I looked around the lecture theatre and scribbled down what the lecturer had said: ABCD. ACE inhibitors (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors), Beta blockers, Calcium channel blockers and (thiazide) Diuretics. These were the four groups of drugs used to treat high blood pressure (hypertension) – except there were exceptions.

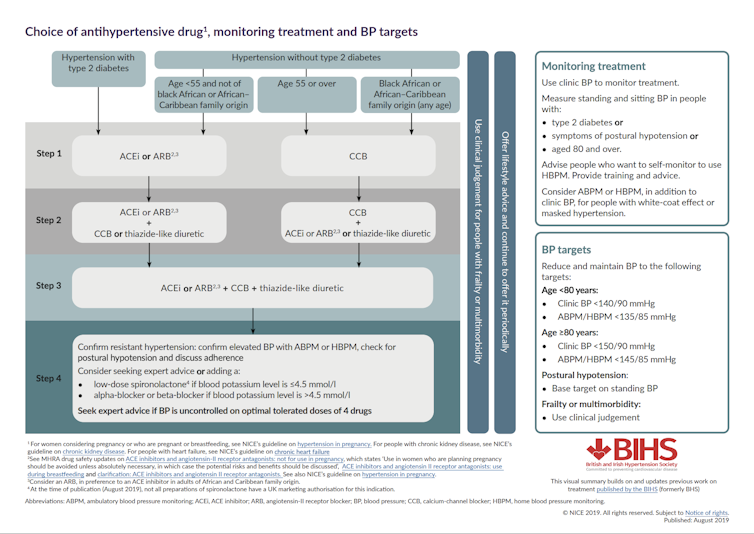

We didn’t use beta blockers anymore and ACE inhibitors don’t work for black people, specifically black African or Afro-Caribbean people. The lecturer explained to us that all black people were inherently less likely to respond to ACE inhibitors. This is what I learned at medical school, and this is what medical students still learn today. Now, as a practising GP, this is the guidance we use every day (click to make them bigger).

On the other hand, in the US blood pressure guidance, there is no mention of race. Why the disparity? Do black people really react to blood pressure drugs differently from white people? Are black bodies different from white bodies?

Speculation on why black people have higher blood pressure than white people is often attributed to a genetic adaptation to slavery: specifically, salt retention allowed black people to survive long trips on slave transportation ships across the Atlantic Ocean. The implication that there are inherent biological differences between black people and members of other races has entered blood pressure medication guidance. Black people are labelled “low-renin responders” so are less likely to respond to ACE inhibitors. But there are several things wrong with this idea:

The highest quality evidence (a meta-analysis) found a small but statistically significant 4mmHg (millimetres of mercury) difference between the response to ACE inhibitors between black people and white people. If black people were all poor responders to this drug, you would expect the difference to be far bigger.

There is conflicting evidence on whether ACE inhibitors are beneficial or detrimental in terms of heart disease outcomes for black people. If they didn’t work that well, surely there would be no change or a clear detriment.

Even if black people are inherently different from white people, what medication should a person receive if they have a black parent and a white parent? What if they have a grandparent of African heritage? Using the “one-drop rule” – where any person with even one ancestor of black ancestry is considered black – could be problematic as very few people can trace their ancestry back a few generations. This means it is difficult to rule out any African or Caribbean heritage in anyone’s lineage. A commercial genetics test probably won’t help you.

Recent genetic research consistently shows that there are greater genetic differences between members of the same race compared with members of different races, looking generally and specifically at African-Americans.

The social and economic circumstances and the environment in which a person lives has a greater effect on health than biological or genetic factors. So could there be an alternative explanation for why black people have higher blood pressure compared with white people? Could poverty, stress or perceived racism be reasonable explanations?

Decolonising medicine

Medicine is not objective; scientific research is conducted by people who bring their own perspectives. These biases colour the way research is conducted, the way data is analysed and the way conclusions are drawn. Perhaps it’s time for an overhaul.

The reform of medical curricula is called “decolonisation” where the impact of history and colonisation is examined so medicine can better meet the needs of people who come from ethnic minorities. In a recent example, medical student Malone Mukwende wrote a textbook to help doctors recognise skin conditions on black and brown skin. This is significant since skin conditions in medicine are almost exclusively taught on white skin.

Where it comes to blood pressure research, a more holistic approach is needed to involve other sectors, such as genetics and social sciences. The UK blood pressure guidelines need to be re-examined as does much of medicine. This re-examination will challenge assumptions and the objectivity of medical research. This may fill some members of the medical profession and the public with dread as this adds to further uncertainty during a global pandemic. Perhaps this is the beginning of a change that will lead to a fairer health system for all.