The large collection of paintings and drawings found in the Munich flat of the 80-year-old recluse, Cornelius Gurlitt, which came to wide public attention earlier this month, raises serious moral and legal questions.

How should governments and representatives of families of Jewish Holocaust victims deal with the legacy of the Nazi period?

Gurlitt is the son of an art dealer who sold works of art for the Nazis. Many of the works that passed through his hands had been classified by the Nazis as “degenerate art” and confiscated from museums and private collections.

Other artworks came from forced sales by Jewish families at bargain basement prices. In the 1930s, the Nazis made a tidy sum by selling these acquisitions in the world art market. The elder Gurlitt helped them do it.

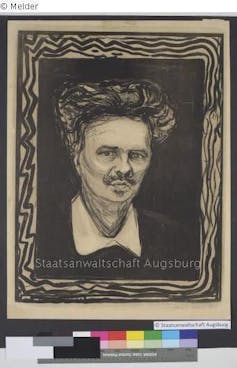

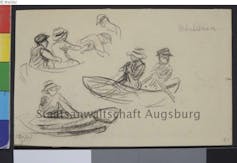

By means not yet explained, Gurlitt ended up with a personal collection of more than 1,000 paintings and drawings, including works by Matisse, Picasso, Chagall, Gauguin, Liebermann, Beckmann and Kretschmar.

A special task-force set up by the German Government estimates at least 970 of these were originally stolen by the Nazis. The origin of some may never be discovered.

These works of art eventually passed into the hands of Cornelius Gurlitt, who kept them hidden in his flat. Gurlitt zealously protected his horde, allowing no visitors and giving no hint to anyone about the existence of his vast collection.

The collection was discovered by accident when he came under suspicion for tax fraud. Almost two years have passed since tax officials raided his flat. News of what they found was only made public when the German magazine Focus reported on the trove on November 3.

Gurlitt has not given up his struggle to get his whole collection back. In a recent interview with the German news magazine Der Spiegel, he insists he and his father did nothing wrong.

Indeed, he claims his father saved works of art that would otherwise have been destroyed, lost or taken away by Soviet invaders. The paintings rightfully belong to him, he said, adding: “there is nothing I have loved more in my life than my pictures.”

Ownership rights

The legal issues are tangled. A lot of time has passed. Most of the owners of works taken by the Nazis are now dead. In any case, there is no proof the elder Gurlitt stole any of the pictures.

On the other hand, public opinion since the 1990s has come to favour claims of heirs for the return of art works stolen by the Nazi regime from their parents or grandparents. Some museums have been required to give back pictures that were originally stolen.

Does Gurlitt have a moral case for having the pictures returned to him? Does his apparent innocence, his long possession and his obvious love for the pictures give him a right to possession?

There are two reasons for objecting to his attempt to defend his ownership rights.

The first is that he is not really innocent. He did not steal the pictures, but the fact he kept them a secret suggests he knew that the dark cloud of Nazi crimes overshadowed his right to possession. Despite this, he made no attempt in all the years that he had the pictures to enquire about their origin, to contact those who might have owned them or get help in finding them.

The second reason against his continued ownership is the nature of the crimes that Nazis committed when they robbed Jews of their possessions. The Nazis did not merely persecute individuals. They wanted to destroy Jewish families.

Genocide is not just a matter of killing a lot of people. Its aim is to wipe out family lines and thus the future of a whole people. Robbing families of their possessions was just the beginning.

The crimes Nazis committed when they robbed, persecuted and killed Jews were crimes against families as well as individuals. That means restitution can be owed to surviving members of these families.

Anne Webber, co-chair of a commission that helps families retrieve artwork stolen by the Nazis, thinks that restitution of lost possessions is a matter of justice:

Hitler’s project was to erase Jews from history. So to treat claimants as if history and circumstances of loss were of no consequence can be like a re-run of that history.

The German task-force investigating the Gurlitt case recognises the obligation of returning paintings to the heirs of owners. But it also intends to return some of the pictures to Gurlitt. It should not do so without a thorough attempt to find original owners.

But perhaps these officials are right to assume that Gurlitt is entitled to keep pictures when original owners cannot be found.

If so, he can live out the rest of his lonely life with some of the things he loves.