I vividly recall my first encounter with Andrew Wyeth’s art when I was 14 years old, in the dingy galleries of Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum.

While giants like Picasso painted a world of artistic contrivance, Wyeth seemed to directly confront real life with an immediacy that I hadn’t encountered before. Yes, his drawings, watercolors and paintings seemed to capture the ramshackle character of New England with perfect accuracy. But they were also imbued with a powerful range of emotions: loneliness, the burdens of the past, the fragility of physical things, the struggle against a harsh climate and barren soil.

After this first encounter, I became a true believer in Wyeth’s work. It’s an opinion I still hold, though I’m aware that many others don’t share it.

On July 12, Wyeth would have turned 100. Over the course of his life and into his death, his reputation has weathered a whiplash of ups and downs and polarized opinion. In 1977, when the art historian Robert Rosenblum was asked to name the most overrated and underrated American artists, he nominated Andrew Wyeth for both categories.

How can we explain these dramatic shifts? And what do they say about how critics and artistic movements influence an artist’s legacy?

A star is born

From the 1940s to the 1960s, Andrew Wyeth achieved acclaim seldom, if ever, given to an American artist. On three occasions, major American museums acquired paintings he had made, with each purchase setting a new record for a living artist. In 1963, he appeared on the cover of Time magazine. Eight years later, Life magazine anointed him “America’s preeminent painter.”

The great connoisseur of Italian art, Bernard Berenson, wrote admirably about Wyeth’s work in his diary. The poet Robert Frost was an enthusiastic fan. The statesmen Winston Churchill, when he visited Boston, made arrangements to have Wyeth watercolors hang in his hotel room at the Ritz.

Some of his most passionate supporters were closely associated with the creation of the Museum of Modern Art: Lincoln Kirstein (the founder of the New York City Ballet), Elaine de Kooning (the art critic, painter and wife of the great abstract expressionist painter Willem de Kooning) and, most notably, Alfred Barr, the museum’s legendary founding director.

Barr, in fact, tracked Wyeth’s artistic progress with the obsessiveness of a stalker, just missing an opportunity to acquire a painting in 1941. He made up for his mistake in 1949, when he acquired Wyeth’s “Christina’s World.”

The painting quickly became one of the most popular works in the museum. Thomas Hoving, who later became director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, said he would sometimes visit the museum to study this one painting alone. “Christina’s World” was one of the first widely distributed color posters, and it became a popular addition to college dorm rooms.

Within a decade the museum had earned, from reproduction rights, over 100 times what it had paid for the painting. Wyeth had created an iconic image, a painting so unforgettable that it became implanted in the minds of millions of Americans.

From illustrator to artist

The achievement was particularly notable because Wyeth rose to prominence just when realistic painting was going out of fashion.

Abstract painting was elbowing everything else aside, and painters who had won national awards and acclaim in the 1930s were now finding that they needed to support themselves as illustrators, a profession that was increasingly derided as commercial.

In fact, Wyeth had close ties with the world of illustration: His father, N.C. Wyeth, had been one of America’s most successful illustrators, the source of action-packed imagery that stirred the imaginations of American boys in books such as “The Black Arrow” and “Treasure Island.” As a teenager, under his father’s auspices, Wyeth even illustrated a few boys’ books of his own.

But as Wyeth matured as an artist, he started making paintings in a style very much at odds with that of most commercial illustrators. Colorful scenes of dramatic action were replaced with a world that was subdued in color, drained of dramatic activity and enigmatic in meaning. While his subject matter was generally rural, it was a vision that was very much aligned with the existential anxieties of the nuclear age.

He was obsessed with minor details, of what you can learn from objects that are easily overlooked. Absence – what’s not in the frame – also played a big role in his work.

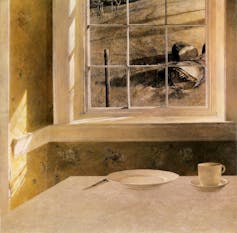

For example, Wyeth’s painting “Groundhog Day” shows a sunny dining room with no one in it. It’s actually a displaced portrait of his neighbor Karl Kuerner, who fought for the Germans in World War I. Wyeth once told me Kuerner was the most brutal man he knew.

It takes a moment to notice that in this room – even with its cheerful yellow wallpaper – something’s not quite right. Karl’s place setting doesn’t contain a fork or spoon. There’s only a sharp knife. By taking out the thing we would normally expect in a portrait – a human figure – Wyeth makes us pay attention to things we wouldn’t usually notice, such as a place setting.

In significant ways, we get a richer (and scarier) sense of Karl Kuerner’s character than if Wyeth had physically depicted him in the frame. (Many good filmmakers, including those who have carefully studied Wyeth’s paintings, like M. Knight Shyamalan and Terrence Malick, use a similar approach.)

The march of abstract expressionism

But by the 1980s, Wyeth’s work was being savaged by critics. He was thought of as an anti-modernist and a reactionary, a painter who had turned his back on the expressive techniques developed by figures like Matisse, Picasso and Jackson Pollock. To the critics, Wyeth was old-fashioned, someone constrained by outdated, 19th-century ways of seeing the world.

How did he become inflicted with what art historian Wanda Corn has called “the Wyeth curse”?

Clearly, he was a victim of some larger cultural and political shifts. It’s not unlike what happened in Stalinist Russia, when revolutionary heroes were purged and were quite literally painted out of history paintings. At some point Andrew Wyeth no longer had a place in the official history of modern art. He had to be painted out.

