A speech in a play by Shakespeare or one of his contemporaries can be as short as a word or as long as several hundred, or anything in between. But what is the most common length?

There is an interesting new story emerging about the lengths of speeches in early modern plays. Staying away from Shakespeare himself for a moment, we can take Ben Jonson’s play Volpone (1607) and count the number of speeches and their lengths. The most common length is four words.

In the first scene of the play, Volpone asks if an entertainment was Mosca’s invention. Mosca says he will acknowledge his responsibility only if it has pleased Volpone, who says “It doth, good Mosca.” Mosca replies, “Then it was, sir.” Later in the same scene Corbaccio asks Mosca, “How doth your patron?” and “Does he sleep well?”

There are 1,412 speeches in Volpone and 166 of them (12%), are just four words long. There are more speeches of this length than any other length. Four words is, as we say, the “mode”.

The next most common length is five words: 9% of Volpone’s speeches are this length. Of the other 16 Jonson plays, 12 also have a speech length mode of four. The four plays that don’t are Every Man in his Humour, with a mode of five, Every Man Out of his Humour and Bartholomew Fair with a mode of six, and Tale of a Tub with a mode of nine.

It’s not just Jonson; it’s everybody. After 1602, four-word speeches are the most common kind across all the early modern plays that survive.

Curiously, just five years earlier, four-word speeches were very rare: the mode was nine-word speeches. The change happened in just five years, affected every writer, and we don’t know why.

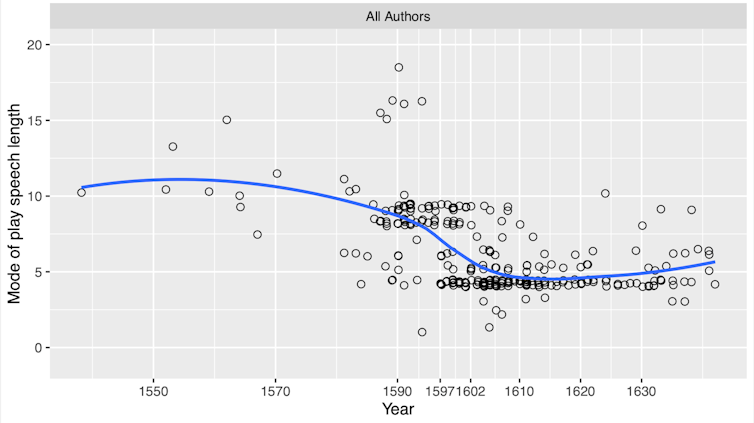

Here we see the modes of speech lengths for 273 early modern plays, shown as circles. From a slow start with few plays, the London theatre industry took off in the late 1580s and early 1590s and we see a concentration of speech-length modes around nine or ten. Then, from 1597 to 1602, a mode of four or five overlaps with modes of eight or nine, then after 1602 the mode of four predominates.

The pattern is not absolute: we see plays from before 1597 with speech-length modes smaller than ten and plays from after 1602 with modes greater than four. But the clustering around ten and four is visible to the naked eye. Moreover, we can quantify how strong that clustering is. Well-established statistical measures tell us to expect patterns like this only very rarely when mere chance is at work in the data.

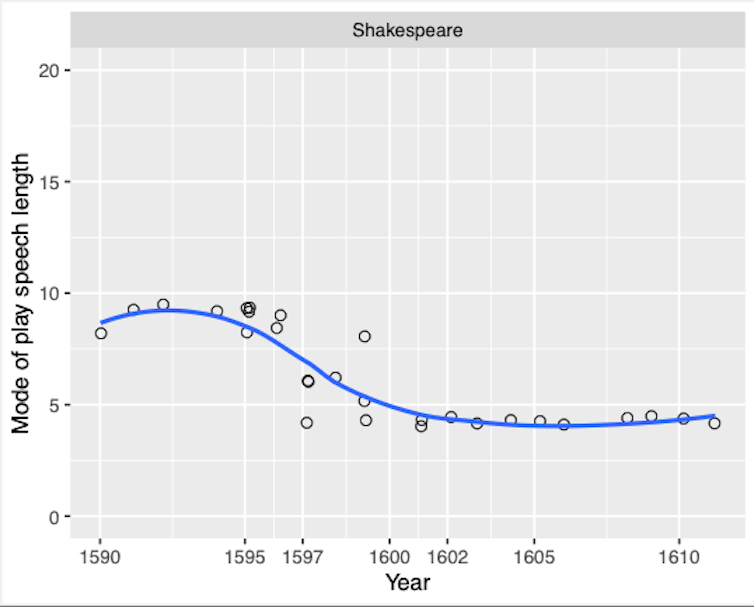

If we look just at Shakespeare plays, we find him doing what everyone else did: shifting from favouring nine-word speeches to favouring four-word speeches around 1597-1602 and never going back.

Change in mode

The credit for first seeing this pattern of change in modes of speech length goes to Hartmut Ilsemann, who published about it in 2005. In 2007, MacDonald P. Jackson showed that the change in mode in Shakespeare was more progressive than had been suggested by Ilsemann, who thought it happened virtually overnight in 1599.

