The unexplained death of Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old black man, after his arrest on April 12 has spawned two days of intense riots in Baltimore following his funeral on April 27.

Gray, who was carrying a switchblade, was arrested on suspicion of drug activity on the grounds of the Gilmor Homes social housing development in Baltimore’s notorious Sandtown-Winchester neighbourhood.

A video surfaced of Gray’s arrest that showed him screaming in pain as a police officer pressed his knee against his neck; later in the video several police officers dragged a listless and unresponsive Gray into a police wagon as on-lookers shouted that Gray was clearly in need of medical attention.

What happened in the 45 minutes after his 8.39am arrest has sparked protest. After being loaded into the police wagon, Gray was not fastened into a stationary position with a seat belt. While the Baltimore Police Department has conceded that its officers failed to follow proper procedure, many suspect malicious intent; the city police department is renowned for its use of the intimidation tactic of “rough riding”, or failing to secure suspects in transport in order to cause discomfort and instill fear.

The practice of rough riding can be particularly dangerous and suspects are usually handcuffed, which prevents suspects from bracing themselves from injury. At some point during transit, Gray suffered a medical emergency. Gray’s spine was severed severely from his neck and he sustained three fractured vertebrae. Although Gray was rushed to the University of Maryland Medical Center, he died seven days later on April 19.

While protests began peacefully on April 27, they quickly descended into rioting, and a state of emergency has now been declared in Maryland. By April 28, 235 arrests had been made (including 34 juveniles), 144 vehicles had been burned along with 15 buildings and 20 police officers wounded. More than 400 Maryland state troopers and 1,700 Maryland national guardsmen were deployed to restore order to the city, which is under a strict curfew from 10pm to 5am.

Even the city’s storied baseball club, the Orioles, has been affected by the riots; two games against the Chicago White Sox were postponed. Put simply, Baltimore is under a level of duress that is disconcerting for such a large city.

Yet while the riots are attributed as a reaction to the death of Gray (similar to events in Ferguson), the truth is much more complicated. Indeed, there are many dissimilarities between Baltimore and Ferguson. While Ferguson had little black political representation and a police force that didn’t reflect local demographics, Baltimore has a black mayor and several black city councillors – and while the police force is majority white, nearly 45% of officers are black.

So, if black Baltimoreans have made great strides in achieving political power in the city (in contrast to Ferguson), what then explains such acrimonious rioting? I believe that the historical legacy of the city’s institutionalised racial housing segregation covenants and their impact on slum housing in the city have contributed to the systemic poverty and geographic isolation of the city’s majority black population.

In fact, there is a direct causal relationship between Gray’s death and the environmental condition of Baltimore’s slum housing.

How they built Baltimore’s ghettos

Ever since 1910, when a black lawyer attempted to purchase a home in Baltimore’s affluent Edmonson Village, the city relied on what came to be known as “housing covenants”. These covenants were legal ordinances enacted by the city to prevent black encroachment on white residential neighbourhoods.

Regardless of the level of black population growth, the covenants prevent black neighbourhood expansion – by the 1940s black people constituted more than a third of the city’s population but occupied only a fifth of urban space. While several Supreme Court cases invalidated Baltimore’s housing covenants, the covenants continued to be de facto law into the early 1970s, as Baltimore politicians and real-estate interests colluded to restrict the growth of black neighbourhoods. This process resulted in black Baltimoreans crowding into already sub-standard slum housing districts.

Although white flight eased tensions over neighbourhood expansion that began in the 1960s, the housing that was left was in particularly poor shape. Baltimore has been a majority black city since the mid-1970s, but the legacy of its racial housing policies continue to affect public health in the city to this day. One of the most striking examples of how housing policy has damaged black health is the example of lead paint poisoning.

