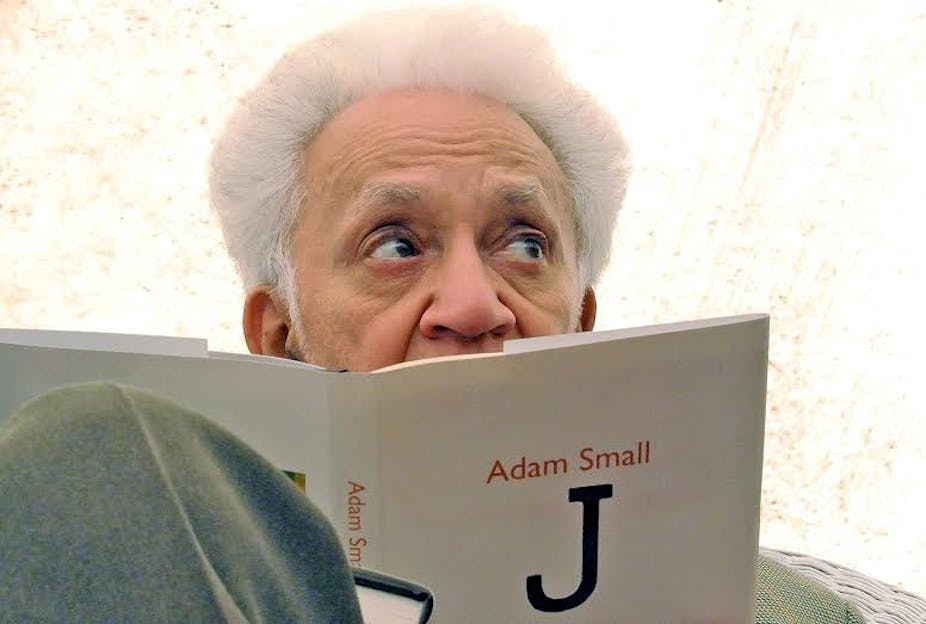

The death on June 25 2016 of Adam Small, the South African Black Consciousness activist, Afrikaans poet and revered academic, was not unexpected. In the twilight of his years, in his public interactions, he came across as alert but increasingly frail, often teary-eyed. In his last creative writings such as “Klawerjas” (2013) and “Maria, Moeder van God” (Mary, Mother of God, 2015) he often referenced impending death or retraced the vagaries of a life lived.

Small always had an air of compassionate consideration, of thoughtfulness, of critical engagement. He treated ideas seriously and death, like life, was something to be explored. At the death of his mother, of Muslim Indian heritage, he thanked her “for everything and thinking of Goree / for reading and writing … / /… your sense of humour…”

He was born on December 21 1936 in the small town of Wellington, about 70km northeast of Cape Town. He grew up in a village called Goree where his father, a slave descendant and a Dutch Reformed Protestant, was a primary school teacher.

The family later moved to Cape Town where Small completed his secondary schooling and later an MA thesis at the University of Cape Town on “Nicolai Hartmann’s appreciation of Nietzsche’s axiology”. He completed most of his schooling through the medium of English. Small however found his artistic niche in liberal intellectual thought, and Afrikaans literary, cultural and linguistic association.

Afrikaners aren’t only white

From early on he confessed a close kinship with Afrikaans. He even identified himself as an Afrikaner. It was a very controversial statement at a time when the appellation “Afrikaner” was reserved for Afrikaans-speaking white people. Small’s association was cultural and linguistic.

Throughout his life, from his long essay “Die Eerste Steen” (The First Stone, 1961) to his play “The Orange Earth” (or “Goree”, 1978; 2013), he maintained that one of the greatest injustices that apartheid brought about was that people who spoke the same language and shared the same cultural heritage were arbitrarily divided on the basis of skin colour.

For him apartheid was an abomination that denied people the experience of their most basic humaneness and humanity. The very basis of monochromic apartheid was anathema to him: he grew up in a house that was defined by its syncretism, its multiculturalism and its multilingualism.

As a young writer and a keen polemicist he became a controversial figure, often taking positions that people on the right and the left, or the side of the apartheid regime and their opposition found unpalatable. For Small was his own man, not given to groupthink or the unearned graces of political masters.

