Since its first fossils were found more than 100 years ago, Hallucigenia has perplexed palaeontologists. Looking like a cross between a hockey stick and a pincushion, the 1cm to 5cm long creature was named to reflect its surreal and “dream-like” appearance. It was first described on its side, then upside down walking on its long spines, and finally inverted to walk on what we now believe were its legs. Even then, scientists have been unable to agree which end of the animal is the head and which is the tail.

My colleague Jean-Bernard Caron and I became interested in Hallucigenia when we found that electron microscopes could reveal new details of its fossilised spines and claws. This helped us establish the creature’s place in the tree of life by working out its evolutionary relatives. Given the dozens of specimens collected by Royal Ontario Museum teams from the Burgess Shale in Yoho National Park, Canada, we thought we might finally have a chance to understand this oddball animal.

Prior to our study, a large balloon-shaped orb at one end of the specimen had been interpreted as an amorphous head. We soon established that this wasn’t part of the body at all, but a dark stain representing decay fluids or gut contents that oozed out of the rear end of the animal as it was buried.

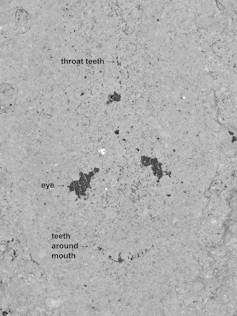

To find its head, we had to turn to the other end of the animal. Because the animals fossilised in the Burgess Shale died as they were trapped in a mudslide, their ends are often buried at a different angle to the rest of the body. Caron painstakingly chipped away at the rock to uncover the hair-wide head. Wondering whether the newly-exposed fossils might display eyes, I put them in the electron microscope. When I zoomed to what we hoped was the head, I was astonished to find not just a pair of eyes, but also a toothy grin smiling back at me.

This smile represented a ring of teeth in the mouth, which probably flexed in and out to suck in food. We also found another set of teeth lining Hallucigenia’s throat, which presumably stopped the food slipping back out of the mouth. This configuration of teeth reminded us of the arrangement in a group of moulting cuticular worms, the cycloneuralians, which include penis worms, roundworms, mud dragons and other bizarre microscopic creatures.

These animals have a ring of spines around their mouth and a tooth-lined gut that many can turn inside-out to ensnare prey. But Hallucigenia is not a cycloneuralian – it belongs to a group called the panarthropods, which includes the arthropods and the velvet worms. Based on a comprehensive analysis, we determined that arthropods and velvet worms once bore comparably complicated mouth parts, which were lost in the course of evolution.

This is exciting because it tells us something profound about the common ancestor of cycloneuralians and panarthropods – that is, all moulting animals. At first blush, the animals have almost nothing in common aside from the fact that they moult and some shared features in their DNA. If each group has independently evolved its own body plan, one might imagine that the common ancestor of the whole group was tremendously simple. Instead, we are now able to show that the common ancestor of moulting animals was a complex worm with teeth organised around its mouth and down its throat.

Hallucigenia’s unexpected mouth parts leave us wondering what more the animal might have up its sleeve. For example, our study revealed three pairs of tentacles emerging from Hallucigenia’s neck. What role did these impossibly narrow appendages serve?

The discovery of nerve tissue in other Burgess Shale animals is influencing our understanding of early animal evolution. Could new fossils reveal Hallucigenia’s brain? And Hallucigenia’s diet remains a matter of speculation – what food was the animal ingesting through its newly-discovered mouth?

I’ve always loved Hallucigenia for being such an unusual and surprising beast. Each time we uncover one of its secrets it seems to makes us think again about something we thought we knew. I only wonder what surprises Hallucigenia will reveal next.