Lead poisoning

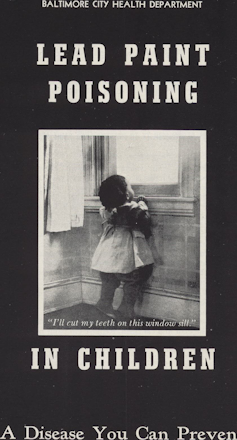

Lead-infused paint was commonly used in Baltimore’s working class row-houses built in the late 19th and early 20th century. Most of Baltimore’s private housing stock derives from this period. After several epidemics of lead-paint poisoning and lead-induced meningitis in Baltimore’s children in the 1920s and 1930s, the Baltimore City Health Department attempted to ban the use of lead-based paint in Baltimore homes.

The BCHD found that lead paint poisoning was particularly acute among children, who were apt to eat sweet-tasting lead paint chips that peeled off the wall. Lead-paint poisoning in children was found to induce neurological problems, and children with lead-paint poisoning suffered in school. Despite the dangers of lead-paint, the lobbying efforts of Felix Wormser and the Lead Industry Association ensured that lead paint remained a staple of Baltimore housing construction and refurbishment.

It was not until Richard Nixon signed the Lead Based Paint Poisoning Prevention Act (LBPPPA) in 1971 was there an effective legal tool to combat the continued use of lead paint. But tens of thousands of Baltimore row-houses remained encrusted with lead paint. Coincidentally, Gray grew up in one such toxic row-house.

Gray spent the first years of his life at 1459 North Carey Street, in the impoverished Druid Heights neighbourhood, less than ten minutes’ walk from the Gilmor Homes projects where he was apprehended. While the Gilmor Homes development suffers its fair share of social problems, Gray would have had a much better chance of surviving his scuffle with the police had he had the benefit of social housing tenancy. Literally.

Gray’s mother Gloria Darden filed a lawsuit in the early 1990s against the landlord of her row-house, Pikesville resident Stanley Rochkind, in protest of his failure to remove lead paint from the home, for which Darded paid US$300 a month. All three of Darden’s children, older daughter Carolina and twins Freddie and Fredericka, tested with abnormally high levels of lead in their blood (technically, any amount of lead in the blood is hazardous).

As a child, Gray had his blood tested six times between 1992 and 1996. On one occasion, he tested as having 19 micrograms per decilitre (mg/dL) of lead in his blood; the state of Maryland permits lead levels lower than 10 mg/dL.

While the trial was set for late 2009, it was postponed by the state to make room for four other lead paint poisoning suits: all direct against Rochkind. The case eventually settled for an undisclosed amount.

Additionally, Gray received treatment as a youth at the Kennedy Krieger Institute, a Baltimore hospital that treats children with illnesses of the brain, spinal cord, and musculoskeletal system. His medical treatment did not prevent the onset of negative health effects, however. In addition to being born two months premature, Gray was diagnosed with ADHD and later dropped out of high school after failing several grades. He started using heroin, had been arrested 24 times before his final arrest and had served time in prison for a drug possession charge.

All-too common

Yet what makes Gray’s story so tragic is not its uniqueness, but rather its commonness.

Tens of thousands of slum houses in Baltimore are encrusted with poisonous lead paint. Furthermore, lead paint is just as pervasive in abandoned houses, and this lead contributes to an environment deleterious to public health.

In the Sandtown-Winchester neighbourhood where Gray was apprehended, 30% of private stock houses are either vacant or abandoned. Some 7% of young children in the neighbourhood have elevated lead levels in their blood. The connection between Gray’s death and lead paint might seem far-fetched if it weren’t so blatant.

While it is possible that Gray might have lived a longer, healthier life if he had lived in Gilmor Homes rather than a lead-laden row-house, the fact remains that Baltimore’s history of institutionalised racial segregation has contributed to the dereliction of the city’s row-housing slum districts.

Given that so many people are compelled to live in these unhealthy homes due to a lack of supply of adequate social housing – it is not surprising that Gray’s death has incited indignation. While riots cannot be condoned, their root causes must be considered if they are to be prevented in the future.

Gray’s death tipped Baltimore into turmoil, but his death is not the cause of the rioting. Rather, the city’s municipal legacy of racial segregation and its failure to provide healthy, affordable housing for its working-class Black population have cultivated feelings of anger and hopelessness in much of the city’s young people.