The Liberal Party seems to be falling for “Balmain basket weavers” syndrome. This is what Paul Keating called Labor members who put ideological conviction ahead of electoral success. It was a problem that had bedevilled Labor in various forms since it split in the first world war, when Prime Minister Billy Hughes fell out badly with the industrial left over conscription.

Labor split again in the early 1930s over how to deal with the Depression: maintain incomes or pay the bond holders. Both of those crises were resolved by a section of the party’s right joining with the Liberals and forming a new party, but the potential for conflict was baked into an organisational structure that gave party bodies outside of parliament power over the policy directions of the parliamentarians.

Gough Whitlam largely solved the problem after he became Labor leader in 1967 by increasing the power of the parliamentarians to introduce the middle-of-the-road policies that win Australian elections. The Greens have now sheared off much of Labor’s left and, in the NSW parliament, Balmain is represented by the Greens.

Read more: The Turnbull government is all but finished, and the Liberals will now need to work out who they are

For months now, Liberals unhappy with the leadership of Malcolm Turnbull have complained that he was alienating the party base. They claim he is Labor-lite; an opportunist who has used the party to fulfil his lifelong ambition to be Prime Minister, and the leadership conflict is a battle for the heart and soul of the party.

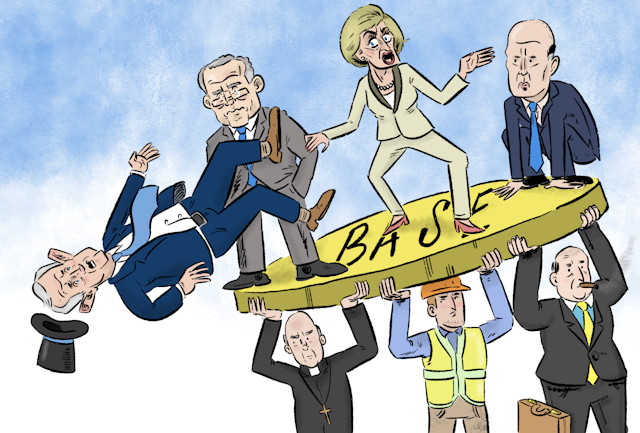

But where is this heart and soul, and how strong is it? Let’s be clear – the continually appealed to “base” is not very many people. At a generous estimate there are about 50,000 party members spread across the 150 electorates. To be sure, their time and money are crucial for electioneering, but they still only have one vote each.

Then there is the conservative vote. The same-sex marriage survey gave us some indication of its size. This was an identity issue, a symptom, opponents said, of the political correctness that is undermining Western civilisation. Conservative Liberals Tony Abbott, Peter Dutton, Scott Morrison and a swag of backbenchers all publicly supported traditional marriage.

But mainstream Australia overwhelmingly voted yes, by 61.6% to 38.4% of the almost 80% of the electorate who voted in this non-compulsory plebiscite. The highest “no” votes were not in the Liberal heartland, but in Labor seats in the western suburbs of Sydney, with high populations of religiously conservative people of Middle Eastern background. The “yes” vote in Tony Abbott’s seat of Warringah was 75%. Surely, this tells Liberal strategists something about the party’s base when a key belief of its conservative wing is so roundly rejected.

Of course, this is just one issue. The conservatives have since shifted their focus to the defence of religious freedom, with the federal parliament more overtly religious than the population at large.

Then there is climate change and the call to dump our modest Paris targets. For the past ten years, climate denialism, sometimes disguised as scepticism, has been an identity marker among ideological conservatives, impervious to all evidence as well as to the laws of physics and chemistry.

Given that most Australians now accept that climate change is happening, conservatives have shifted the goal posts here too, to energy prices and their pressure on cost of living, to give their climate denialism an acceptable face. But there are many cost of living pressures – such as the shift in the balance between wages and profits in the last ten years of stalled wage growth, the casualisation of the workforce, the cost of child care or transport.

Same-sex marriage, religious freedom, climate change denial: these are the preoccupations of the Liberal Party’s equivalent of the Balmain basket weavers. They are putting loyalty to their minority ideological convictions ahead of winning elections, and have torn down a leader for being too mainstream.

This is something new in the Liberal Party, which has always been a pragmatic, leadership party that prided itself on offering steady, competent, non-ideological government. Historically, it has been the beneficiary when ideological warriors split the Labor Party. In both 1917 and 1932, it returned to government in a reformed party behind an ex-Labor leader, and could plausibly claim to represent the national interest.

Now Labor is the beneficiary as ideological warriors split the Liberals, and looks set to become Australia’s natural party of government.