Land-clearing laws are being fiercely debated in both Queensland and New South Wales. These two states are responsible for the majority of cleared land in Australia’s recent history.

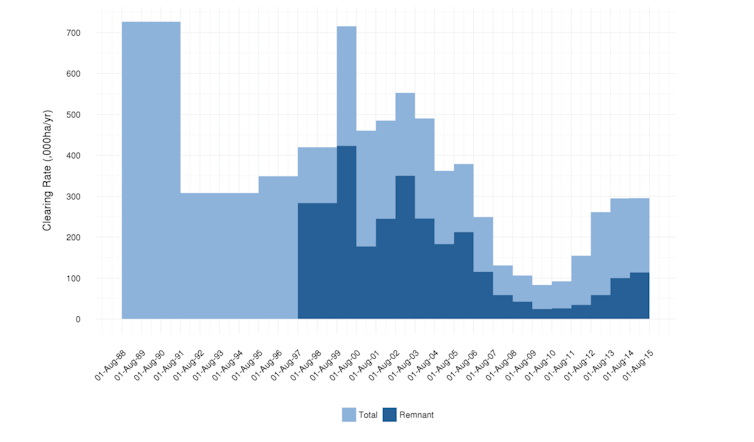

The latest assessment from Queensland shows that 296,000 hectares of vegetation was cleared in 2014-15. More than a third of this is remnant vegetation that has never been cleared before.

To put this in perspective, around 580,000ha of forest was cleared in Brazil over the same time. While this is twice the area recently cleared in Queensland, it’s worth remembering that the rate of clearing has been much higher in the past, before legislation first came into effect more than a decade ago.

In NSW, around 23,000ha of vegetation has been cleared for cropping and pasture since 2010 and 59% of this is “unexplained”: clearing of regrowth vegetation, for routine agricultural management, exempt from legislation, or illegal.

The science is clear about the detrimental effects of land clearing on the climate, native wildlife and soil health. More than 400 international and Australian scientists recently signed a declaration highlighting their concern about the rate of forest loss in Australia. Such a degree of coordination between scientists hasn’t been seen since the original Brigalow Declaration in 2003.

How to address effectively the issue of land clearing remains fiendishly complex. Land clearing is such a political issue in Australia, as any policy changes affect many people in the community.

Recently proposed policy changes in both NSW and Queensland have proved to be contentious. Farmers and environmental groups in NSW have highlighted concerns with Premier Mike Baird’s proposed Biodiversity Bill. Last week, Queensland farmers unhappy with Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk’s proposal to re-strengthen land-clearing laws marched on Parliament House to protest the changes.

Australia has the ability and resources to reduce land clearing, if it chooses. How might we do it?

1. Stop the policy flip-flop

Since the 1970s, state and federal governments have introduced at least 40 regulations, incentive schemes and policy frameworks related to vegetation management. One of the key concerns reported by farmers is the “policy flip-flop”, in which successive governments introduce land-clearing laws that are strong, then relaxed, then strong again.

These frequent policy changes create huge uncertainties for farmers who want to make long-term business decisions. It also means that government resources are almost constantly devoted to designing new policies, rather than ensuring that existing policies are effective.

For land clearing to be controlled over the long term, more resources need to be allocated to encouraging, supporting and enforcing compliance with vegetation laws.

2. We do need regulation

Strict controls on vegetation clearing are often deeply unpopular with landholders. Relying too heavily on regulation can also lead to poor compliance and unnecessary costs. However, the reality is that some form of “top-down” regulation will always be needed to protect native vegetation in the long term. History has shown this to be the case.

Before it introduced land-clearing controls in the 1980s, the South Australian government provided landholders with financial incentives to conserve native vegetation. Unfortunately, clearing did not decline, as the scheme attracted only landholders who had already planned not to clear their vegetation.

A combination of regulation and long-term financial incentives is needed. Unfortunately, most incentive schemes are small compared to the value of farming, and are usually short-term – such as the five-year package announced as part of the NSW Biodiversity Bill.

3. Put a price on carbon

Encouraging long-term protection of native vegetation requires a market signal, and a carbon price would do this. The federal government’s Emissions Reduction Fund doesn’t provide bang for buck, and there’s evidence it is being used to conserve vegetation that would never have been cleared anyway.

Increased clearing in Queensland may have effectively cancelled out the carbon emissions saved under the Direct Action plan.

We know it is possible for carbon farming to be a win-win for the climate and wildlife. Many parts of Australia need only a moderate carbon price to make restoring and conserving native vegetation a profitable business enterprise. Long-term policy certainty and a consistent message from federal and state governments are needed.

4. Self-regulation where appropriate

Over the past decade, there has been trend towards self-regulation of vegetation management. For low-risk activities, it makes sense for landholders to be able to manage vegetation by simply notifying the government, rather than applying for a permit. This reduces costs for the landholder, and frees up government resources to monitor for compliance and regulate high-risk clearing (where the proposed area to be cleared is large, or may impact threatened species habitat).

Self-assessable vegetation clearing codes been introduced in New South Wales and Queensland, but have been criticised for enabling broad-scale clearing. Clearly, more work is needed here to get the balance right between managing environmental risks and minimising regulation costs.

5. Rebuilding trust

The debate over land clearing in Australia is so heated and highly polarised that it can be difficult to see a path forward. There appears to be very little trust between some landholders and state governments, leading in some cases to tragic consequences.

Providing some long-term policy certainty and consistency between federal and state government messages will go a long way in helping to rebuild mutual trust. A price on carbon would allow landholders to generate income from sequestering carbon alongside farm businesses.

Reducing regulation in circumstances where the environmental risks are low while ensuring resources are devoted to supporting compliance can reduce costs for both landholders and governments without jeopardising the environment.

Australia needs to get land-clearing policy right, and soon. While the debate rages on, more vegetation is lost – and ultimately we all lose.