The first Iraqis to appear in Clint Eastwood’s Iraq War drama, American Sniper, are a young mother and boy of maybe 12. They are seen from the point of view of the man who will kill them: Chris Kyle, the real-life Navy Seal whose tours in Iraq provide the narrative for this controversial movie.

Through his high-powered scope on a nearby rooftop, Kyle watches the mother, shrouded in her burqa and ḥijāb, hand a grenade to the boy and send him through the rubble towards a squad of American troops.

Kyle, though tortured by having to do it, executes them both.

But the movie does not pause to register the tragedy of their deaths. The drama in the scene – and throughout the movie –- turns on the crisis for Kyle, of the moral and emotional consequences of the war for him.

The woman and child, like all Iraqis in the film, are rendered as conspicuously “other”: distant, dangerous, unknowable and malevolent. In this scene, for example, Eastwood does not show us their fear or anguish. Filming the action from Kyle’s point of view keeps them at a remove from the viewers’ sympathies.

What’s more, the movie fails to provide any kind of larger context that might explain their actions. Except for a few throwaway lines, American Sniper does not delve into the circumstances surrounding the Iraq War and what many consider the US crimes and fabrications that led to it.

It certainly doesn’t present a point of view in which Iraqis, still reeling from the trauma of decades of totalitarian oppression, are seen as protecting their homeland from brutal foreign occupiers.

Instead, the Iraqis are derided as “savages” in the film by Kyle and others. And though that may represent attitudes held by the characters, Eastwood does not make it clear enough that the filmmakers don’t share their views, one of the reasons why the liberal U.S. media has criticized the film.

These critics are correct when they say that American Sniper is consistent with historical representations of Arabs in Hollywood movies. As Jack Shaheen, who has done pioneering work on the subject, writes

Seen through Hollywood’s distorted lenses, Arabs look different and threatening. Projected along racial and religious lines, the stereotypes are deeply ingrained in American cinema. From 1896 until today, filmmakers have collectively indicted all Arabs as Public Enemy #1 – brutal, heartless, uncivilized religious fanatics and money-mad cultural “others” bent on terrorizing civilized Westerners.

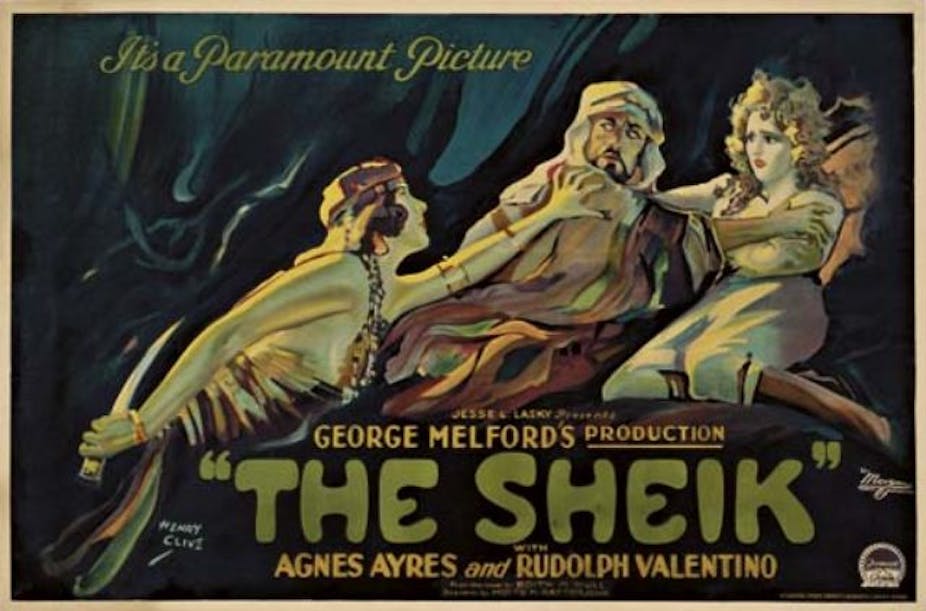

In his work, Shaheen has analyzed virtually every Hollywood feature ever made that depicts Arabs, ranging from The Sheik (1921), to Disney’s Aladdin (1992), to Rules of Engagement (2000). He found that they are almost invariably depicted as “brute murderers, sleazy rapists, religious fanatics, oil-rich dimwits and abusers of women.”

Of course, these characters certainly don’t reflect the diversity and multiplicity of real Arabs who number in the hundreds of millions and contribute to a mosaic of cultures, languages and religions throughout the Middle East.

While other non-white groups, such as African Americans and Latinos, have arguably seen their representation in Hollywood films improve and diversify over time (at least marginally), Arabs and others of Middle Eastern descent continue to be maligned and silenced, still used as easy villains in recent movies such as Iron Man (2008) and Lone Survivor (2013). Even films that humanize them, such as Three Kings (1999), Syriana (2005), and The Hurt Locker (2008), still operate from white, American points of view and often feature Arabs as weak and backward.

Despite what could be described as more racially progressive work in earlier films – Flags of Our Fathers (2006), Letters From Iwo Jima (2006), Gran Torino (2008) – Eastwood engages in these traditional patterns of representation in American Sniper.

In one scene, Kyle and his men kick in the door of a family to use their house as a staging area. After a time, the family invites Kyle and his men to dinner. During the meal, Kyle suspects that the man is an insurgent. He leaves the table and searches the house, finding a cache of weapons: the man is the enemy he is suspected of being, and Kyle brutalizes him. Later, like so many of the Iraqis in this film, the man is mowed down by a US machine gun.

Compare this to a scene in Gran Torino, in which Eastwood’s character, a curmudgeonly old Korean War vet living in Detroit, is invited to dinner at the house of his next-door neighbors, who are Hmong people from Laos. The scene runs for almost ten minutes, as Eastwood lingers on three generations of immigrants – their customs, hardships and relationships to one another. Eastwood does more then humanize the Hmong in Gran Torino; he attempts to normalize them as people no different from their white neighbors, and portrays them with great deal of empathy.

Empathy is what’s missing in American Sniper – at least towards the Iraqis. And it’s Eastwood’s more progressive work that especially renders American Sniper such a disappointment. Given the opportunity to represent Iraqis with the depth and humanity he’s shown to non-whites and non-Americans in previous films, he instead succumbs to the same patterns of representation that have demonized Arabs in American film for a century.