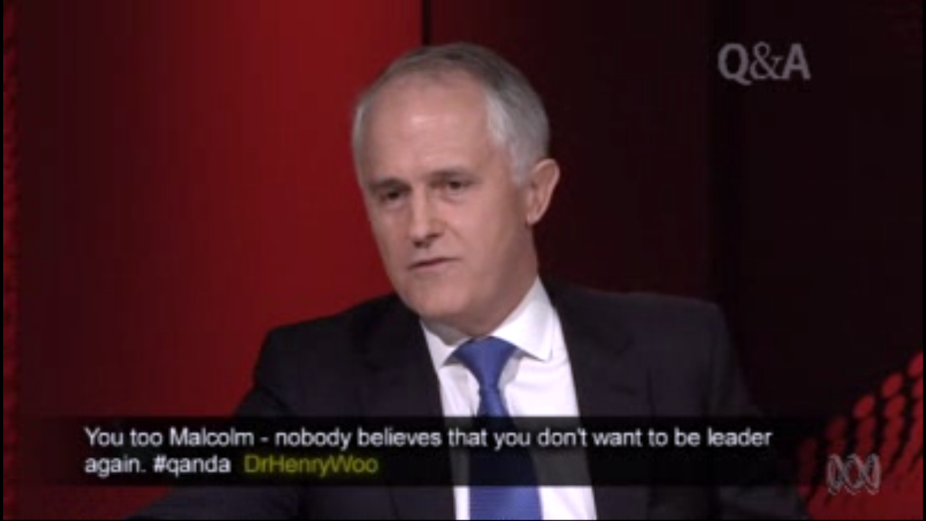

Kevin Rudd and Malcolm Turnbull’s appearances on Q&A last night were always going to make a splash.

High-profile media appearances by Rudd and Turnbull inevitably prompt speculation among the media and the general public over the possibility of a leadership challenge from either former leader. The audience members wearing Kevin07 t-shirts attested to Rudd’s enduring popularity in some quarters.

The argument for change is twofold. First, that Rudd and Turnbull are more talented political leaders than Julia Gillard and Tony Abbott. Second, that the standard of political debate in Australia would be higher if Rudd and Turnbull returned to their old jobs of Prime Minister and Opposition Leader.

Last night’s episode of Q&A provided little actual fodder for commentators keen to fuel talk of leadership challenges. But that didn’t stop news.com.au running a poll this morning on the preferred leaders for both parties. Nor did it stop people taking to Twitter to demand Rudd and Turnbull either form their own, new party or be reinstated as leaders of their current ones.

But on the show, Rudd and Turnbull were circumspect in their remarks, saying little that could reasonably be interpreted as damaging their own party. This is not surprising.

While it is impossible to predict for certain what will happen in the lead-up to the next election, the odds are stacked against Rudd returning to the Labor leadership. This is partly because recent polls have been more positive for the Gillard government. And it cannot be forgotten that Rudd lost the Labor leadership ballot earlier this year, securing only 31 votes compared to Julia Gillard’s 71.

For Malcolm Turnbull, too, it will be difficult to regain the leadership prior to the next election. Although the Coalition’s lead in the polls has narrowed over the last few months and Tony Abbott’s approval ratings have fallen, it is still ahead of the government. Even if a change in leadership were to occur, Malcolm Turnbull’s views on climate change policy are likely to be a major obstacle to his leadership aspirations. His views clash with the views of many of his colleagues, and given the centrality of climate change to the opposition’s case against the government, the odds also seem stacked against Turnbull’s reinstatement as Opposition Leader before the next election.

Regardless of whether it is likely to happen, the return of Rudd and Turnbull would also be unlikely to herald a significantly more harmonious and deliberative approach to politics in Australia.

While political debate has been characterised by a high degree of hostility since 2010, party leadership is not the sole reason for this. The fact the Gillard government is a minority government is particularly important, because it means its hold on power is more precarious than it normally would be. This explains, in part, why the allegations surrounding backbench MP Craig Thomson were pursued so relentlessly by the opposition and received so much media attention.

More generally, the media environment in Australia makes in-depth debate over policy issues difficult. The over-the-top rhetoric of talkback radio hosts is certainly part of the problem, but so is the mainstream media’s focus on “horse race politics” and its tendency to overplay relatively small movements in opinion polls over short periods of time.

The intensification of media coverage is also a factor. The rapid speed with which news is communicated and the host of panel shows, such as Q&A, discussing the latest political developments mean that politicians are under greater scrutiny than ever before. In this environment, it is logical for political leaders to respond by trying to control their interactions with the media as much as possible, leading to an emphasis on spin and media management.

It is also important to remember that we have had recent experience of Rudd and Turnbull as Prime Minister and Opposition Leader. While public debate during this period may have been, on the whole, better than it is now, it was hardly a golden age of sophisticated and deliberative political discussion.

In fact, Kevin Rudd was frequently criticised for focusing too much on spin and winning the daily news cycle instead of pursuing the big issues. Malcolm Turnbull also ran into difficulties in the “Utegate” affair, which was hardly characteristic of constructive, high-level public debate.

Finally, it is important to bear in mind that for all the hostility of the past two and a half years, the current parliament has been able to pass significant pieces of legislation, including the carbon price. In evaluating this time, it is important to take into account legislative outcomes, as well as political debate.

None of this is meant to deny that Australian politics has been particularly hostile since 2010, or that party leadership can make a difference. It seems unlikely, for instance, that Malcolm Turnbull would have used the sort of sexist language that Tony Abbott has adopted against Julia Gillard.

The point, rather, is that all political leaders face challenges in the current political environment. This makes it difficult for them to engage in the sort of high-quality, sophisticated debate over public policy many of us would like to see. And it means we need to be more realistic about the likely consequences a change in leadership would have for the current state of political debate.