Prince Harry’s current secondment with the Australian Army, and the coverage it has received, reminds us of the imperial ties of old – and so does the forthcoming Gallipoli centenary.

As Anzac Day approaches we have been “bombarded” with memories, recollections, and re-imaginings of the Anzac experience at Gallipoli. Despite the recent burnishing of ties with Britain and the royal family, much of that is about defining us as distinctly Australian.

Gather round the flag

In reality, 100 years ago Australians and New Zealanders responded to the clarion call of the British Empire. There was no question as to where the loyalty of the overwhelming majority of Australians lay. They rallied around the British flag – Australia’s national flag until the Flag Act 1954 made the now ubiquitous blue ensign the Australian national flag.

Prior to that point Australians were more familiar with the red ensign, emblazoned with the southern cross and federation star, symbolising Australia as a subordinate part of empire. The blue ensign, while in circulation, was reserved largely for use by federal government and military institutions.

Back then Australian citizens were unquestionably British subjects. Britain dominated Australia’s trade and dictated its foreign policy. Even its defence policy was shaped by decisions made in London.

It was totally understandable that Australians would identify with Britain’s flag, the Union Jack, as their own. Such feelings would linger beyond the war, despite the profound damaging and divisive effect of the war on Australian society.

As Britain’s star waned, the Statute of Westminster of 1931 divested Britain of responsibility for foreign policy of dominions including Australia. But it was not until 1942 that Federal Parliament adopted its provisions, marking a fuller sense of Australian independence.

The Southern Cross era

The Flag Act 1954 finally made the Southern Cross-emblazoned blue ensign, not the Union Jack, the Australian national flag – although many military ensigns and “colours” remained based on the Union Jack for decades afterwards. Duntroon’s “colours”, for instance, only changed in 1973 to be modelled on the current Australian flag.

In the meantime, the Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948 made Australians not just British subjects but Australian citizens as well. Later on the Citizenship Act 1969 made it easier for non-British migrants to become citizens.

Britain’s accession to the European Community, the precursor to the European Union, in 1973 virtually ended the pretence of Australians still being British subjects.

Arguably, however, it was not until appeals to the British Privy Council ceased by virtue of the Privy Council (Appeals from the High Court) Act 1975 that Australia’s legal subordination to Britain ended.

In the meantime, Anzac Day waned in popularity as the Vietnam War ebbed. The “one day of the year” was an event that looked destined to die with the last veterans of Gallipoli.

Sometime later, Peter Weir’s 1981 movie Gallipoli added much impetus to the reinvention of Anzac as being about defining Australians not so much with Britain as against the Brits. The famous climactic and deathly charge was ordered by a man with a strong British accent, yet in real life the order was given by an Australian officer.

One hundred years on from the landings at Gallipoli, Britain’s Empire has long since passed, but Anzac Day is more popular than ever. In the absence of a climactic event such as a storming of the Bastille or a War of Independence Anzac Day has come to be a defining national event.

A flag for the next Anzac centenary?

Australian foreign and defence policy is now made in Canberra, not London. While many still claim British ancestry and ties with Britain remain strong, Australia is now a much more diverse community.

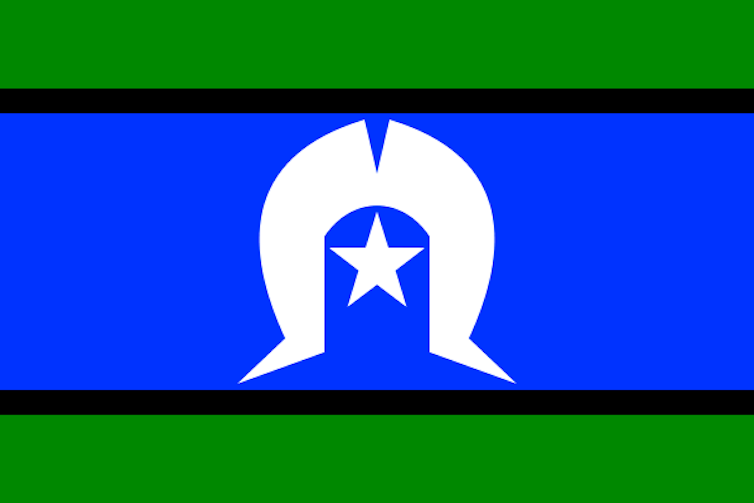

Additionally, the place of the first Australians has come to be recognised more fully. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flag flies alongside the blue ensign at federal government institutions around the nation.

But strangely enough the key national symbol, the Australian flag, lags behind.

American comedian Jerry Seinfeld once described the Australian flag as the British one on a starry night. For decades now Australians have been talking about finding a new flag that speaks to modern Australians. Dozens of designs have emerged but none have yet captured the public imagination.

Last year on The Conversation I suggested a design intended to foster reconciliation and inclusiveness while capturing the symbolic connections with Australia’s British colonial and Aboriginal heritage and its present multicultural diversity.

With feedback, the above, modified version has emerged. It incorporates the familiar Southern Cross, with its seven pointed stars and echoes of the Union Jack, with the red boomerang abutted by a band of white next to the dark blue (also reminiscent of Australia being “girt” by sea and beaches).

Together, the red, white and blue also echo the colours and stripes of the Union Jack.

The new design retains the federation star, but in yellow, and elevates it into the prominent top left corner. The yellow star overlaps the red and dark blue, echoing Aboriginal symbolism.

In the federation star, 250 black dots represent the 150 or so Aboriginal languages spoken today and the many languages spoken by migrants to Australia since 1788 – all inside the symbolic seven-pointed star of federation.

Not everyone may like this design. But as we reflect on the meaning of the centenary of Anzac it is appropriate to discuss our flag and consider alternatives. It seems an apt time to do so.