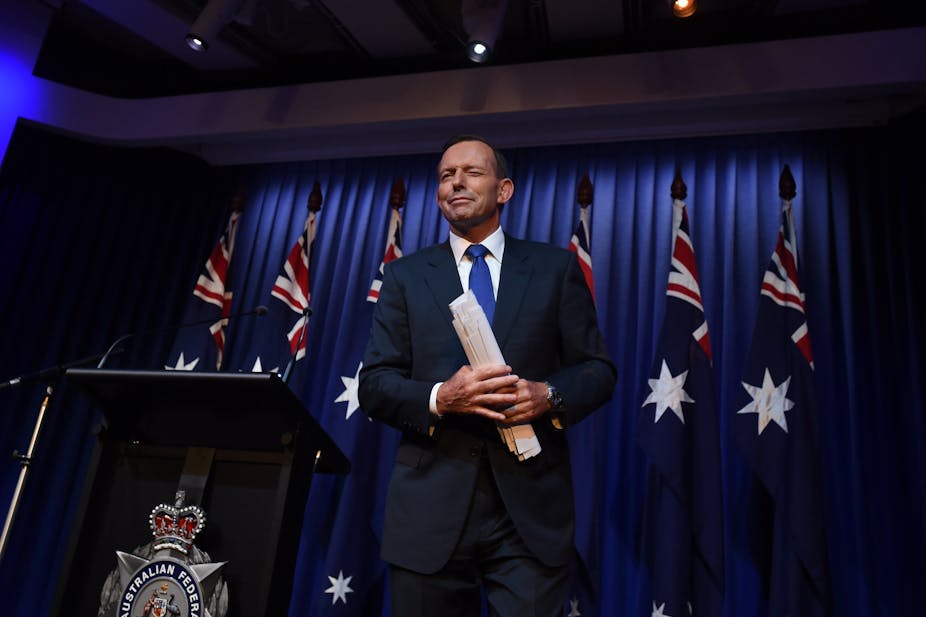

Prime Minister Tony Abbott deserves the benefit of the doubt that his intentions to further strengthen Australia’s national security are good, well-planned, and, most importantly, fully justified.

Aside from drawing on national security as a trump card when political popularity may be faltering, the government does seem genuine in wanting a safer Australia. But despite its intentions, the changes to Australia’s security arrangements announced by Abbott on Monday are unlikely to add to existing capabilities.

The additional measures, which include creating a national security co-ordinator, tightening immigration, cutting welfare payments, and further strengthening legislative powers, are unlikely to make Australia more secure. What they are likely to achieve is the erosion of civil liberties by paying lip service to the underlying causes of what drives people to seek out terrorist groups in the first place.

As such, the new measures will not only have very little impact on Australia’s security, but they also have the potential to exacerbate the underlying causes of violent extremism and further damage Australia’s social cohesion.

What informed the government’s changes?

Much of Abbott’s announcement is based on the findings from the Martin Place siege inquiry and a separate review of Australia’s national security architecture. It is always a healthy practice to review response procedures and arrangements after such a tragic incident like the Martin Place siege. The NSW Police and Emergency Services did a commendable job and the Martin Place review doesn’t challenge this.

The government is also right in declaring that Australia is at a new and long-term state of heightened threat. This has emerged from acts or plots of lone wolf terrorism, the ongoing concern regarding returning foreign fighters and the most recent threat from terrorist groups targeting Western shopping centres.

But given this concerning security situation, Abbott’s latest announcement falls short.

To suggest that Man Haron Monis, the sole perpetrator of the Sydney siege, represents a typical profile of the new lone wolf terrorist threat that Australia is now facing is erroneous. The government should not be making changes to national security based on one man’s mental health issues.

There is no doubt that Monis was screaming out for attention. His criminal and serial pest activities spanned almost 18 years. But despite Islamic State (IS) praising him for his actions, Monis had no clear affiliation to any terrorist group. He also had no religious credibility among the Muslim community – he was an outcast. Nevertheless, he was someone who probably should have been taken more seriously and dealt with by authorities much earlier.

Monis was assessed by ASIO in early December 2014 but “fell well outside the threshold” to be deemed a high-priority counter-terrorism target. However, there may have been opportunities for intervention with Monis, particularly to deal more closely with his state of mental health and his desire for attention.

There is still very little information from the Monis case that tells us the reasons for his decision to commit an act of terrorism. While Monis is different from other offenders accused of planning more recent lone wolf acts, there is still much to be done to try to intervene and deal with individuals who are recognised as vulnerable to radicalisation or who are well down the path of violent extremism.

One very positive aspect of Abbott’s announcement is that the attorney-general’s department is planning to develop so-called “softer” initiatives to counter violent extremism (CVE). These initiatives are likely to involve non-government agencies traditionally outside sensitive national security arrangements.

The government will need to expedite work in this area so it can adequately support communities and frontline service providers to both recognise signs that someone may be radicalising and to adopt strategies to intervene and manage their cases. As part of the broader CVE program, Attorney-General George Brandis announced that the government will also create a body to monitor social media and take down terrorist propaganda.

The implications of Abbott’s proposals

While the new initiatives to counter violent extremism are commendable and will hopefully lead to a reduction in terrorism, the overall problem is made more complex by the direction the government seems to be heading on counter-terrorism more broadly. Australia’s increasing hardline on national security is counter-productive.

For instance, in earlier statements, Abbott didn’t see much value in intervention. Referring to foreign fighters, he said last September that:

Unfortunately, terrorists don’t reform just because they’ve returned home, as the experience with Australians returning from fighting with the Taliban shows.

Abbott’s message “to all Australians who fight with terrorist groups is that you will be arrested, prosecuted and jailed for a very long time”.

Further, Abbott’s proposal on Monday to strip suspected IS supporters of their citizenship or dual citizenship may be problematic in the long run. The threat of de-naturalisation from Australia and the risk of becoming stateless may reinforce IS’s notion of being a religious state outside official international acknowledgement.

Telling people they are no longer Australian also confirms their feeling of disenfranchisement and rejection of so-called Australian values. Such actions do not play well with individuals already disillusioned with Australian society.

The government is also verging towards “the explicit removal of the presumption of innocence” – in the words of controversial group Hizb ut-Tahrir – by criminalising peaceful political activism in cracking down on Islamic movements. Australia’s grand mufti, Ibrahim Abu Mohammed, had previously criticised the government’s moves in this area. He said it would be a “political mistake” to ban Hizb ut-Tahrir.

To be effective, there are also underlying socioeconomic issues that will also need to be addressed in parallel with any national security and counter violent extremism strategy. Australia is currently at its highest youth unemployment rate since 1998. Many who migrate to Australia struggle to gain acceptance, find employment or other critical opportunities for day-to-day survival. The end result is that the international forces driving terrorist ideology are having a greater appeal than living in, or valuing, Australian society.

Australia’s response to terrorism must not be rooted in short-term political gains, but in a larger strategy that takes into account the problems leading to social disaffection and addresses them simultaneously with the tougher national security posture. Our response to terrorism must be measured, focused, practical and compassionate.