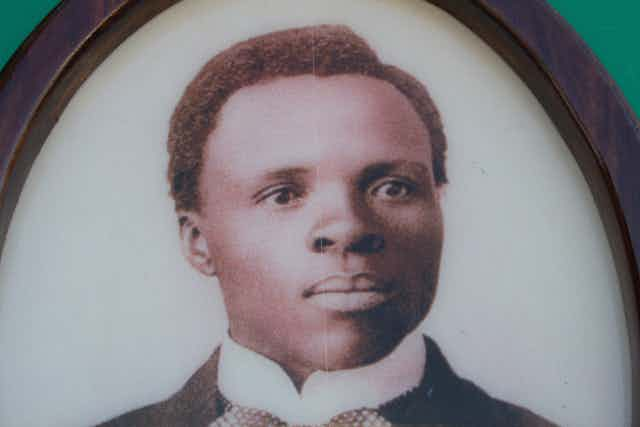

Over the last decade, inquiry into the life and work of South African writer, intellectual and politician Solomon T. Plaatje has been spurred by a series of hundred-year anniversaries.

In 2010 it was the centenary of the formation of that dubious political and geographical structure, the Union of South Africa, which would shape the focus of Plaatje’s many projects until his death in 1932. It was also in 1910 that he founded his second Setswana-language newspaper, Tsala ea Becoana.

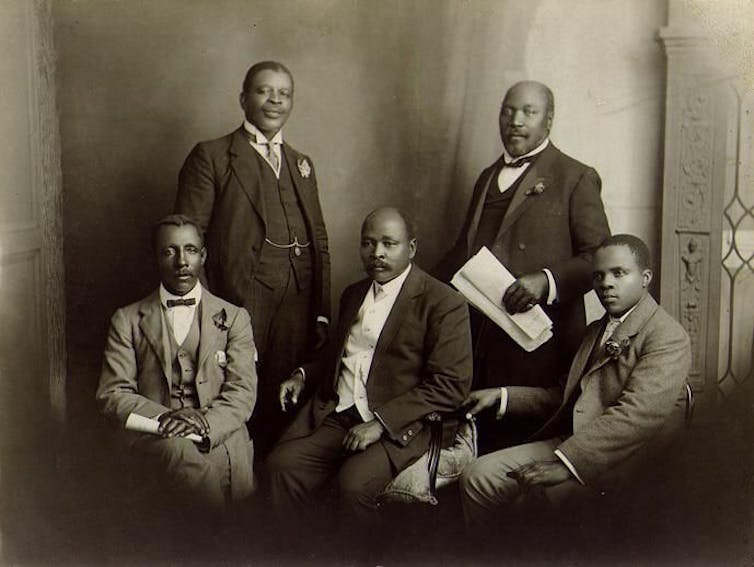

Two years later, Plaatje was one of the eminent group who formed the South African Native National Congress, which would later become the African National Congress (ANC). In 2012, when the ANC celebrated its centenary, Plaatje’s name was often cited, although he has been more readily associated with a cosmopolitan, erudite – “elitist”? – strand in the ANC that did not fit with the populist brand emphasised by the party in the shift from Thabo Mbeki’s presidency to Jacob Zuma’s.

There was another hundred-year anniversary in 2016, this time of the publication of Native Life in South Africa. The book was Plaatje’s seminal response to the passage of the Natives Land Act of 1913. This notorious piece of legislation set a traumatic tone for the dispossession, segregation and violent oppression that would characterise late-colonial and apartheid South Africa as the 20th century wore on.

Here was Plaatje in strident “Give back the land!” mode, an appealing figure to those advocating for more radical approaches to redressing the disenfranchisement of black South Africans.

The year 1916 is also significant in the field of Plaatje studies because it was when he contributed his short bilingual English-Setswana essay “A South African’s Homage” to the Book of Homage to Shakespeare.

