When the ancient Egyptian priest and landowner Heqanakhte wrote a series of rather acerbic letters to his extended family sometime during the 12th Dynasty (1991-1802BC), he could not have known that he was creating the framework around which the British crime writer Agatha Christie (1890-1976) would, some 4,000 years later, weave one of the world’s first historical crime novels.

Death Comes as the End (1944) is the only one of Christie’s novels not to be set in the 20th century and not to feature any European characters. The death of a priest’s concubine sets off a series of murders within the family and, as in Christie’s more familiar 20th-century whodunnits, the scene is soon littered with bodies. The book is due to be adapted for the screen by the BBC in 2019.

While there are numerous plot parallels in the Heqanakhte Letters (as these papyri would come to be known), the letters themselves provide an unparalleled glimpse into land management and everyday family life in ancient Egypt. In the letters, Heqanakhte provides his children with meticulous calculations of crop yields and instructions for land investments followed by the stern injunction that he would consider any deviation from his instructions akin to theft.

The letters also contain allusions to some disharmony within the family caused by the recent addition of Heqanakhte’s second wife to the household, much like in the novel where the arrival of Imhotep’s concubine, Nofret provokes murderous hatred.

The Heqanakhte Letters are trivial in their content but unique in their form: It is very rare for this level of detail concerning the family dynamics to survive the thousands of years which separate us from Middle Kingdom Egyptians. The letters were found in the 1920s by American archaeologists from the Metropolitan Museum of Art while excavating the tomb of the Middle Kingdom vizier Ipi near modern-day Luxor. Translations of the papyri and scholarly investigations followed shortly afterwards, a study which continues to this day.

Christie in Egypt

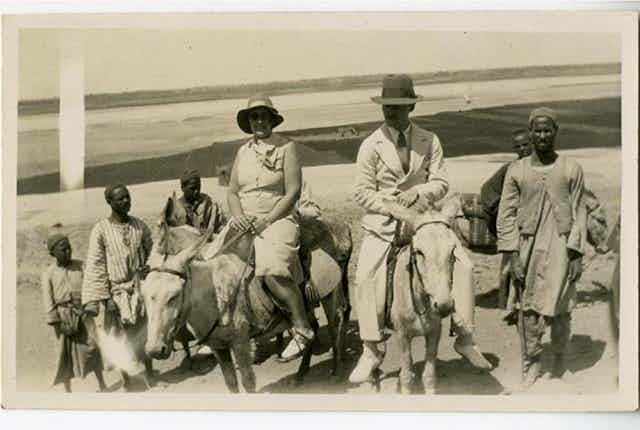

Christie certainly knew a thing or two about both ancient and modern Egypt. She first visited the country as a young woman in the winter of 1910, staying with her mother Clara for three months at Cairo’s glitzy Gezirah Palace Hotel. The experience had a clear impact on her – her first (unpublished) novel Snow Upon the Desert (1910) was set in Cairo.

Later, she drew further on her experience of life in Egypt and the experience of tourists visiting the country during the first half of the 20th century when writing the short story, The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb (1923) and, 14 years later, Death on the Nile, which follows the orotund Belgian detective Hercule Poirot as he attempts to solve the (some might argue needlessly complicated) murder of a wealthy heiress honeymooning in the Land of Pharaohs. In other words, peak Christie.

Christie’s marriage to British archaeologist Max Mallowan in 1930 reinforced her fascination with the ancient Near East and ancient Egypt. The marriage – and the financial success of her novels – provided her with ample opportunity to travel both as a tourist and an archaeologist in the region, experiences which in turn resulted in the autobiographical Come Tell Me How You Live (1946) and inspired further travels for her fictional Belgian detective in Murder in Mesopotamia (1936) and Appointment with Death (1938).

Bringing Egypt to life

However, it was her friendship with the Egyptologist Stephen Glanville, a professor at University College London who served with Mallowan during World War II, which prompted her to explore the possibility of writing a historical whodunnit moving her narrative from Art Deco drawing rooms to the dusty desert on the Theban West bank. Death Comes as the End was written by Christie during the height of war and, as Christie herself states in the author’s note, “the inspiration of both characters and plot was derived” from the Heqanakhte letters. Glanville served as a historical sounding board and consultant, a role for which he was eminently suited, having written the seminal book Daily Life in Ancient Egypt in 1930.

While the book received praise from critics upon its publication in 1944, it did cause some ructions in Christie’s own family life. Mallowan was not altogether happy that she had collaborated with Glanville. He wrote to Glanville expressing concern about the work to which Glanville rather pointedly replied: “I am not clear whether you are afraid that the book will damage her reputation as a detective story writer, or whether you think that archaeology should not demean itself by masquerading in a novel.”

Death Comes as the End is not among Christie’s most famous works, but it remains a fascinating experiment: a marriage between archaeology, Egyptology and fiction writing, a formula many later authors have dutifully followed. Along with Christie’s other works set in Egypt and the Near East it is also a tangible testament to the enduring fascination Western societies have for these ancient cultures.