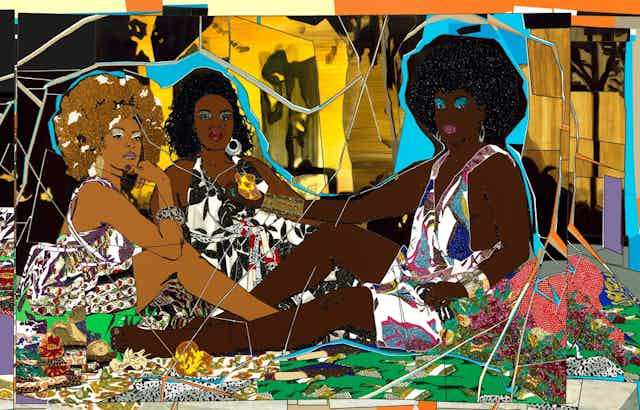

Renowned visual artist Mickalene Thomas has taken over the fifth-floor gallery space of the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) with her show “Femmes Noires.” Working with curator Julie Crooks, it is the first time the Brooklyn-based artist has staged an exhibition in Canada — and it is only the second time the AGO has exhibited the work of a Black woman artist.

Thomas’s exhibit is a powerful and extraordinary contemplation on the intersections of being both Black and a woman. Thomas takes inspiration from multiple art forms, movements and histories, like Impressionism, and focuses on issues such as race, representation, sexuality and Black celebrity culture.

As a Black woman, it is the first time I have ever walked the floors of the AGO and have seen myself reflected back at me. However, something for Canadians like myself to note is that Thomas’s visioning of Black womanhood is from an American point of view.

(The last solo exhibition by a Black woman at the AGO took place in 2010 — “This You Call Civilization?” featuring the work of Kenyan-born, New York-based Wangechi Mutu.)

Blackness in Canada has often been framed through an African-American lens. This representation (or lack of) is an issue I fully explore in my book, Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada’s Black Beauty Culture.

For example, one of the reasons why Black beauty culture has not received much attention in Canada until now is because the task of locating Black voices in the Canadian historical record has been and remains a difficult challenge. Across the border, there are archival collections dedicated to African Americans, such as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, but we don’t have anything like this in Canada.

Media circulates African American experiences

When I started researching Black beauty in Canada, most people were shocked there was enough material for me to write about in a book. The assumption was that the topic would have to focus squarely on African-American women.

For decades, Canadian cultural institutions have consumed African-American desires and fantasies as stand-ins for Black Canada. As a result, Black Canadian representations in popular culture have been rendered invisible.

Throughout the 20th century, cultural and economic practices were co-produced through the circulation of “African-Americanness” through media. From African-American TV shows in the 1970s, films in the 1980s and beyond, Canadians probably know more about the African-American experience than they do about Black Canadians because of media culture.

Canada’s media culture has participated in the creation of identities that privileged African-American images, products and ideologies. These identities originally crossed the U.S./Canada border as desires and fantasies represented in advertising and, later, television and film, and today, art.

Black Canadian women are here

When Trey Anthony’s ’da Kink in My Hair TV series appeared from 2007-09 (based on the play of the same name), it was the first comedy series created by and starring Black women on Canadian national television. The broadcast of ’da Kink in My Hair happened nearly 40 years after Julia (1968–71) in which Diahann Carroll became the first African American woman to star on a U.S. sitcom in a non-stereotypical role. The representation gap between African American women and Black women in Canada spans decades.

To make up for some of this historical invisibility, this month and throughout the winter, the AGO’s “In the Living Room” series will feature Black Canadian women engaging with Thomas’s art and discussing their experiences.

Each talk will be set in the Femme Noires’ living room space, which is modelled after Thomas’s childhood home growing up in New Jersey. The patchwork chairs and books from African-American women authors become the art installation. Visitors are called to engage intimately with the paintings, installations and videos on the walls but also the productive space, the living room, that birthed Thomas’s art in the first place.

The first discussion in the series, “The Dis/Appearing Black Body,” will feature portrait photographer Jorian Charlton and Shantel Miller, an artist-in-resident at Nia Centre for the Arts in Toronto, to discuss Black bodies, power and the gaze.

Black beauty is always political

While I can say much about the differences between Black Canadian experiences and African-American ones, there are universal Black beauty experiences that unite all women of African descent. For example, one of these experiences is the caring for and discussions around Black hair. Some of these public conversations are hurtful to many Black women.

The New York-based online platform, Hello Beautiful, which targets their articles toward Black women, recently asked why Black women should have to defend wigs and weaves more than other women. The article explores why Black women are constantly asked to defend being women and all the things we do, like our hair, to feel beautiful.

On the one hand, our hair is connected to many painful childhood memories of being teased by other children (and sometimes adults) about our various braided hairstyles. On the other hand, natural hairstyles like Afros, dreadlocks or cornrows (tightly braided rows of hair) might denote a Black woman’s politics, but they can also be just a hairstyle or her preference, with no political meaning whatsoever.

Black women who wear hair weaves or wigs can also be the subject of ridicule. In 2017, former Fox News host Bill O’Reilly was forced to apologize to California Congresswoman Maxine Waters, who is African American, when he made disparaging comments about her hair on the cable news program, Fox and Friends. He described her straightened hair as a “James Brown wig.”

Black hair is constantly debated, politicized and misrepresented in media, art and popular culture. A simple decision about wearing it natural or straightened could result in punitive action — not in America, but right here in Canada. This was the case for a waitress-in-training who lost her job at Jack Astor’s because she wore her hair in a bun, and not “down” as required by female wait staff while working at the restaurant.

Black hair stories resonate with Black Canadian women, too. But resonance is not the same as representation.

Why have Black Canadian women artists not been given the same opportunity to exhibit their work as solo artists in Canada? This question about Black Canadian artists and how Black art has been represented and circulated has become prominent in Canadian media lately.

In an article for Canadian Art, Connor Garel wondered why no Black Canadian woman has ever had a major solo exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO).

Curator Ashley McKenzie-Barnes wrote an article for the Toronto Star, and argued that Canadian art fairs, public art installations, festivals, major institutions and galleries need to make space for Black Canadian artists. She is right. We’re doing the work — now we need the space to get recognized for it.