Then in 2019, Pervez Rizvi counted speech lengths in a much larger corpus, extending the analysis to Shakespeare’s peers. He confirmed the change from a mode of nine words to a mode of four words in Shakespeare, while showing that this is not peculiar to Shakespeare. This was evidently a pattern shared across the drama of the time.

These are important findings. Even nine words seems a short speech. Most literary-critical commentary focuses on longer speeches where thoughts, arguments and narratives are given fuller expression. No one before Ilsemann had identified a collective change to yet shorter speeches over the period.

It is also unexpected to find Shakespeare, who is generally assumed to be exceptional among his peers, participating in this change, following the collective pattern exactly, in the same direction, at the same time, and to the same degree.

In an article just published, we have confirmed the change in modes of speech length and explored the possible effects of other confounding factors, such as genre, author, theatrical company, and proportions of verse and prose. We find that these factors make no difference: the change is general and all that matters is the date of a play’s composition.

We show that the transition period can be defined as 1597 to 1602 and that there are subsidiary modes at 16 and 24 words, especially apparent in plays with high proportions of verse, suggesting an underlying unit based on the iambic pentameter line, which generally has eight or nine words.

There is no doubt that all those writing these plays obeyed some unspoken imperative and moved collectively to shorter speeches.

Read more: Shakespeare's First Folio turns 400: what would be lost without the collection? An expert speculates

But why?

The most important question remains: how best to understand the forces behind this change?

Ilsemann suggests that the explanation is the move of Shakespeare’s company to the Globe Theatre in 1599. Shakespeare was suddenly able to control the staging of his plays and was able to follow an artistic preference for shorter speeches.

This is unpersuasive, since conditions at the company’s previous venue, the Theatre in Shoreditch, were much like those at the new venue and Shakespeare’s role as playing company shareholder and chief playwright was unchanged. In any case, the change was not instantaneous and not confined to Shakespeare.

Rizvi, following a suggestion by Jackson, links the change in mode to a new propensity in Shakespeare to divide verse lines between two speakers – where part of the metrical line is spoken by the first speaker, and part spoken by a second or even a third. This shift to more shared lines, as Rizvi and Jackson note, was discussed in much earlier books on Shakespeare’s versification by Marina Tarlinskaja (1987) and George T. Wright (1988), though neither of these discussions mention any general change over time in the length of speeches.

This is another spectacular change. Only around 2% of all lines are shared between speakers in Shakespeare’s earliest plays, but shared lines became more common in his middle period, and commoner still at the end, with the last plays averaging over 15%. In Antony and Cleopatra, it reached 18%.

Our suggestion is that the playwrights learned progressively from one another how to represent more closely the speech lengths of everyday exchanges and found that audiences responded well to these. As the heritage of early modern English drama grew, playwrights understood the special properties of the medium better. Their styles moved away from an allegiance to writing and towards the dynamics of everyday speech.

Another way to think of this is offered by the Russian literary scholar Boris Yarkho (1889-1942). Yarkho may well have been the first to consider the length of speeches in plays in a systematic way. He proposed an “index of liveliness”, being the ratio of the number of speeches to the total number of lines in a play. He calculated this index for the comedies and tragedies of the 17th-century French playwright Pierre Corneille, the comedies having a higher index because of their shorter speeches.

The move from a mode of nine words to a mode of four represents a shortening of the average speech, and thus a move to more “lively” drama in Yarkho’s terms.

Read more: Ignore the doubters: here's why Christopher Marlowe co-wrote Shakespeare's Henry VI

Pauca verba

We have no record of any dramatist or playgoer reflecting on the shortening of average speech lengths; our only knowledge of it comes from counting the words in the plays for ourselves. But it might be reflected in phrases that Shakespeare gives his characters.

The Latin word “pauca” occurs seven times in Shakespeare. In The Taming of the Shrew, Sly brushes off the Hostess, who throws him out of her tavern with “paucas pallabris”, which is a kind of Latin-Spanish hybrid meaning “few words”.

In Love’s Labour’s Lost, Holofernes recites the proverb “Vir sapit qui pauca loquitur”, which is Latin for “That man is wise that speaketh few things or words”. About four minutes of stage time later, Holofernes cuts off any refusal of his hospitality with “Pauca verba” – Latin for “few words”.

In Much Ado About Nothing, Dogberry invokes “paucas pallabris” using just its second word, in the form “Palabras”, to shush Verges. In Henry V, Pistol silences himself to cut off his quarrel with Nim by saying “pauca”. And in The Merry Wives of Windsor, Evans tries to get Falstaff to moderate his tongue with “pauca verba”. A few seconds later, Nim picks up the phrase and repeats “pauca, pauca”.

With the exception of The Taming of the Shrew, which was written sometime between 1582-1593, these are plays from the narrow period we have identified when dramatists collectively opted for fewer words. Might Shakespeare have unconsciously registered the change in this bit of Latin?