One consequence of the High Court’s 2020 judgement that caused the National Archives to release Sir John Kerr’s correspondence with Buckingham Palace was that the royal correspondence of other governors-general also had to be released.

More than a year and a half later, after the archives scoured every document for an embarrassing detail that could be redacted, these letters have now been made public.

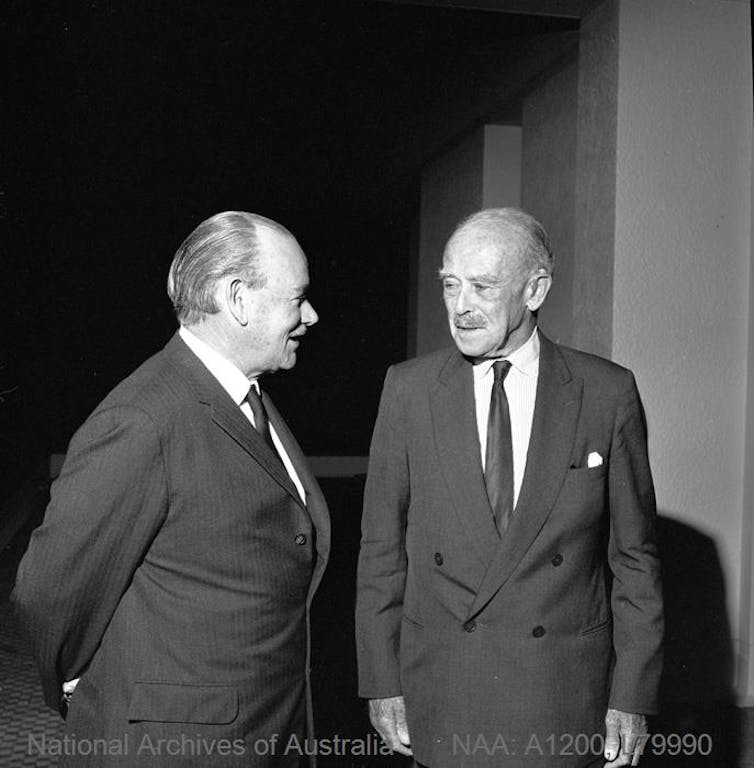

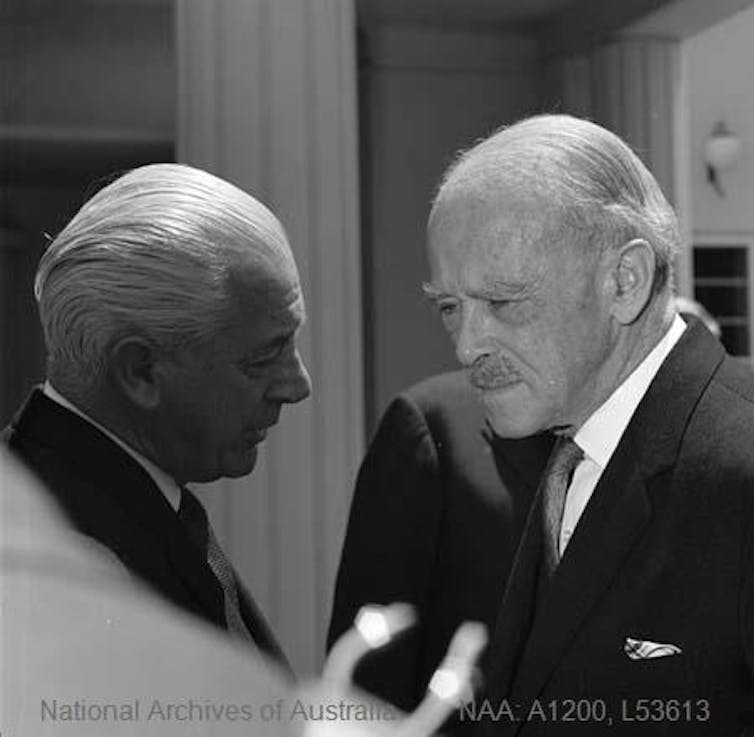

They cover the terms of four governors-general: Lord Richard Casey (1965-69), Sir Paul Hasluck (1969-74), Sir Zelman Cowen (1977-82) and Sir Ninian Stephen (1982-89).

What is most remarkable about the letters is how similar they are to Kerr’s correspondence with the palace.

All the features that critics have picked on as unprecedented and inappropriate – the detailed political analysis, the obsequious deference, the focus on formalities, the discussion of reserve powers – are common features in the correspondence of Kerr’s predecessors and successors.

