The global economy was flashing danger signs long before the pandemic. For one thing, many countries were clamouring to get hold of as much gold as possible. For the past decade, they have been buying new reserves and bringing it home from overseas storage to an extent never seen in modern times. Then just before the pandemic, there was a pause. What does all this mean?

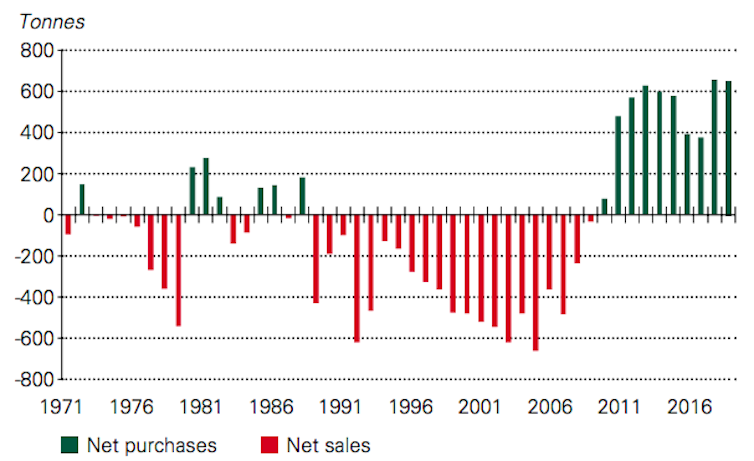

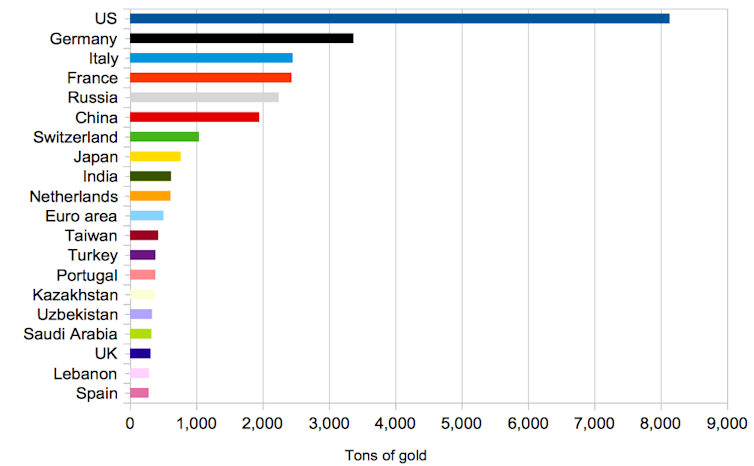

Central banks added 650 tons to their reserves in 2019, the second highest shift in 50 years, after the 656 tons added in 2018. Before the 2007-09 financial crisis, central banks were net sellers of gold worldwide for decades. Leading the recent spree has been China, Russia, Turkey, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Central bank gold buying 1971-2019

We have also seen a large effort by central banks to repatriate their gold from other countries, mostly from storage in New York and London.

Gold has enthralled humanity since ancient times. Still it glitters from central bank vaults to jewellery bazaars the world over. The Conversation brings you five essential briefings by academic experts on the world’s favourite precious metal. For more articles written by experts, join the hundreds of thousands who subscribe to our newsletter

Venezuela started repatriating its gold in 2011, shipping 160 tonnes from New York. A third of its holdings remain in London, but only because the Bank of England won’t repatriate them – declaring it doesn’t recognise the government in Caracas. Venezuela has now made this the subject of a legal claim.

Between 2012 and 2017, Germany repatriated most of its massive reserve from Paris and New York to Frankfurt. The Netherlands did likewise in 2014, followed by Austria.

Top 20 national gold reserves

Then came Eastern Europe. In 2018, Hungary announced it would repatriate nearly 3 tons of gold from London, while greatly boosting its reserves. Poland repatriated 100 tons from London a year later, about half of its national reserve. Next was Romania, while Slovakia and Serbia have been considering moving gold home from England too.

Why it is happening?

This dash to gold is about geopolitics and economics. Gold serves as a patch mark of nationalist identity. To quote Adam Glapinski, governor of the National Bank of Poland, “gold symbolises the strength of [a] country”.

Stocking up has made sense to many countries in the populist climate. It is also a sign of countries diversifying from dollars. The likes of Russia, China and even countries in Western Europe want to break the US dominance of the financial system, having seen it used as leverage in everything from economic sanctions to trade threats.

Following the last financial crisis, many also feared there was more to come. When former Slovak prime minister Robert Fico last year urged his parliament to compel the central bank to repatriate gold from London, he argued that overseas reserves could be at risk in a new global economic crisis.

Citing the 1938 Munich pact between France, Britain, Italy and Germany that allowed the German invasion of Czechoslovakia, he said that “sometimes your international partners can betray you”.

Countries also seem unnerved by the row over Venezuela’s gold, plus the fact that Germany’s repatriated bars from the US appeared different to what it thought was in store. This suggested the Federal Reserve was trading them.

Fiat vs gold

In an era where everything is digital, fast and smart, it might sound strange that a static piece of metal could still have a major monetary role. Central banks abandoned the gold standard in the 1970s, led by US President Richard Nixon, which meant that paper currencies were no longer exchangeable for gold. This was necessary because there were too many dollars in the international system and too many countries exercising their right to exchange them for US gold reserves.

After Nixon’s decision, currencies became fiat, meaning that countries could freely decide how much to have in circulation. Currencies now had value not because they were backed by gold, but because the state standing behind them said they had value. Central banks effectively declared gold to be a relic. Fiat money was seen as superior, thanks to central bankers’ supposedly scientific oversight of monetary policy.

The new dash for gold makes economists pause and wonder what is happening. It seems to show many countries looking for a safe haven in these years in which interest rates have been very low and central banks have been printing large amounts of money to stimulate the global economy. Gold continues to have intrinsic value, so it reassures countries – especially if they fear inflation and downturns.

And yet, just as economic uncertainty was about to move to a whole new level with the pandemic, this trend lost momentum. Additions to the gold holdings of central banks and other international institutions in the three months to January 2020 – the most recent figure available – were just 67 metric tons, the least since August 2018.

In truth, this was not entirely surprising. Purchasing bullion at close to a seven-year high, and after a month of prices fluctuating plus or minus about 13%, is no particularly prudent way to consolidate economic and geopolitical power.

It will be a few months before we see how the pandemic has affected central banks’ attitude to gold. It could yet convince them that gold will still move higher. So don’t be surprised if this dash to gold has resumed in recent weeks – in a leading indicator of troubling times ahead.

If you liked this article, find more expertise in our gold series:

Why gold prices go up and down – five charts

Since the demise of the gold standard in the early 1970s, the precious metal has gone through four distinct phases.I’m a bit of a modern-day alchemist, recovering gold from old mobile phones

There’s 33 times more gold in the average handset than in the equivalent amount of ore. Yet the vast majority is never recovered.Meet the struggling gold miners who are missing out on the boom in precious metals

You would think that anyone in the gold industry would be getting rich right now, but informal miners in many countries are missing out.How the US government seized all citizens’ gold in 1930s

It seized all gold bullion and coins, forcing citizens to sell at well below market rates. Then, immediately after the “confiscation”, it set a new official rate for gold that was much higher.Subscribe to our newsletter

Get more news and information you can trust, direct from the experts.