While Europe wrestles with the fallout from Britain’s vote to leave the EU, the rest of the world is going about its business. Here, our experts offer their updates.

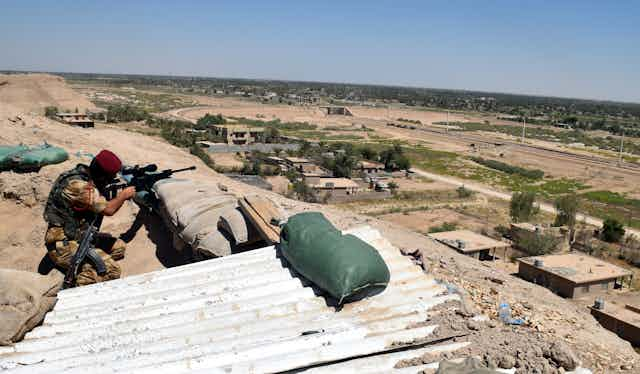

Islamic State lost control of Fallujah

Natasha Ezrow, University of Essex

On June 26, Iraqi prime minister, Haider al-Abadi, proclaimed that the Iraqi military had taken control of Fallujah.

Taking Fallujah is significant for several reasons. Fallujah is better known as the site of the costliest battle of the Iraq War for the US, and has been seen as a symbol of resistance. Less than 50 miles from Baghdad, it has served as the command centre for IS and the staging ground for recent attacks on the capital. This win could hopefully pave the way for the military to stage an offensive in Mosul, the last major Iraqi city IS controls.

This marks a major watershed in the battle against IS. While the group has directed and inspired several terror attacks to keep itself in the headlines, less has been written about its waning power.

The group’s ability to control territory in Iraq is increasingly being challenged by the Iraqi military – and in fact, IS has lost 40% of the populated territory that it once controlled in Iraq. In the past year, key cities of the Anbar province were recently lost to the Iraqi military including its provincial capital, Ramadi.

Though the group still retains some control over parts of Syria, the heart of its power was always in Iraq. Losing Fallujah is another indicator that its grip there is tenuous.

Spain held another election

Karl McLaughlin, Manchester Metropolitan University

The June 26 general election was meant to finally give Spain some closure after the inconclusive result at the December poll, which failed to yield a government. In the end, it answered several key questions, but not the main one: who exactly will run the country for the next four years?

As it did in December 20, the People’s Party (PP) won the most seats but fell short of a majority. That said, its increased vote in a low turnout may have strengthened caretaker premier Mariano Rajoy’s hand ahead of coalition negotiations with possible allies.

The election also clarified several other issues. The two new kids on the block, the left-wing Podemos and the centre-right Ciudadanos, had both assumed that impeding the formation of a government under either of the two big parties in December would strengthen their respective hands in a re-run. But events have proven otherwise and the dominance of the two establishment parties, whose demise the insurgents have repeatedly predicted, is now enshrined for the time being.

In the end, when the chips were down – and after the seismic impact of the Brexit result they were – voters opted for the devils they knew.

It’s not as creative an outcome as many had expected, but that’s not to say the election didn’t fire the imagination. One newspaper devised a charming trick to flout Spain’s ban on pre-election polling coverage by reporting on “Fluctuations in the Price of Fruit”, with each party designated as a particular fruit according to its traditional colours. Perhaps this sort of creative reporting could become a new Spanish export.

Read more on the Spanish election result here.

Venezuela sank deeper into crisis

Marco Aponte-Moreno, UCL

Faced with unprecedented economic crisis, hyperinflation, increasing shortages, and violent crime, Venezuelans have just completed the first stage in the campaign to remove unpopular president, Nicolás Maduro, through a recall referendum. They have managed to validate 400,000 signatures in favour of the recall, twice as many as required under the Venezuelan constitution.

The opposition now hopes the second stage, which involves collecting almost 4m signatures, will take place in July. That would allow for a referendum in October or November this year. But the government, which controls the electoral body and all other state powers except for the National Assembly, has other ideas.

According to the constitution, if the president is revoked by a recall referendum before his last two years in office, then a presidential election needs to be held. If it takes place after that deadline, which in Maduro’s case would be after January 10, 2017, the vice-president assumes power. That would allow Maduro’s Chavistas to remain in power until 2019.

In another twist, the Organisation of American States (OAS) has voted to start discussing the Venezuelan case. The purpose of the discussions is to see whether or not to apply the inter-American Democratic Charter, which would exclude Venezuela from the organisation if its member states find that democracy there has ended.

