The priorities and themes of the 10th BRICS Summit, ranging from peacekeeping to collaboration around the 4th Industrial Revolution, provide a number of issues that summit leaders say they want to pursue.

The summit in Johannesburg is the culmination of regular meetings held by the foreign ministers of Brazil, China, India and Russia since 2006. The BRICS political bloc was institutionalised as a platform in Yekaterinburg, Russia, on 16 June 2009. South Africa officially joined in 2011.

Reconciling domestic interests and priorities with international obligations will remain a fundamental focus for this meeting. But perhaps the more critical question to ask is how the bloc is going to strengthen its role and agenda in an international order that is characterised by fragmentation and uncertainty.

Over the past 10 years, the BRICS partners have launched a number of initiatives aimed at providing additional and different capabilities to global, political, and economic governance structures. One of its projects has included creating the New Development Bank. So far the Bank has initiated funding to the value of US$3.4 billion at the end of 2017 to member countries.

In addition, BRICS has created the Contingency Reserve Arrangement, aimed at ensuring liquidity for member-states when they’re confronted by short term balance of payment crises.

With these institutions in place, the 10th summit provides the opportunity for the five countries to reflect on the bloc’s practical relevance and its future footprint.

Scepticism around the coherence of BRICS as a functioning group persists. But it’s safe to bet that the five countries won’t regress in their obligations. To retreat now would be a colossal admission that the cynics were right all along.

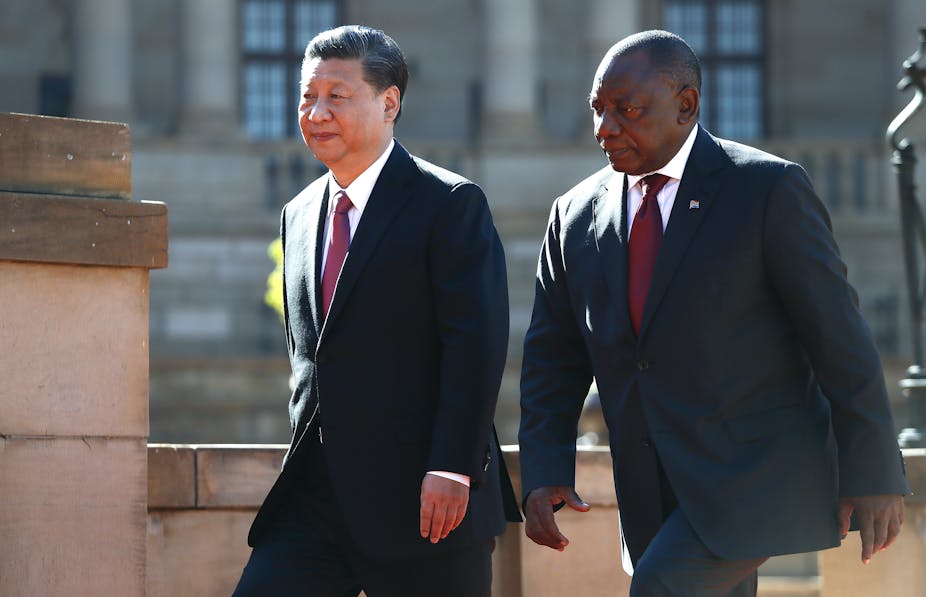

The BRICS bloc will also want to assert its authority on the back of the growing uncertainties in global political affairs. Two of its members, China and Russia, are caught in the cross hairs of a belligerent US. This makes it a particularly important time to emphasise and cement the role of BRICS.

What’s next for BRICS?

BRICS should by no means be romanticised. It is, by its very nature, an imperfect construction given the size and scale of its member states.

Interesting new nuances are affecting the positioning of China, India, and Russia within the BRICS bloc. These include two factors: new alliances between the five countries, and China’s massive Belt Road Initiative, President Xi Jiping’s re-configuration of channels that connect China with Asia, Africa and Europe.

The BRICS bloc also comprises of sub-groupings that play a significant role in influencing internal loyalties and strategic interests within the group. There is the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation which was formed in 2001. It is seen as an intergovernmental organisation that deals with energy and security made up of China, Russia and six central Asian republics. It’s been characterised as the counter weight to US influence in Central Asia. Other commentators are identifying it as the counter balance to the G7, a bloc made of the US, Germany, France, Italy, Canada, Japan and the UK.

Then there is the India, Brazil and South Africa trilateral cooperation bloc. This was established in 2003 as a South-South cooperation platform.

The cooperation between Russia, India and China has also become prominent. In April 2016, the foreign ministers of Russia, India and China met to further their cooperation around a global governance agenda. Similarly the relationship between China and Russia is strengthening. All of this will inform how BRICS develops from here on out.

The Belt Road Initiative has already sparked disagreement. In the run-up to the 9th BRICS Summit held in China, the Indian delegates attending the academic forum in Fuzhou were steadfastly opposed to

docking the Beijing led Belt and Road Initiative with the grouping in the future.

Another source of difference is around a possible extension of the BRICS membership base through the BRICS Plus concept. At the 2013 Durban Summit, South Africa initiated the BRICS Outreach Partnership, a channel of inclusion for key partners across the African continent.

In 2017, China remodelled the BRICS outreach partnership into the BRICS Plus which has a more expansive outlook within a broad spectrum of actors from emerging markets and the developing world. The shift of the traditional outreach partnership into the BRICS Plus could be interpreted as testing the waters for the possible expansion of BRICS membership.

But India seems to be uncomfortable with the BRICS Plus concept, in particular a reconfiguration of the grouping stacked in favour of Beijing.

A gap to lead

While the collective identity of the BRICS bloc is still being tested, the prevailing cracks in the global system present opportunities for it to assert and strengthen its position. It can do so by upholding the principles of the liberal multilateral trading arrangements which the US seems to be dumping.

The significant question will be: how and to what extent will the BRICS take the next step in underwriting the rules of the game in an international order that is seeking leadership and direction?