Burning Down the House, curated by Brit Jessica Morgan, marks the 20th anniversary of the Gwangju Biennale, currently showing in Gwangju, a city in the south-west of South Korea.

Despite being one of the youngest events on the ever-expanding global biennial circuit, Gwangju has quickly become one of the most respected. And, with visitor numbers to rival the Venice Biennale, it is one of the best attended as well.

Democracy and art in Korea

The Gwangju Biennale was founded in 1995 to commemorate the pro-democracy protest and massacre now known as the Gwangju Uprising.

The Uprising began on May 18, 1980, when students assembled to peacefully protest the inauguration of yet another military strongman, Chun Doo-hwan, as Korea’s new president. Within nine days at least 240 protesters had been murdered by Korean Special Forces. Hundreds if not thousands more were beaten and injured, and more than 1,000 arrested in the aftermath.

While the Uprising was condemned by President Chun as an unlawful rebellion, it prompted a national and (eventual) international outcry that critically destabilised his new government. In so doing it also provided a foundation for, and powerful symbol of, the democratisation movement that would triumph by the end of the decade.

Artist boycott

Those political origins have remained at the foreground of the Biennale since its inception, and have provided it with a strong local context that runs against the grain of the place-less spectacle that characterises so many other large-scale international art events.

But this democratic foundation was tested even before Gwangju 2014 opened, when a painting by veteran political artist Hong Seong-dam was withdrawn from the satellite exhibition Sweet Dew – After 1980 at the nearby Gwangju Museum of Art.

Hong’s painting Sewol Owol (2014) linked the current Korean government’s role in, and response to, the catastrophic Sewol ferry disaster in April with that of the Gwangju Uprising itself. The withdrawal of his work came following pressure from the Gwangju Metropolitan City Council, which was itself allegedly pressured by the Federal Government led by Park Geun-hye, who Hong had depicted as a grotesque puppet.

When news of the decision broke, numerous artists withdrew from the show, several others pointedly obscured their work with anti-censorship messages, a key loan was cancelled and the respected president of the Gwangju Biennale Foundation, Lee Yong-woo, resigned.

Burning Down the House

There was no sign of further political interference when the Biennale proper opened on September 5. Indeed, Burning Down the House trenchantly foregrounds Korea’s tumultuous past. And, in a country that has been repeatedly razed and rebuilt throughout history, Morgan’s theme of “burning and transformation […], obliteration and renewal” is particularly resonant.

Such a direct curatorial address is also welcome at a time when the rationale of so many other biennials, such as the recent Biennale of Sydney, are so broad or oblique as to verge on the nebulous.

Morgan’s curatorial remit is apparent immediately upon stepping on to the Biennale Plaza. Here, Englishman Jeremy Deller’s giant, tromp l’oeil octopus smashes its way out of the building, while Sterling Ruby’s sculptural incinerators smoulder menacingly beneath.

Alongside the incinerators sit two shipping containers, part of the work Navigation ID (2014) by Seoul-based Minouk Lim. Although seemingly innocuous, a glance through the containers’ windows reveals their shocking cargo: unidentified human remains.

Inside the Biennale hall a dual screen video elaborates the presence of the bones outside. It charts the artist’s work with community groups to bring descendants of those disappeared by the Korean government during the Korean War together with the mothers of those killed during the Gwangju Uprising.

Together, the two groups visit the site of a recently uncovered mass grave and then accompany the excavated bones to the Biennale, all the time sharing their painful personal stories.

By bringing two generations together who faced state-sanctioned injustice and bereavement in the pursuit of political visibility, Minouk’s work is a jaw-droppingly brutal yet empathetic act of historical solidarity.

It is also one of the most extraordinary works of community engaged public art in memory. Indeed, the impassioned integrity of Minouk’s work, combined with Morgan’s curatorial chutzpah, makes the political aspirations of so much contemporary art and curatorship seem basely opportunistic by comparison.

Inside the Biennale proper the theme of fire and destruction continues to manifest in various ways.

Sometimes it is literal, as in the defamiliarising juxtaposition of historic work by French and Indian artists Yves Klein and Anwar Shemza, both of whom actually painted with fire.

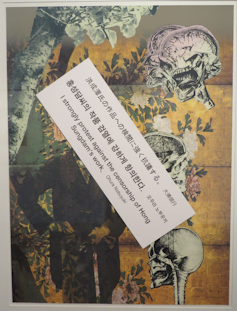

Sometimes it is figurative, as in the remarkable charcoal and monoprint mural by Romanian Mircea Suciu, Dust to Dust (2013), that traces a fiery history of revolution and war across the 20th and 21st centuries but refuses to reconcile its constitutive parts.

And sometimes it is social, as in the rousing film The Uprising (2012) by Brazilian Jonathas de Andrade, in which the alienated labour of horse-drawn transport is momentarily returned en masse to the Brazilian city of Recife to ecstatically but dangerously disrupt everyday life.

While the show is largely characterised by unfamiliar curatorial choices (either of artists or particular works), the points at which it falters are those where a well known (usually Western European) name appears to have been expediently and unnecessarily shoehorned into the program.

Most notable in this respect is the anti-climactic final gallery where the show concludes inexplicably with M.2602 (Fitzcarraldo) (2014), the latest instalment in French artist Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s series of impersonations of 19th and 20th century fictional characters planning an as yet unrealised opera.

A destructive energy spills out of the Biennale halls in further interventions at the nearby Gwangju Folk Museum and Spiral Pavillion in Jeongju Park. It also connects with the ongoing Gwangju Folly project, where architects are invited to make permanent interventions on key historic sites across the city including, among others, those of Japanese imperial atrocities.

The Gwangju Biennale is a timely example of how biennials, when curatorially anchored in one place over time, can provide a powerful forum for the perpetual recall and reanimation of specific histories of our time.

Burning Down the House – Gwangju Biennale 2014, Gwangju, South Korea is showing until November 9.