A Federal Court decision to allow gene patents could open the way for existing patents to be enforced more strongly in Australia, according to an expert in intellectual property.

Biotechnology companies will be permitted to hold patents on genes in Australia after a decision by the full bench of the Federal Court. The ruling upholds a Federal Court decision in February, 2013, which was under appeal.

The court found companies can hold patents in Australia over isolated biological material, in this instance, fragments of DNA that are defined as BRCA1 gene mutations, said adjunct professor of law at Murdoch University Luigi Palombi.

The BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations predispose women with a familial history to developing breast and ovarian cancer.

It’s unclear what impact the decision will have in Australia because the patents have not been strongly enforced here. Melbourne-based Genetic Technologies, which holds the local licenses for the patents, has faced a public backlash when it has tried to enforce the patents.

Genetic Technologies and Myriad Genetics have previously said the patents were a gift to the Australian people.

Associate Professor Clara Gaff, who formerly worked as a counsellor for people with or concerns about hereditary cancer said that people who provide genetic testing and patients are likely to be concerned if this means that testing becomes more expensive and unavailable to them in the way that’s currently available.

“People see genes as essential human characteristic rather than something that’s invented and that’s maybe where some of the subtleties come in,” she said. “People may have different views on that depending on what their perspective is.”

“So researchers could see the benefits of patenting to enable them to be innovative and to enable funding for experimentation, while patients who want tests and don’t want to have any restrictions around that, have fears that patenting might limit that.”

Professor Palombi noted that the research exemption for the patent was so narrow that only pure research was permitted.

“Patients who want tests might fear patenting would restrict their access,” Associate Professor Gaff said. “But to date, in Australia, that doesn’t appear to have been the case.”

Professor Palombi was less positive about the prospects for a broader impact in Australia.

“The patent claims in question are to pieces of DNA that exist in the human body and the court has said that material is patentable simply because it’s been extracted from the human body,” he said.

“What that means is that anyone who comes along and reproduces that biological material, no matter how they do it, or anyone who wants to use that material in some other way, even if it’s in a gene therapy, can’t do it without the permission of Myriad Genetics.”

“We know Myriad hasn’t been terribly useful in giving permission. That’s why the case started in the United States in the first place, because over there women are paying over US$4,000 to have their genes tested,” he added.

Professor Palombi said the decision was based on a case from the 1950s between the National Development Research Corporation and the Commissioner of Patents that been evoked repeatedly and has meant anything that has had a human hand on it is patentable subject matter in Australia.

“If you apply black letter law and you apply a very extreme interpretation of a near 60-year-old decision that had nothing to do with biotechnology, that’s what we’ve got,” he said.

In June 2013, the US Supreme Court ruled against gene patents in a similar case that involved the same company. Myriad Genetics owns the patents to the BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations and fought the case through the US court system for years until finally losing it at the Supreme Court.

The Australian case only involved the BRCA1 gene mutation, and the court heard the case over a year ago. In its decision, the bench was critical of the final US decision noting a preference for the decision that was overturned by the Supreme Court.

“It’s unprecedented to have a court of this kind actually do that to the Supreme Court,” said Professor Palombi. “I don’t know of any other decision in the English-speaking world where this has happened.”

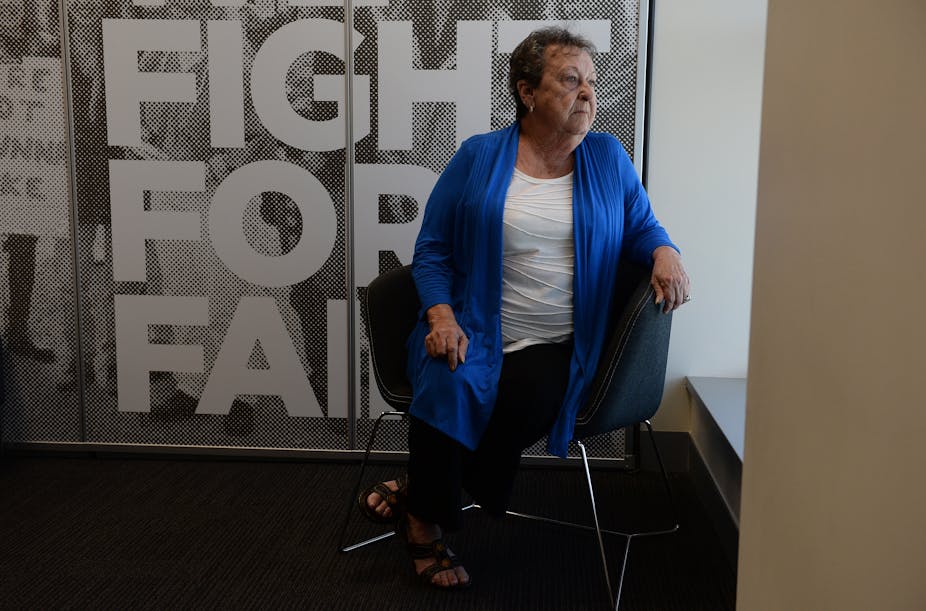

Lawyers at Maurice Blackburn who brought the case on behalf of a cancer survivor Yvonne D'Arcy told Fairfax media “the only way to overturn the decision would be if the firm was granted leave to appeal to the High Court.