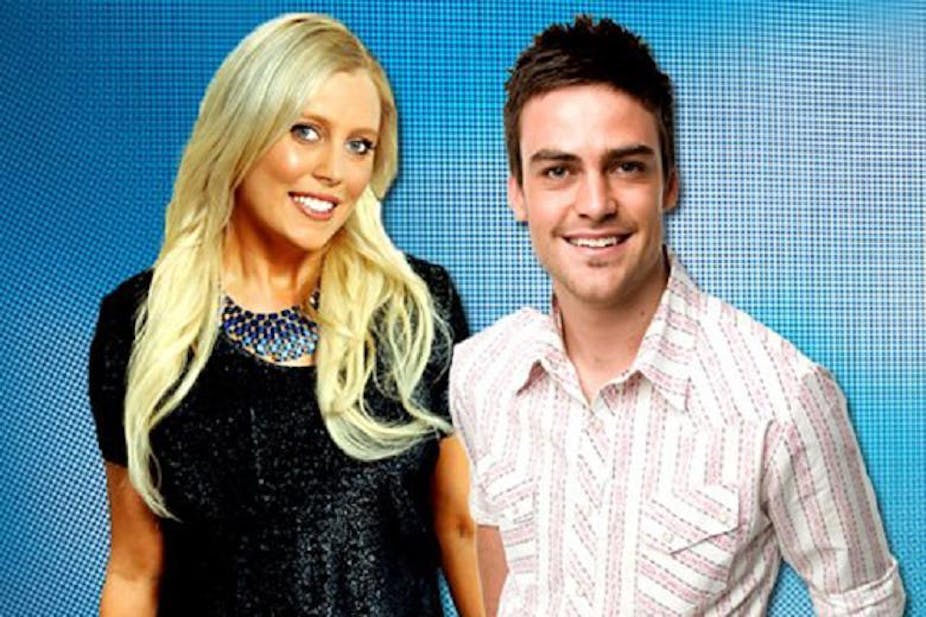

Sadly, few of those outraged over the Kate Middleton hospital prank will understand that the presenters responsible are not journalists but entertainers. For that role they are covered by the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) and not the ethics of Media and Entertainment and Arts Alliance (MEAA).

If they were covered by the MEAA, warning bells would have rung well before the piece was put to air. Such a prank does not fit with the journalistic rules of honesty, fairness, independence and the rights of others.

Kate’s health might have great public interest, but any woman in the early stages of pregnancy deserves privacy and to be kept safe from the stress of the public gaze. If the presenters were journalists, they would have had to pay attention to an ethics clause that says, “Do not allow advertising or other commercial considerations to undermine accuracy, fairness or independence”.

And that’s the main point of this. The decision to put that prank to air was commercial. The presenters at the centre of the hospital prank were out to win in a cut-throat ratings city.

But just like the contestants in The Hunger Games, the ones who are really to blame are those behind the antics: the audience members who voted overwhelmingly that it was a good gag, and the program directors, company directors, and lawyer who approved it going to air. The lawyer decided there was nothing illegal in the actions, but did anyone in the room reviewing the pre-recorded program piece have a moral compass?

Sadly, the only way to get a moral compass for some, it appears, is to be threatened with big stick. So here is another potential villain in this saga: ACMA. If the Australian Communications and Media Authority had had a track record of being stronger, then perhaps someone would have stopped that piece going to air.

ACMA is the same body that sent Alan Jones for “fact” training, and gave John Laws a mere reprimand for the cash for comment scandal. If ACMA had taken a harder line with these matters and with Kyle Sandilands for his foul comments to a rape victim and subsequently a female journalist, would someone at Austereo have stopped to think harder and longer about putting this piece to air?

It’s not as though episodes like this were not already on the radar for Australian media as being a potential ethics and legal storm. Remember when Channel Seven got in trouble for its hospital invasion in the wake of the Christchurch earthquake?

Will ACMA now consider revoking the station’s broadcasting licence? It’s unlikely.

Prank calls are for teenagers. It’s time commercial radio contributed to lifting the public discourse in this country and stopped pandering to the lowest common denominator. Maybe it’s time for breakfast radio to ditch its infantile persona and aspire to something better.

They need to do so for all of us who have had a loved one in hospital and have relied on nursing staff to tell us, “Get on a plane now” or, “It’s okay, you don’t need to worry”. I wonder how many nurses will now tell us nothing by phone until we disclose our mother’s maiden name.

I spend a lot of time in my classes talking about the need to treat people (such as nurses) with respect. I try to ensure they are fully aware of the impact of media glare on the general public, particularly those under stress.

Sadly, there will always be a percentage of media workers out there who will push the boundaries in a misguided attempt to get a scoop. Big companies including hospitals should be prepared to manage that. A couple of night duty nurses shouldn’t have been left exposed to cop the flack. This is one of the few good reasons we have public relations specialists.

But in the end, it’s media companies who must be held accountable for this kind of stunt. It’s time for ACMA to step up.