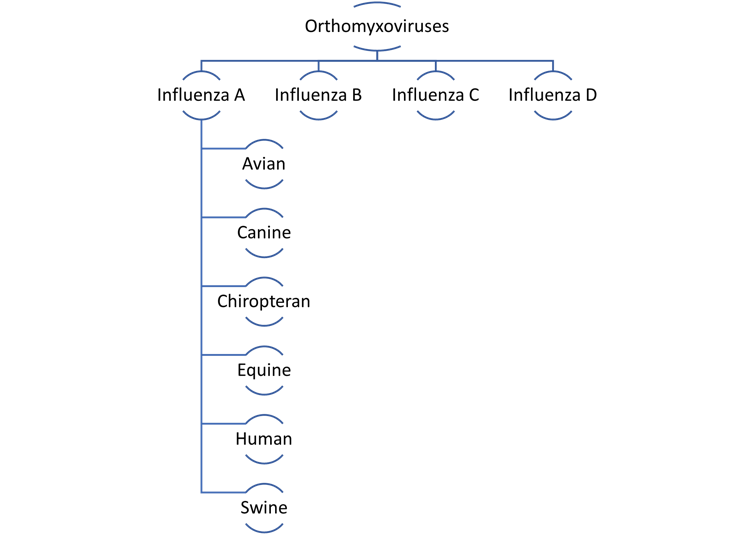

Avian influenza (“bird flu”) is a highly contagious viral infection that affects wild and domestic birds worldwide. It has recently gained notoriety for its devastating impact on the commercial poultry sector and as an emerging human public health threat.

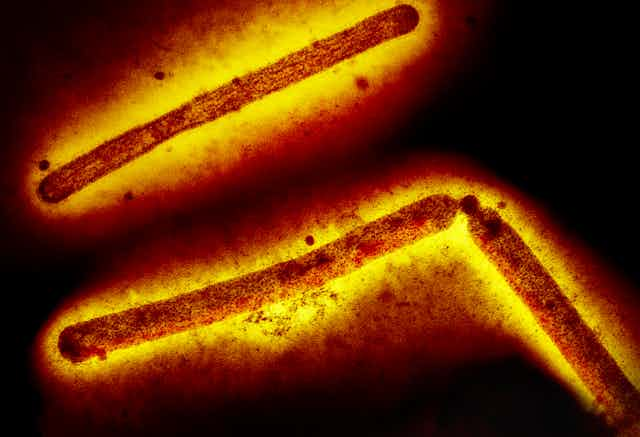

What are avian influenza viruses?

Influenza viruses belong to the Orthomyxovirus family and are grouped into four species designated by the letters A (Alpha), B (Beta), C (Gamma) and D (Delta). Almost all influenza infections in humans are caused by influenza A and B viruses.

Influenza A viruses have been named avian (bird), swine (pig), equine (horse), canine (dog), chiropteran (bat) and human, based on their natural reservoir (the organism where they are most commonly found).

Avian influenza and other Influenza A viruses are categorized into subtypes according to the composition of their hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) surface proteins. There are 18 known H types (H1 to H18) and 11 known N types (N1 to N11). The combination of an H type and an N type defines a specific influenza virus subtype (for example, H5N1).

What do we know about avian influenza?

Avian influenza (“bird flu”) was first described in the late 1800s. It’s a highly transmissible and usually mild disease of wild birds such as geese, swans, seagulls, shorebirds, and also domestic birds such as chickens and turkeys. It is usually caused by influenza A viruses with an H5 or H7 hemaglutinin type, for example, H5N1 or H7N9.

While many forms of these viruses are minimally virulent — meaning they cause mild disease — some are highly virulent, meaning that they cause more serious disease. Millions of poultry deaths in Asia, Europe, the Americas and Australia have been attributed to highly virulent forms of H5N1, H5N8, H7N7 and H7N9, with H5N1 accounting for the vast majority of cases.

In Canada and the U.S., outbreaks of H5N1 influenza in domestic and wild birds have been reported in most regions.

How is avian influenza transmitted to humans?

Avian influenza viruses are not easily transmitted from birds to humans or to other animals. Humans are accidental hosts — meaning that the virus does not typically circulate among people. Humans may acquire the virus after inhaling birds’ respiratory droplets or exposure of their mucus membranes to bird feces, saliva or contaminated surfaces.

