To our horror, another mass coral bleaching event may be striking the Great Barrier Reef, with water temperatures reaching up to 3°C higher than average in some places. This would be the sixth such event since the late 1990s, and the fourth since 2016.

It comes as a monitoring mission from the United Nations arrives in Queensland today to inspect the reef and consider listing the World Heritage site as “in danger”.

As coral reef scientists, we’ve seen firsthand how the Great Barrier Reef is nearing its tipping point, beyond which the reef will lose its function as a viable ecosystem. This is not only due to climate change exacerbating marine heatwaves, but also higher ocean acidity, loss of oxygen, pollution, and more.

Scientists are at our own tipping points, too. The reef is suffering environmental conditions so extreme, we’re struggling to simulate these scenarios in our laboratories. Even though Australia has world-class facilities, we are proverbially beating our heads against the wall each year as conditions worsen.

It’s getting harder for scientists to predict how these conditions will affect individual species, let alone the health and biodiversity of reef ecosystems. But let’s explore what we do know.

What is coral bleaching and why does it happen?

Corals are animals that live in a mutually beneficial partnership with tiny single-celled algae called “zooxanthellae” (but scientists call them zooks).

Zooks benefit corals by giving them energy and colour, and in return the coral gives them a home in the coral tissue. Under stress, such as in too-hot water, the algae produce toxins instead of nutrition, and the coral ejects them.

Read more: 5 major heatwaves in 30 years have turned the Great Barrier Reef into a bleached checkerboard

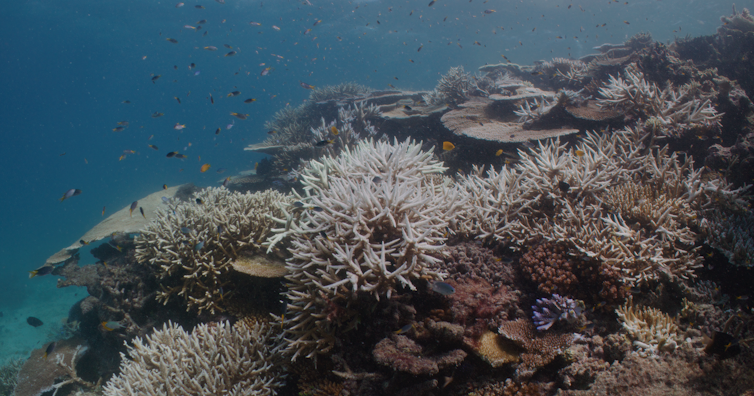

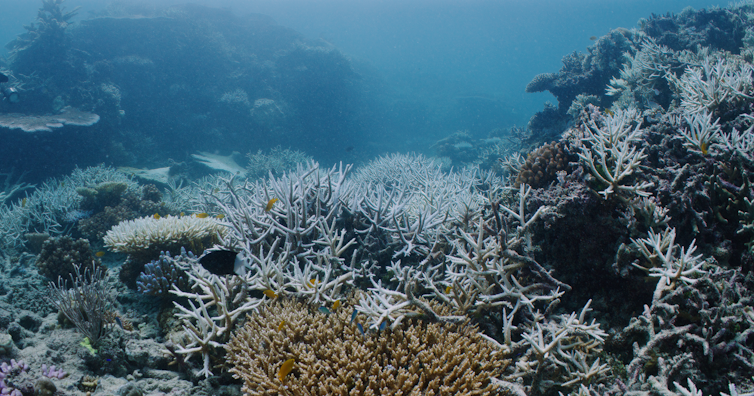

Without the algae, the corals begin to starve. They lose their vibrant colours, revealing the bright white limestone skeleton through the coral tissue.

If stress conditions abate, the algae can return and coral can recover over months. But if stress persists, the corals can die – the skeletons begin to crumble, removing vital habitat for other species.

We had hoped for a reprieve

Scientists and managers had hoped for a reprieve this year. Much of the Great Barrier Reef was in the early stages of recovery following the 2016, 2017, and 2020 bleaching events.

In the tropical paradise of northern Queensland, we’ve been wishing for cloudy days and cooler temperatures, hoping for rain and even storms (but not big ones). These conditions typically come with La Niña – a natural climate phenomenon associated with cooler, wetter weather, which has now happened two years in a row.

But despite these effects of La Niña, climate change meant 2021 was one of the hottest years on record. Now, at the tail end of Australia’s summer, the reef is experiencing another marine heatwave and is tipping over the bleaching threshold.

There’s not enough time for coral to recover between events. Even the most robust corals require nearly a decade to recover. There is also no clear evidence corals are adapting to the new conditions.

To make matters worse, climate change is supercharging the atmosphere and making even the natural variations of La Niña and its counterpart El Niño more variable and less predictable. This means Australia will not only endure more intense heatwaves, but also flooding, droughts and storms.

How will this hurt marine life?

A healthy Great Barrier Reef is home to at least 1,625 species of fishes, 3,000 species of molluscs, 630 species of echinoderms (such as sea stars and urchins), and the list goes on.

Marine life in coral reefs have three options in warming waters: adapt, move, or die.

1. Can they adapt?

Over generations, species can make changes at the molecular level – their DNA – so they’re more suited to or can adapt to new environmental conditions. This evolution may be possible for species with fast generation times, such as damselfishes.

But reef species with slower generation times can’t keep pace with the rate we’re changing their habitat conditions. This includes the iconic potato cod and most sharks, which take a around a decade or longer to reach sexual maturity.

2. Can they move?

Some species of reef fishes may start moving to cooler waters before the harmful effects of warming take hold.

But this option isn’t available to all species, such as those that depend on a particular habitat, certain resources, or protection. This includes coral, as well as coral-dwelling gobies and several damselfishes.

A citizen science project called Project RedMap, has been documenting the poleward migration of reef fish species due to climate change. Studies have found that larger, tropical fishes with a high swimming ability are more likely to survive in temperate waters, such as some butterflyfishes.

3. They can die

The third option is one we don’t like to talk about, but is becoming more of a threat.

If marine life can’t adapt or move , we’ll see extinctions at a local scale, total extinction of some species, and dramatic declines in fish populations.

Listing the reef as ‘in danger’

While the reef is bleaching, UNESCO delegates have arrived in Queensland to monitor its health, as the World Heritage site is once again being considered for an “in danger” listing.

The visit will likely include seeing the bleaching currently occurring, the damage to the reef still apparent from past events, and they’ll hear firsthand from scientists and managers who’ve witnessed these impacts.

Listing the Great Barrier Reef as “in danger” would raise the alert level for the international community and hopefully inspire climate action.

Reducing the major source of stress the reef faces – climate change – will require ongoing collaborations between Australian and international governments, with work on local management issues also involving business owners, reef managers, Traditional Owners, scientists, civil society groups, and other stakeholders.

We’ve known for a long time the most important step to save the reef: cutting emissions to stop global warming. Indeed, future projections of coral bleaching from the 1990s suggested that frequent and severe events would begin from the late-2010s – and they’ve been alarmingly prescient.

The Great Barrier Reef’s continuing demise is one of the most visible examples of how our inaction as humans has profound and perhaps irreversible consequences. We are rapidly accelerating toward the tipping point.