All national cinemas outside of Hollywood have to strive hard to maintain their local industries – and Australia is no exception. So Umbrella Entertainment is to be commended for re-releasing on DVD over the next two years seven classic films from legendary Australian filmmaker Charles Chauvel, with help from Chauvel’s grandson, Ric Chauvel Carlsson, and the National Film and Sound Archive (NFSA).

Chauvel was a major director, producer and writer of early Australian cinema and his films are among the few made before the 1970s that are still regarded as classics. Two of his most significant works – Forty Thousand Horsemen (1940) and The Rats of Tobruk (1944) – are first in line for re-release. They will be followed by Heritage (1935), Uncivilised (1936), In the Wake of the Bounty (1933), Sons of Matthew (1949) and possibly his most iconic film, Jedda (1955).

The re-release of Forty Thousand Horsemen and The Rats of Tobruk is nicely timed given 2015 will mark the centenary of the Anzac landing at Gallipoli. Produced during the second world war, these two films aimed to inspire the war effort and bolster the Anzac legend.

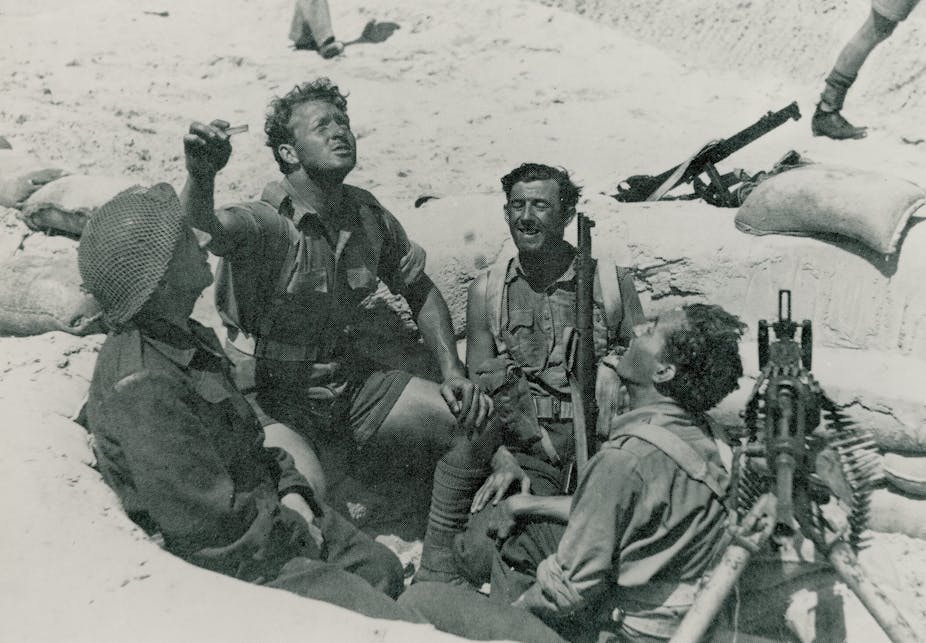

Forty Thousand Horsemen tells the tale of the Anzacs – and broke all box office records when it was released. It was even screened in Europe and Asia. The Rats of Tobruk also celebrated the endeavour and bravery of Australian troops, but five years into the second world war, the devastation and sorrow felt by the nation also makes its mark in the film.

Our forgotten film history

Charles Chauvel worked with his wife Elsa, who co-produced and co-wrote the majority of these films. They were one of the many husband and wife collaborators in the history of Australia’s silver screen. Others include Louise Lovely who worked with Wilton Wench (For the Term of His Natural Life, 1908), and Lottie Lyell, who worked alongside Raymond Longford to make such films as The Sentimental Bloke, (1919).

In Australia, we don’t tend to remember our cinema heroes, especially those who worked before the film revival of the 1970s. Even film buffs are more likely to recall the names of international greats such as Alfred Hitchcock and John Ford than names like Longford and Chauvel.

The struggle to maintain and develop Australia’s rich film heritage goes on, although the current government does not appear to value this endeavour. It was announced earlier this month that the National Film and Archive (NFSA) would lose 10% of its staff. That’s why the move by the NFSA to link with a commercial entity is important in making Chauvel’s significant works available for viewing.

Coming soon to a small screen near you

So what is Chauvel’s legacy? He had a strong directorial voice and a fiercely nationalistic vision, and according to film historians Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper, he wanted to tell stories that “could only be told in Australia by Australians”.

Chauvel’s films took audiences into places filmmakers, even today, hesitate to go. Jedda, for instance, offers spectacular vistas of the Northern Territory, being shot in difficult locations including the landmark sights of Standley Chasm, Ormiston Gorge and the buffalo and crocodile infested Mary River area in Australia’s far north.

Jedda was a groundbreaking film on three distinct fronts. It was the first Australian film to star Indigenous Australians; the first to be invited to the Cannes Film Festival in France; and the first to be made in colour. Indeed, the Chauvels had to store the sensitive colour film stock in rivers and caves during the shoot.

The Chauvels were important in launching the careers of numerous Australian actors. Most notable was Errol Flynn, whose screen debut was in the Chauvels’ first talkie: In The Wake of the Bounty (1933).

Others include Chips Rafferty, the star of Forty Thousand Horsemen and The Rats of Tobruk. Rafferty was regarded as the iconic Australian of the period, much as Paul Hogan or Russell Crowe have worn the mantle in contemporary times. The Chauvels also launched the career of Michael Pate in his first screen role in Sons of Matthew, who went on to star in film and television roles in Australia and overseas.

When will you see your next Australian classic?

At the 2013 AACTA Awards, Russell Crowe asked Australians to “pause next time they’re at the cinema and think about watching an Australian film”.

Crowe is an international star but also a long-term supporter of Australia’s local industry. And his point is well made, given that last year Australian films only accounted for 3.5% of the national box office takings.

If you say you’re a supporter of a vibrant Australian cultural life, when was the last time you stepped out to see an Australian film? How long was it since you saw a classic of our national cinema? And where could you see an Australian classic if you wanted to?

The Chauvel Collection is an opportunity to view those films that scholar Bill Routt has described as those where “intense emotion fuels moral stories about national identity, history, gender and race”.

So when will you see your next Australian film classic?