Bird flu cannot be transmitted by eating cooked poultry products. Always follow food safety guidelines for cooking and for handling raw poultry.

Recently discovered mutations in the neuraminidase (N) gene of H5N1 viruses isolated from humans appear to promote bird-to-human transmission. Fortunately, human-to-human transmission is extremely rare.

When was avian influenza first reported in humans?

The first human cases of avian influenza were reported in 1997 by public health authorities in Hong Kong. These infections were linked to poultry infected with a highly virulent H5N1 subtype. Of the 18 affected individuals, six (33 per cent) succumbed to their illness.

Since then, avian influenza has been responsible for at least 2,600 infections and over 1,000 deaths in humans worldwide. In the majority of human cases, infection was acquired following exposure to live poultry rather than wild birds.

Human infections due to avian influenza viruses have primarily been caused by subtypes H5N1, H5N6, H7N7 and H7N9. All but two of the documented human fatalities to date have occurred in low-to-middle-income countries, likely as a consequence of the total case burden and lack of access to antiviral drugs.

What are the signs and symptoms of avian influenza in humans? How is it diagnosed?

Early symptoms of avian influenza in humans are similar to those caused by seasonal influenza viruses such as H3N2 and H1N1. Typical symptoms include fevers, chills, muscle aches, cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, headache and fatigue.

Infections caused by highly virulent forms of H5N1 or H7N9 subtypes may follow a more severe course of illness characterized by internal bleeding, multi-organ failure and a high mortality rate.

The combination of an influenza-like illness and a recent history of exposure to live poultry should raise suspicion for avian influenza. The diagnosis is confirmed by detection of viral RNA in nasopharyngeal specimens using tests for specific subtypes.

What treatments are available for avian influenza?

Antiviral drugs belonging to the neuraminidase inhibitor (such as oseltamivir) and endonuclease inhibitor classes (for example, baloxivir) appear to be highly effective against most avian influenza subtypes, including H5N1 and H7N9. However, antiviral resistance has been well documented and represents a threat to the potency of these agents in the face of constant viral evolution.

Is there a human vaccine against avian influenza?

Licensed vaccines exist to protect humans against avian influenza, although they are not commercially available.

In 2007, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved an H5N1 vaccine for adults ages 18 and older. These vaccines form part of the U.S. government’s Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) of medicines for deployment in the event of a public health emergency. In 2013, the FDA approved a second H5N1 vaccine that is also part of the SNS.

Similar vaccines are licensed in other jurisdictions. All of these vaccines were shown to be safe and effective at the time of approval.

In contrast, H5N1 vaccines for use in animals are commercially available. Vaccination of poultry has been widely adopted in China and other low-to-middle income countries. The U.S. and Europe are gearing up for a massive poultry vaccination campaign to curtail the spread of bird flu.

How else can I protect myself against avian influenza?

Avoiding direct contact with live poultry is perhaps the single most effective measure to prevent development of avian influenza. If exposure to potentially infected birds cannot be avoided, personal protective gear including gloves, gowns, face masks and eye shields should be worn. Hands should be thoroughly washed with soap and water after all potential exposures. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers are less effective at inactivating influenza viruses compared to handwashing.

Are bird feeders safe to use?

Although there is currently a negligible risk of developing avian influenza following wild bird exposure, there are divergent opinions on the role of bird feeders in potentially spreading the disease.

The British Columbia Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals recommends temporarily abandoning the practice of using backyard bird feeders. In contrast, the U.S. Department of Agriculture does not recommend against their use unless poultry are being farmed in the area.

Is avian influenza the next viral pandemic?

There is no way to predict if avian influenza will evolve into a pandemic affecting humans. Mitigation strategies to prevent cross-species transmission include large-scale pre-emptive vaccination of domestic birds and culling of infected flocks.

Of major concern is the potential for novel avian influenza subtypes to emerge through antigenic shift. This phenomenon involves reassortment of hemaglutinin and neuraminidase genes when a single host is infected with more than one viral subtype. As such, avian influenza is a prime contender as a pandemic viral disease of animals and humans alike.

Current stockpiles of avian influenza vaccines for human use will likely be inadequate to meet societal needs should there be a surge in human infections over time.