Read more: 'Palace letters' show the queen did not advise, or encourage, Kerr to sack Whitlam government

Frank political reports

This is unsurprising, because the palace encouraged the governors-general to write with “complete freedom and frankness” about political affairs in Australia and anything affecting the monarchy and the powers or status of the governor-general. This keeps the monarch well informed about her various realms.

Each governor-general, therefore, gave regular detailed and often quite critical reports on the political controversies of the day and the likely outcomes of elections.

Kerr’s analysis was, indeed, quite tame compared with that of his predecessors, Casey and Hasluck, who had stronger political pedigrees.

Flattery and formality

To today’s eyes, the correspondence is often cloying and obsequious in its formality and deference, but this was standard for the time. The letters include many professions of “loyalty” and “devotion” to the monarch and every royal tour is a “great success” and “very well received”, especially by the “plain folk”.

Hasluck, in his comment about a prospective first meeting of Queen Elizabeth and Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, said:

If I may venture to say so, with due humility and respect, the wisdom and experience of Her Majesty will find here an opportunity to help make a promising Prime Minister into a better one and I believe he will prove responsive to Her counsel and guidance.

Not even Kerr could have topped that for flattery.

The excess of admiration also flowed the other direction. Governors-general are constantly praised for their “wisdom”. Deference is also given to their greater knowledge and understanding of the local political situation.

Letters from the palace praise and support the governor-general – they never criticise or instruct.

The focus on the formalities was strong throughout. This is because the monarchy represents itself to the people through such courtesies, pomp, honours and ceremony. Hence, a large part of the correspondence concerns changes to the oath of allegiance, the national anthem, the vice-regal salute, the royal anthem and the honours system.

Hasluck did his best in 1972 to dissuade the prime minister, William McMahon, from initiating a search for a “national song”, fearing it would replace “God Save the Queen” as the national anthem.

In 1984, Stephen was still having robust discussions with Prime Minister Bob Hawke about the use of “God Save The Queen” and the vice-regal salute. He even changed an Executive Council Minute by hand so that groups such as the Country Women’s Association and the RSL could continue to sing “God Save the Queen” without being in the presence of royalty.

Read more: Explainer: what is the 'palace letters' case and what will the High Court consider?

The reserve powers

But what about the reserve powers, which allow a governor-general to act without, or contrary to, ministerial advice? Was it unprecedented or inappropriate to discuss their nature and hypothetical application? No, because the others did so, too.

Hasluck, for example, discussed what would happen if the prime minister, Sir John Gorton, was defeated in a vote of no confidence in 1970 (which had been a real prospect) and then requested the dissolution of parliament and an election.

Hasluck said he would have felt bound to ask whether it was impossible for Gorton to carry on the government without an election, and whether the governing parties might be able to continue to govern under a different leader.

Hasluck wanted to be satisfied all possibilities of forming a government without an election had been tried before granting one. If not, he would exercise his reserve power to refuse a dissolution and appoint a new prime minister. Hasluck said he had put down these thoughts on paper

so that Her Majesty may be aware of the way in which I interpret my constitutional duties.

He was not alone. Stephen also reported his views on his reserve power to refuse advice to hold a double dissolution election and made Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser come back with additional advice before he agreed to grant one in 1983.

Hasluck exercised a reserve power by refusing to sign an Executive Council Minute approving a US defence science base in Australia just 12 days before the 1969 election.

He deferred acting because it would breach the caretaker conventions. He only signed the papers after the Coalition won the election and wished to proceed.

As for the governor-general consulting the chief justice of the High Court on legal matters, this again was shown to be well precedented.

Casey, for example, consulted Chief Justice Garfield Barwick after the presumed death of Prime Minister Harold Holt in 1967 and also, more bizarrely, on whether a satirical magazine that ran a spoof interview with Prince Philip could be prosecuted under the Crimes Act.

A snapshot of Australian history

The letters of the governors-general provide a fascinating snapshot of political history. They add context to our understanding of the governor-general’s office and the relationship between the monarch and Australia. Seeing only Kerr’s correspondence led to distorted interpretations. Reading it in the context of his predecessors and successors gives a much more accurate picture.

While many of the reports are quite candid and frank, their release after so many years is hardly damaging, and the efforts to keep them secret for so long are again shown to be absurd.

Australia’s history should not be locked up forever in hermetically sealed boxes – it belongs to all of us and it is good that we can finally see some of it.