South Africans had specific attitudes to American jazz during the liberation struggle against apartheid. The late trumpeter Johnny Mekoa told me in an interview for my book, “Soweto Blues: jazz politics and popular music in South Africa”:

People were listening to this music at home because we felt this was our music and these are our black heroes.

For South Africans aspiring to freedom, jazz was protest music. In struggle, jazz offered shared, collective messages of black intellectual attainment – and beauty.

It’s therefore not surprising that jazz plays a starring role in Mandla Dube’s 2017 biopic “Kalushi” – the story of South African freedom fighter Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu. Today, few of those born later know Mahlangu’s story. But in telling it, the film takes too little care over factual accuracy, and narrows and distorts what jazz meant to those fighting on the front lines for liberation.

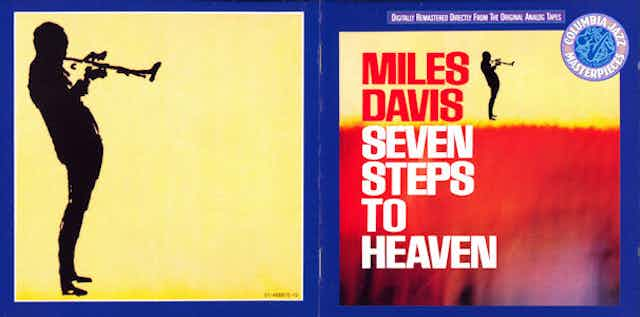

In the opening minutes of biopic we see the young Kalushi parting with his savings for a copy of the Miles Davis LP Seven Steps to Heaven in a general store in the Pretoria township of Mamelodi.

The scene was inspired by Kalushi’s well known fondness for Davis. But according to score composer Rashid Lanie,

When I first saw the first scenes of Solly carrying Miles Davis’s ‘Kind of Blue’ album… I said: ‘I don’t think we should use that visual – let’s change it.’ When Solly walks to the gallows, it is 52 steps to the gallows. Five plus two is seven. Did you know Miles Davis also has an album called ‘Seven Steps to Heaven?’

That’s why, in the film, Kalushi is seen carrying the ‘Seven Steps to Heaven’ LP.

Military training

That’s not the last time Davis appears. The album is used by Kalushi’s struggle contact (a thuggish character first shown stabbing someone in a back alley) to pressure him into political activity. It survives jumping the border, and military training in a camp of the African National Congress (ANC) army in exile, Umkhonto we Sizwe. Kalushi’s final words as he heads for the gallows have become immortal:

Tell my people that I love them and that they must continue the struggle.

In the film, they are reduced to a coda after Kalushi muses:

You know, Miles Davis once said: ‘If somebody told me I only had one hour to live, I’d spend it choking a white man. I’d do it nice and slow…’

Which is all very well, except that if those words of Davis’s were spoken at all, they were uttered six or seven years after Kalushi’s judicial murder at the gallows by the South African state.

Davis has often been invoked to signify the kind of outspoken black pride that scared the white jazz establishment. But while the trumpeter had his ugly side – especially in terms of how he bullied women – his comments on race were incisive and intelligent: firmly grounded in experience.

South African music professor Salim Washington comments in a recent email interview I did with him:

Miles flouted the absurd rules while inventing a cooler and more inventive way to be, in a world designed to make black men politically impotent and culturally neutered … But sometimes it seems he is cited as a bad boy and not as a thinker, which he was.

See, for example, the 1962 Playboy interview with Alex Haley.

Questionable provenance

The “choking” comment, however, has a questionable provenance. It is cited by the American Jet magazine on 25 March 1985 (Mahlangu was executed on 24 July 1978) as coming from a “recent” interview with USA Today reporter Miles White. Jet completes the quote as:

The only white people I don’t like are the prejudiced white people. Those the shoe don’t fit, well, they don’t wear it.

Before Kalushi, it was widely republished on ultra-right white supremacist websites.

Framing Davis this way reinforces other conservative tropes in the movie; tropes already prevalent in hegemonic discourses about revolution. Anti-apartheid youth rebellion in Mamelodi appears as a few isolated young individuals (one, a murderous thug) restrained by their frightened families, echoing multiple Hollywood biopics where the revolutionary is an anomic individual amid apolitical peasants muttering,

All we want to do is herd our goats in peace.

What’s missing from the film

Wholly absent from the film is that Mamelodi had for two decades before 1976 been a multi-generational ferment of ANC, Africanist and black consciousness community revolt and cultural activism, led by the kinds of older heroes from whom Kalushi would have learned about both politics and Miles, such as the late cultural activist Geoff Mphakati.

On top of this the film images Africa – Mozambique and Angola – in “basket-case” terms. The first thing Kalushi sees arriving over the border is a helpless young orphan begging in Xai Xai refugee camp, followed by unexplained executions: his first sight as he arrives at the MK training camp in Angola. Umkhonto we Sizwe political education is portrayed as mindless sloganeering, when ANC stalwart Jack Simons’s political lectures and diaries (of which I was co-editor) make it very clear the process had significantly more content and nuance.

By the end, Kalushi’s final words – addressed to “my people”: his community, placing love at the roots of struggle – have been negatively re-contextualised by Davis’s supposed individualistic vengefulness. Kalushi faithfully carts his LP around the perilous frontline (something unlikely to the point of fairytale) but “choking a white man” is the only rationale for why.

“Don’t worry about playing a lot of notes,” Davis legendarily said. “Just find one pretty one.” The late trumpeter and Umkhonto we Sizwe combatant Dennis Mpale spoke to me of jazz,

[making] beautiful music in a very ugly world.

South Africa’s freedom fighters yearned for chances to listen.

Sticking out of the charnel-house debris created by the South African Defence Force when they murdered artist Thami Mnyele in Botswana in June 1985 was the cover of the John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman jazz album. The story of jazz, in Umkhonto we Sizwe culture and Kalushi’s life, is far more nuanced – and positive – than a poorly sourced quote from Jet magazine.