For his part, Venezuela’s besieged president has said that there will not be a referendum this year. He dismissed the OAS efforts to invoke the democratic charter, but has declared that he is willing to start a dialogue through the Union of South American Nations – a regional body currently presided over by Nicolás Maduro.

Read more about the crisis in Venezuela here.

The Pope sent a strong signal on homosexuality

Luke Cahill, University of Bath

During an in-flight press conference returning to Rome from a visit to Armenia, Pope Francis was asked about the comments made by Cardinal Marx. Francis went on to repeat his famous line on homosexuality from 2013: “Who am I to judge?”?

This new way of presenting unchanged Catholic teaching has been percolating in the among some Catholic leaders for a while. After Ireland passed marriage equality last year, the archbishop of Munich, Cardinal Reinhard Marx, spoke of the need not to marginalise gay people.

Marx is a member of the Council of Cardinals, which advises the pope on how to reform the central administration of the Church, the Roman Curia. Marx joined a handful of other prelates and stopped short of praising gay marriage, but indicated the state should make some accommodations for gays in long-term relationships, such as civil unions.

Crucially, at the press conference, the pope twice cited the Catechism of the Catholic Church as the authority for his stance, even though it takes a hard line on sexual orientation:

This inclination, which is objectively disordered, constitutes for most of them a trial. They must be accepted with respect, compassion, and sensitivity. Every sign of unjust discrimination in their regard should be avoided.

While it was good that Francis affirmed what Marx said, the current indications are that the Church will not change its teachings on his watch – and his welcoming tone stops short of real reform, at least for now.

Colombia sealed a ceasefire with the FARC

Sanne Weber, Coventry University

The historic bilateral ceasefire agreement signed by the Colombian government and the FARC means an end to one of world’s longest internal armed conflicts and to one of the oldest guerrilla movements. Yet some procedural steps still have to be taken – and there are also some larger challenges ahead to make peace a reality.

For one, both parties are yet to actually sign the final agreement. The signing has already been delayed by several months, and the Santos government is now hesitant to make promises about the concrete date when the deal will take effect, since the deadlines it’s previously set and then let slip have done its support no good.

Once the deal is formally signed, the FARC will disarm within 180 days, monitored by a special UN mission. There will be a plebiscite for the population’s approval of the peace agreement. After long discussions, both parties have agreed for the Constitutional Court to decide on the precise mechanism.

There are other, more general challenges ahead in the process of the FARC’s reintegration into civilian life. Many Colombians have shown scepticism towards the idea of the FARC’s political participation. The FARC itself is also concerned, since a previous attempt to form a political party (la Unión Patriótica) had dramatic consequences, as many politicians were either murdered or exiled, leading to the movement’s annihilation.

This fear might yet be borne out. Other paramilitary groups seriously threaten the fragile peace in different parts of the country. And even though this issue is acknowledged in the ceasefire agreement, combating these criminal groups will prove a real challenge.

And finally, although Colombia’s other major guerrilla group, the ELN, has now also started peace negotiations, as yet it has not been willing to renounce its lucrative practice of kidnapping. The government is therefore refusing to begin the public phase of these negotiations.

Clearly, Colombia has plenty of unfinished business to deal with before true peace can be achieved at last.

Violence intensified ahead of South Africa’s local elections

Alexander Beresford, University of Leeds

Bitter factionalism within South Africa’s ruling party exploded in violence and unrest that has left five people dead and destroyed local infrastructure in the nation’s capital, Tshwane (formerly Pretoria).

The country is gearing up for local elections in August this year. It is widely expected that the dominant ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC), could lose control over some major cities, including Tshwane and Nelson Mandela Bay.

This latest violence, however, has resulted from turmoil within the ruling party itself. It began after Thoko Didiza was named as the party’s mayoral candidate for Tshwane. This sparked protests by those calling for alternative local leaders to represent the party in the elections, and the violence began with the shooting of an ANC member immediately before the announcement was due to be made. The subsequent protests have seen widespread vandalism and looting.

The internal party rifts behind the violence are part of a pattern repeated across the country. In many cases, local ANC factions will struggle to ensure their candidate takes office in the hope that they will subsequently benefit from jobs, services, infrastructure, leadership roles and so on handed out as patronage. The stakes of these contests are high – hence the violence.

Looking ahead, the problem for the ANC is that such internecine factionalism undermines its internal organisation as well as its capacity to govern effectively. Small wonder that South Africa’s largest opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, believes that recent events will bolster its campaign to unseat the ANC. And so to the elections in August.

Read more about the violence in South Africa here.