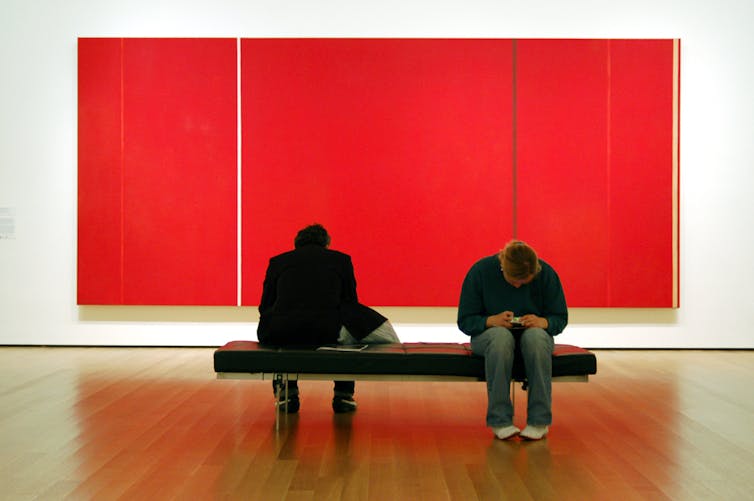

During this period, the battle lines of the modernist movement were hardening. Many notable art critics, led by Clement Greenberg, believed that modern artists had engaged in a sort of lockstep march toward modes of expression that rejected an identifiable subject matter. These new paintings were increasingly flat and abstract, concerned chiefly with the arrangement of unrecognizable shapes and forms.

It left no room for a painting of a girl sprawled in a field, with a rustic house looming in the background – however dreamlike the scene might appear.

The logic of this “modernist march” was never very strong, since the works of some key modernist figures such as Jackson Pollock have great pictorial depth and don’t look flat. And the outcome of this progression was surely not very interesting – a painting that would be entirely flat and would represent nothing.

Nonetheless, the critics had sharpened their knives. “Moving your eye” across Wyeth’s paintings, The New Yorker’s Peter Schjeldahl wrote, was “like sledding on dirt.” Critic Dave Hickey sneered that Wyeth’s palette was made up of “mud and baby poop,” while the Oxford Dictionary of American Art and Artists called him a “popular realist” with “little conceptual originality.”

Getting personal

There were other forces at play.

I suspect that there was resentment about Wyeth’s success at a fairly early date. The Museum of Modern Art was largely formed around its collection of paintings by Pablo Picasso. It must have irked the staff that a painting by a young American upstart quickly became the most popular painting in the museum.

A major turning point, however, clearly occurred in 1976. On the surface, it was one of Wyeth’s most triumphant years: He was awarded a one-man show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the first time this honor had been bestowed upon a living artist.

Henry Geldzahler, the museum’s curator of modern art, was originally slated to curate the exhibition. But he abruptly pulled out, with the director of the museum, Thomas Hoving, taking his place. In fact, there’s a backstory to why Geldzahler reneged. He had asked Wyeth to gift him a major painting, “River Valley.” The request went against basic standards of curatorial ethics, and Wyeth declined. In retaliation Geldzahler pulled out of the project and, according to Hoving, badmouthed Wyeth to his friends.

Whatever the exact cause, it was precisely around this time the New York art world – a surprisingly small place – decided that Andrew Wyeth was a pariah. It didn’t help that Wyeth sold most of his work through a network of dealers located outside New York. Notably, when the Museum of Modern Art celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1979, Andrew Wyeth wasn’t invited to the party, even though he had created the most famous American painting in the museum.

To this day, the museum exhibits a strange ambivalence towards Wyeth’s masterwork, “Christina’s World.” They refuse to lend it to major exhibitions – such as the centennial exhibitions of Wyeth’s work now appearing around the country – on the grounds that it’s too valuable to part with. But for years it was separated from the rest of the museum’s collection, and hung in places that demeaned it – by the escalator, in front of the restaurant and next to the entrance of a bathroom.

Wyeth today

A decade ago, a career-minded art historian would have avoided Wyeth. But in recent years, a number of gifted art historians have returned to Wyeth to reevaluate his legacy: Adam Weinberg, Timothy Standring, David Cateforis, Ann Klausen Knutsen, Alex Nemerov and Randall Griffey, among others.

The reasons for the uptick in interest are surely varied. But a central factor seems to be that Wyeth’s work is thoroughly in tune with what is being produced by adventurous young artists today. They’ve largely rejected abstraction as a vehicle, finding it unsuitable for the topics they want to address: body, gender, racial discrimination, politics, cruelty, mortality – the very issues which Wyeth addressed in his work.

While much contemporary art is in new media, such as video, rather than painting, the underlying message of Wyeth’s art remains very relevant. Art historians continue to argue about how to pigeonhole Wyeth within a terminology of visual styles. Was he a realist, a magic realist or a neo-realist?

My own view is that these labels aren’t useful. I believe he fits into a larger tradition of modernist creativity that goes beyond the medium of painting, one that’s also found in novels and movies – a tradition of attending to the overlooked. His influence – like that of his contemporary, Edward Hopper – has been most important and profound not in the realm of painting, but in poetry, literature and filmmaking.

He had no place in a world of art devoted merely to shapes and forms, and to nothing deeper. For this, his reputation suffered. Fortunately, he has again emerged as an original and challenging figure to a new generation of artists, critics and historians.