His first collections of poetry “Verse van die Liefde” (Love Poems, 1957) and “Klein Simbool: Prosaverse” (Little Symbol: Poetry in Prose Form, 1958) were acknowledged as the beginnings of a budding poet.

Small finds his voice

He found his voice in “Kitaar my Kruis” (Guitar my Cross, 1961). Here, he writes with sure-footedness. Small expressed himself in an idiom of which few of his fellow Afrikaans writers had intimate knowledge or had regular access to.

In a foreword to a reprint of “Kitaar” he defended his use of the vernacular at a time when (white) Afrikaner nationalists promoted “pure Afrikaans” as “civilised or standard Afrikaans”. The argot of the Cape Peninsula’s coloured working class, often ridiculed as “Gamattaal” or “Capey”, was regarded as the abject speech of deficient beings who could barely aspire to the lofty speech of “civilised Afrikaans”.

Small named this vernacular, creolised urban Afrikaans, Kaaps. He became its most persistent defender and promotor: “Kaaps is a language … people live their whole lives ‘with everything in it’ … Kaaps is not a joke or funny … it is a language.”

Thereafter, most of his better known works such as the poetry collections, “Sê Sjibbolet” (Say Shibboleth, 1963) and “Oos Wes Tuis Bes Distrik Ses” (East West Home Best, 1973, with Chris Jansen) were written in Kaaps.

He also valorised this language variety in his plays “Kanna Hy Kô Hystoe (Kanna, He Comes Home, 1965)”, “Joanie Galant-hulle” (Joanie Galant-them, 1978) and “Krismis van Map Jacobs” (Christmas of Map Jacobs, 1983) or the novella, “Heidesee” (1979). In those works he gave voice to the downtrodden, those marginalised by the imposition of the apartheid policies of spatial and social separation, and political repression.

The introduction of formalised apartheid in 1948 caused a generation of black professionals, particularly those classified as coloured or mixed race, to emigrate to Britain, North America and Europe. The absent character in Small’s best-known play, “Kanna Hy Kô Hystoe” is Kanna.

Foremost literary work

Kanna is one of those emigrants who found a new, welcoming world elsewhere and left a struggling family behind. The play is universally considered one of the foremost Afrikaans literary works. It’s not only for its profound social message, and its linguistic and textual plurality, but also for its theatrical experimentation.

One of the pernicious, enduring consequences of the apartheid policy is its destruction of social life. The demolition of the old inner city area of Cape Town, District Six, was emblematic of this legacy. Increasingly during the 1960s and 1970s Small wrote in his newspaper columns and open letters against apartheid broadly, especially against the Group Areas and Population Registration Acts.

His voice was most strident in the Afrikaans newspapers, and he was often described as “embittered”. To the apartheid authorities Small was an irritant. The security police at times made his life miserable. Perhaps his fame as an Afrikaans writer insulated him from possible terrible outcomes such as unlawful incarceration or preventive detention.

During the 1970s he found himself at odds with his place of work, the University of the Western Cape, where he in solidarity with protesting anti-apartheid students, resigned as a senior lecturer in philosophy. He later returned, under vastly different circumstances, and became professor of social work until his retirement in 1997.

Black Consciousness

From a writer who closely associated with Afrikaans literature, and even the luminaries of its tradition, Small’s thinking and writing had evolved and took a different turn in the 1970s.

Small became an important campaigner for the Black Consciousness movement. He even testified as an expert witness in the famous South African Student Organisation trial where he said that “the coloureds were part of the greater black community”. He added that “a violent war between black and white was a distinct possibility”. During this period he wrote the first of a number of English medium works, but most of his English plays and poetry remain unpublished.

Although Small is acknowledged as one of the foremost Afrikaans writers, literary award committees often found ways of not awarding his outstanding works. Recognition mostly came belatedly. In 1993 Small accepted the South African Order for Meritorious Service (Gold) from the last National Party administration under FW de Klerk.

He was awarded four honorary degrees – from the universities of Natal (1981), Port Elizabeth (1996), the Western Cape (2001) and Stellenbosch (2015) – and a number of cultural and literary awards in later life.