Twenty years ago, on April 15, 1998, Pol Pot, the leader of Cambodia’s genocidal government during the late 1970s, died in his sleep at the age of 73. Born Saloth Sar, Pol Pot was never held accountable for the crimes committed during the three years, eight months and 20 days his Khmer Rouge government subjected the Cambodian population to a reign of terror. Almost 2 million people, one-fourth of the country’s population, perished during this time from starvation, disease and execution.

In the search for truth and justice, many Cambodian survivors have looked to the U.N.-assisted tribunal currently in progress in the capital city Phnom Penh. Convened in 2006, the tribunal has sentenced the head of the main Khmer Rouge torture center to life in prison.

The tribunal’s second trial is nearing completion and is expected to result in life sentences for two additional high ranking Khmer Rouge leaders as well. At that point, the tribunal will mostly likely close its doors, and the U.N.-appointed judges and lawyers will go home. The tribunal is a classic example of “justice delayed is justice denied.”

For the past 30 years, I have studied the legal, political and literary responses to the Cambodian genocide. It is the literary responses – accounts written by survivors themselves – that show how in breaking their silence and in speaking on behalf of those who died, they were able to seek justice and healing.

The Killing Fields

Two important texts, Haing Ngor’s “A Cambodian Odyssey,” published in 1987, and Vann Nath’s “A Cambodian Prison Portrait,” published 11 years later, reveal the extraordinary events that led to their writing and publication, as well as the authors’ reasons for recording their literary testimony.

Before the Khmer Rouge took power on April 17, 1975, Haing Ngor was a successful gynecologist at a medical clinic in Phnom Penh. During the genocide, Ngor was arrested and severely tortured by the Khmer Rouge on three separate occasions. Each time, Ngor’s wife Huoy nursed him back to health from the brink of death. Ironically, near the end of the genocide, Huoy died in childbirth, because Ngor lacked the simple medical equipment to save her and their first child.

Ngor was able to survive the genocide. He was given refugee status by the American government and resettled in Long Beach, California, which has the largest population of Cambodians in the United States. However, he continued to be racked by guilt over not being able to save Huoy’s life.

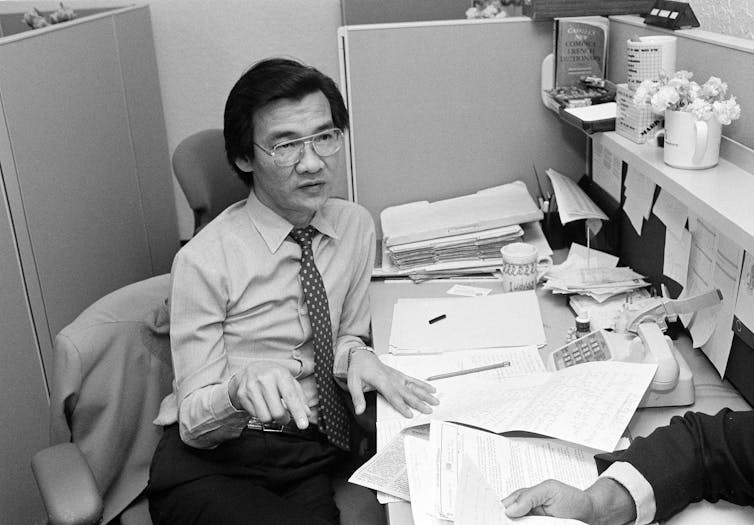

In the early 1980s, the first film about the Cambodian genocide, “The Killing Fields,” was made based on the book by New York Times war correspondent Sydney Schanberg, who reported on the Vietnam War from Phnom Penh. In casting the role of Dith Pran, Schanberg’s Cambodian translator, Ngor was selected out of a crowd at a Cambodian wedding in Los Angeles.

Despite no previous acting experience, Ngor won the 1985 Academy Award for best supporting actor. Ngor’s instant fame from wining the Oscar transformed him from an anonymous survivor into the world’s most prominent witness of the Cambodian genocide.

Two years later, Warner Books published his 500-page literary testimony, “A Cambodian Odyssey,” which describes the conditions of extremity under the Khmer Rouge and specifically chronicles his relationship with Huoy, from the time they met prior to 1975 until her tragic death during the genocide.

Bearing witness to Huoy’s senseless death was essential to Ngor’s process of healing. His newly acquired status as an Oscar-winning actor provided him with the platform to affirm the truth of the Khmer Rouge’s crimes. By identifying the victims and perpetrators of the genocide, he attempted to fulfill his responsibility to Huoy and his family members who died. In the book’s introduction, Ngor states:

“I have been many things in life: a medical doctor … a Hollywood actor. But nothing has shaped my life as much as surviving the Pol Pot regime. I am a survivor of the Cambodian holocaust. That’s who I am.”

Prison Portrait

The second book that I want to highlight is “A Cambodian Prison Portrait,” written by Vann Nath, a painter by trade before the Khmer Rouge takeover in 1975. During the genocide, Nath was arrested and sent to Tuol Sleng prison, where approximately 15,000 people were forced to confess to bogus crimes under torture and subsequently executed. Nath was spared execution at the last moment in order to paint portraits of Pol Pot.

Within a year, the Khmer Rouge regime was removed from power by Vietnamese forces, and Tuol Sleng was transformed into a museum to show the world the atrocities that took place there during the genocide. As one of only seven prisoners known to have survived Tuol Sleng, Nath was asked to paint the scenes of torture and execution he had witnessed to be displayed at the museum.

Deeply traumatized by his year in captivity at Tuol Sleng, Nath later tried to rebuild his shattered life and opened a small coffee shop in downtown Phnom Penh. Two humanitarian workers who frequented the coffee shop befriended Nath and convinced him to tell his story, resulting in the writing and publication of “Prison Portrait,” in 1998.

In 2009, Nath also served as a primary witness at the U.N.-assisted tribunal during the trial of Duch, the Tuol Sleng prison chief, who was eventually sentenced to life in prison. Similar to Ngor, informing the world of the conditions at Tuol Sleng fulfilled a deep responsibility to speak on behalf of those who suffered and died under the Khmer Rouge.

By publishing their personal accounts, as I found in my research, survivors attempt to fulfill a deep responsibility to speak on behalf of those who died. In doing so, they begin to assert some control over the traumatic memories that haunt their lives. These writers act against forgetting in the hope that the world will never allow another Pol Pot to try to silence the voice of the people.

Editor’s note: in a previous version of this article there was an inadvertent typo in the year of Vann Nath serving as a primary witness. It has been corrected to 2009.