Here again, we have the paradox of Plaatje writ large. The “Homage” signals his future undertaking as a translator of Shakespeare’s plays into Setswana. He saw this as complementary work to his wider promotion of the language. Yet his affinity for Shakespeare cannot be disconnected from his attachment to Britain and to its empire, his role indeed as an imperial apologist, which can seem difficult to reconcile with some of his other political and literary credentials.

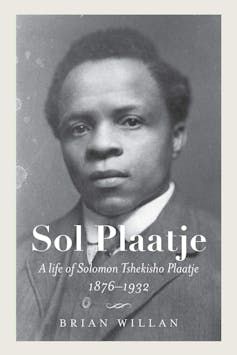

To make sense of this requires a deeper understanding of Plaatje’s historical context as well as his life’s trajectory, and the people, convictions, accidents and circumstances that shaped it. Happily, this is made possible by historian Brian Willan, who has chosen Plaatje as the main focus of his own life’s work and who knows his subject better than anyone else. Willan wrote a biography of Plaatje in 1984. The book seemed definitive until, in 2018, Jacana Media published his Sol Plaatje: A Life of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje, 1876-1932.

A magisterial biography

“Magisterial” is a word too often applied to biographies that don’t quite merit the moniker. But in the case of Willan’s book it is entirely apt. This may not be the final word on Plaatje. Nevertheless, it is a text to which all future scholars and researchers working on Plaatje will have to refer.

At almost 600 pages it is an encyclopaedic tome, documenting Plaatje’s life and times in rich detail. The true achievement of the book, however, is that it manages to do this in an engaging manner and with a prose style that – while never “chatty” – imagines a kind of conversation with the reader.

One can follow the chronological narrative, through 18 chapters marking out distinct periods in Plaatje’s astonishingly productive life. Alternatively one can dip into and out of its pages, navigating its riches via the index, or even flipping idly between phases and themes.

Fortunately, Willan is neither zealous nor jealous when it comes to his subject. His collaborations with other scholars have yielded fruit in various other Plaatje-oriented publications. In 2016, Wits Press published a collection of essays on Native Life co-edited by Willan, Bhekizizwe Peterson and Janet Remmington.

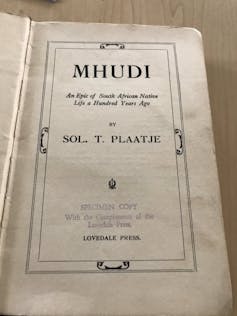

Mhudi gets a new collection

Later this year, Jacana will publish a similar collection, co-edited by Willan and fellow Plaatje biographer Sabata-mpho Mokae, focusing on Plaatje’s novel Mhudi. I am fortunate to be one of the contributors to this volume.

Mhudi appeared in 1930 after an exhausting 10-year battle to get it into print. So 2020 marks another centenary of sorts.

What are we to make of this novel, with its eponymous heroine and her husband Ra-Thaga, whose lives coincide with major colonial-era clashes in the first half of the 1800s?

It seems, by turns, to be an imperial romance and an allegory that is critical of empire; a naïve vision of interracial cooperation and a reminder that history is relentless in its cycles of violence.

Is it an affirmation of tribal tradition, or a feminist riposte to patriarchal culture? Is it a patchy experiment in need of an editor, or a genre-busting proto-postmodern pastiche influenced as much by oral narrative traditions as by the polyvocality of Shakespearean drama?

What is beyond question is the significance of Mhudi as the first novel in English by a black South African writer.

The next wave

The novel’s original publisher, Lovedale Press, sadly faces the prospect of closure. But it is encouraging to note that other independent publishers have committed their resources to keeping Mhudi current. Blackman Roussouw’s Strandwolf imprint has brought out a new edition. Jacana also has plans to publish another edition alongside Willan and Mokae’s critical volume on the novel.

It is to be hoped that, by the time we reach the centennial celebration of Mhudi being published by Lovedale (1930) and the centennial commemoration of the author’s death in 2032, the new wave of scholarship on Plaatje will have challenged readers to grapple with this enigmatic, protean polymath anew.