Australians have just celebrated Mabo Day – this year marking the 20th anniversary of the landmark High Court decision that changed the course of land rights in Australia

The case has special resonance for us here at James Cook University.

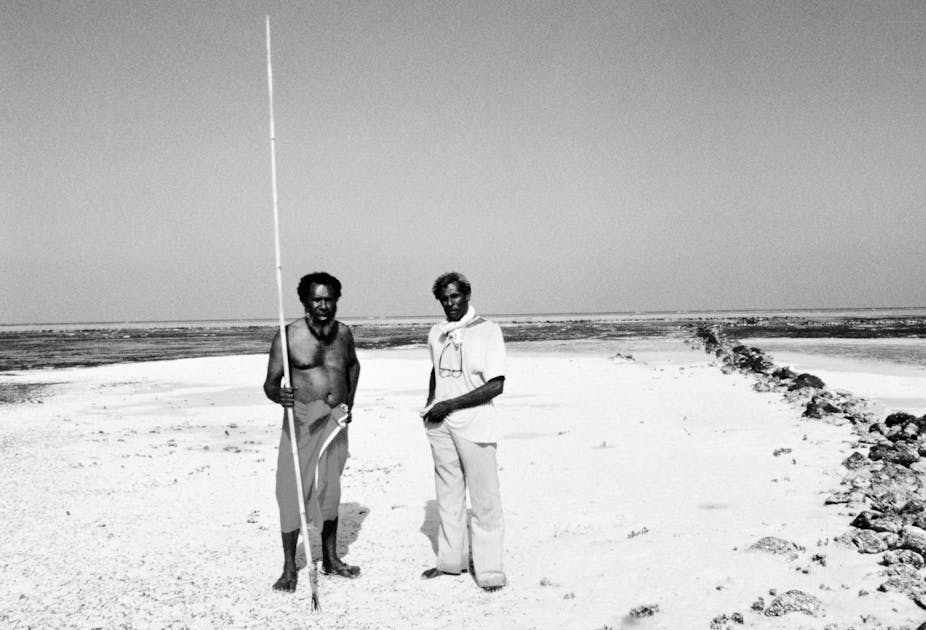

It is here, on our Townsville campus that Eddie Koiki Mabo worked and shared the story of his people and his land with historians Henry Reynolds and Noel Loos. At a conference at James Cook in 1981 the seeds were planted to challenge the dispossession of the Meriam people.

Against this backdrop, I have been reflecting on the Mabo decision and what it represents for me: a non-Indigenous Australian lawyer. To me, this story is about the possibilities of the law as a means of progressive change and importantly, about reconciliation itself.

The possibilities of common law

One of the things I love about the Mabo decision is that it shows how the existing legal system can be used constructively against itself.

The Meriam people in Mabo used the common law to reinvent the law’s own (English) conceptual framework of land ownership that had previously applied in Australia. There was no suggestion that in using the common law the applicants had accepted or internalised these (English) values and culture. In legal argument, the applicants did not seek to challenge the sovereignty of the dominant group, but sought to stand alongside this introduced culture within its own broad framework.

Importantly also, the court did not seek to absorb the traditional law and custom of the Meriam people: it did not usurp their “native title” but recognised it as a separate system. As a result of their action, the Meriam people became a group whose own laws were recognised by the common law.

This is the possibility implicit in the common law: the possibility to accept people and culture on their own terms.

Identity and the law

The Mabo decision highlights the law’s capacity to create cultural identity. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, the law has embodied a fiction that literally renders them invisible, as a means of justifying sovereignty. This translates to a domestic law principle that pre-Mabo justified Crown ownership of land to the exclusion of traditional owners.

These doctrines and principles embody a European view of culture that negates the capacity of traditional cultures to support connection to land. The power of the Mabo decision lies partly in its recognition that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures do have capacity to support connection to land in a way that is recognisable at (Anglo-Australian) law.

The power we invest in the law to validate cultural expression of land connection is a double-edged sword however, and we celebrate Mabo as the positive side of this. But the law continues to tell Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians that it will not recognise their connection to land, impliedly thus rejecting their culture.

The Yorta Yorta decision is an example of this in which the Court found that “the tide of history has indeed washed away any real acknowledgement of their traditional laws and any real observance of their traditional customs.” The law thereby purported to construct the culture of the Yorta Yorta people.

It is important to celebrate the victory of Mabo, but also to be wary of leaving ourselves vulnerable to the power of the law to render us invisible.

Creative legal thinking

Finally, for lawyers, the Mabo decision represents a high water mark in legal thinking: thinking outside what might seem possible. The elegance of the argument in Mabo cannot be disputed.

As Michael Kirby said of Ron Castan QC, one of the counsels in Mabo:

“It is advocates, as much as judges, who shape the destiny of the common law. By their imagination, learning, courage and forensic skills, advocates create the agenda and map the course of the greatest legal developments.”

Ron Castan was “widely credited with shaping the High Court’s decision in that case.” “Without [his] vital contribution [along with Eddie Mabo] … the Mabo cases would never have survived their ten-year torturous course - let alone succeeded.”

This capacity for creative thinking, however, was inspired by something more. For lawyers, it is necessary to be intelligent and skilled - but it is not sufficient. Kirby points out that for Ron Castan QC, “his was a spiritual journey of love unbounded.” It is this quality that will enhance the capacity for lawyers’ creative engagement in the law, and their capacity for embodying justice - and in the Mabo case, of living reconciliation.

The Mabo decision represents a powerful dignity. Dignity of those who persisted to bring this case, as well as dignity in the common law - a system with the capacity for imagination and flexibility and justice.