The hype over what has been dubbed “deflategate” has obscured some deeper issues about sports history and what is really at stake when teams take to the field for contests of skill and brute force.

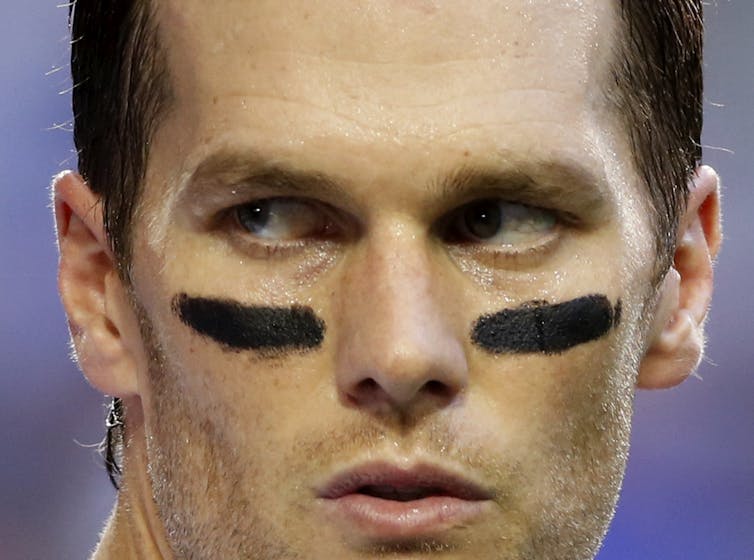

On May 11, the National Football League (NFL) announced disciplinary action against the New England Patriots and star quarterback Tom Brady following a league-sponsored investigation that found that footballs Brady used in a conference game on January 18 had been illegally deflated and that he had known about this. Reaction to the NFL’s actions, pro and con, has been visceral and fierce.

Some perspective is needed: Generally, disciplinary action against professional athletes by the leagues falls into three categories.

Sanctions against players for off-field actions

The first category involves sanctions imposed for actions of players off the field that are unrelated to the games they play. The NFL has experienced a minor epidemic of these recently. Last year, for example, Ray Rice of the Baltimore Ravens received a year-long suspension from the league for hitting his then-fiancée, whom he subsequently married, in an elevator in Atlantic City. Adrian Peterson of the Minnesota Vikings incurred a similar penalty for striking his young son with a tree branch to punish him.

There is something odd about these episodes. Assault is, after all, a crime. The United States has laws, prosecutors, courts and prisons to deal with offenders. A private entertainment company such as the National Football League does not ordinarily function as a parallel legal system.

The accusations against Rice and Peterson were certainly serious, and were in fact investigated by the proper authorities. But for a private company to punish them before the legal procedure in each case had run its course, although permitted by the contract collectively bargained between the NFL and the Player’s Union, has a whiff of vigilante justice.

The effect of mega millions on ‘fair’ play

The reason for what the NFL did to Rice and Peterson – which is the reason for much of what happens in professional sports and indeed in supposedly non-professional collegiate athletics and, for that matter, in much of life – is money.

Professional football is a multibillion-dollar enterprise whose immense profitability depends on the good will of the tens of millions of people who fill the palatial stadiums in which its games are played, buy its merchandise and, most important of all, watch the sport on television. The league’s owners fear that if it becomes associated with criminal conduct, it will alienate its customers. Owners are therefore at pains to be seen as vigorously opposing any kind of criminal misconduct. The sanctions for off-field misconduct are, in the end, exercises in image protection and brand management.

Misbehaving on the field

The other two categories of discipline involve misbehavior on the field. The first and more serious of them is cheating to lose.

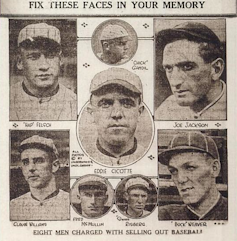

In the most celebrated of all sports scandals, players for the Chicago White Sox – thereafter known as the Black Sox – took money from gamblers to lose the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. Losing deliberately strikes at the heart of any sport, all of which are contests in which the outcome is not known in advance and both contestants – teams or individuals – strive to win. If one side is instead trying to lose – if both ostensibly opposing contestants are actually seeking the same result – what they are staging is not a game at all. It is a scripted drama, like a play, a movie or professional wrestling.

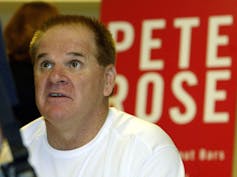

Gambling offers the biggest temptation to cheat to lose. Pete Rose, one of baseball’s greatest players, was, like the Black Sox players, banned from his sport for life for doing so. In the 1960s, two prominent professional football players, Paul Hornung and Alex Karras, were each suspended for a year for gambling.

When a drive to win turns into cheating

The third category of sanctions involves cheating to win, which is what the NFL accuses Tom Brady of having done. Sports are contests conducted according to rules, and breaking those rules incurs penalties. While cheating to lose is the equivalent of a crime against sports, cheating to win qualifies merely as a misdemeanor. It violates not the essence of the game, as the Black Sox did, but rather the spirit of fair play in which the games are expected to be conducted.

Because individual athletes and teams ordinarily do whatever they can to achieve victory – which is almost always more financially rewarding than defeat – violations of this kind are common in sports. The widespread use of performance-enhancing drugs by baseball players in the 1990s is perhaps the best-known recent example.

Here, however, the line between clever gamesmanship and outright rule-breaking is a blurry one, something that the Brady case illustrates. While the rules say that footballs must be inflated to at least a minimum pressure, and Brady and the Patriots are accused of deflating the footballs he used to a point below the minimum, it is permitted – or at least not forbidden – to doctor the balls in a variety of other ways, and teams are known to do so. Some of what they do – making the footballs easier to grip, for example – would seem to help quarterbacks more than lowering the ball’s air pressure could. (Baseball has a long history of pitchers doctoring the balls.)

The life span of a scandal: Tom Brady in September

The Brady scandal has gripped the sports world but is likely to have little long-lasting impact. When the season begins again in September, attention will turn to what really interests the sports-following public: the games themselves. Tom Brady will appeal his suspension and, based on recent precedents and the Patriots’ strong rebuttal to the charges against him and them, he stands a good chance of having it reduced if not eliminated entirely.

The episode may tarnish his reputation and cause him to lose some lucrative product endorsements; but over the last 13 years, through multimillion-dollar annual salaries and a raft of such endorsements, he has probably made more money than Bill Clinton has from speaking fees.

As for football itself, it does face a major threat to its future, but not from any of the three kinds of infractions that are part of sports history. The challenge comes from the accumulating evidence that playing the game leads to serious brain damage. The danger to the sport stems from what it does to the young men who play it, not from what they do to the footballs they use when they play.