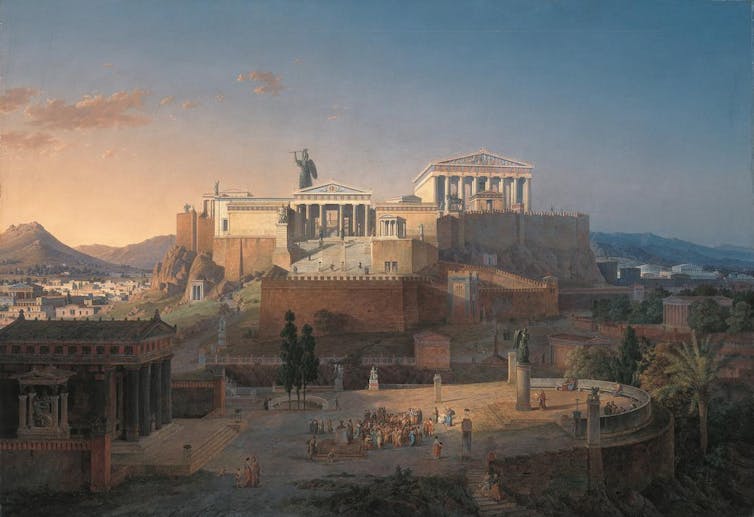

The Parthenon is one of the most famous and recognisable buildings in the world. Designed as a testimony to Athenian greatness, visible miles from the Acropolis (the citadel) on which it stands, the Parthenon still stands proudly among the remains of a massive complex of buildings that celebrated Athens’s deities. It is a witness to the lasting legacy of the ancient Greeks and their architectural ingenuity. But it is also a very good reminder of the fragility of Western power.

It has been seen as central to the history of Western civilisation, a symbol of democracy, and was included on a draft curriculum put forward by the Ramsay Centre, where it is the only work included that doesn’t stem from the Judaeo-Christian tradition.

But the building has a troubled past that is somewhat at odds with our ideas of democratic values.

A potted history

The Parthenon is a temple named for the virgin goddess Athena. It was built from 447 to 432 BCE from compulsory donations by the city’s tributary states. Athens had called on some 200 city-states to support it against the threatening Persian Empire, an alliance known as the Delian League. This ultimately led to the development of an Athenian empire. What started as a united front against an external enemy became an excuse for Athens to gain more ships and then more money from her allies. The Parthenon was built from the profits of this arrangement.

Sparta, Athens’ major rival, and her allies soon got tired of paying for the far-away capital’s expenses. The ensuing wars between the Delian League, led by Athens, and the Peloponnesian league, led by Sparta, in the Peloponnesian peninsula seriously dented Athenian supremacy.

Later, in around 296-295 BCE, a native citizen of Athens, the tyrant Lachares, stripped the Parthenon’s massive gold-and-ivory statue of Athena the Virgin (Athena Parthenos) of her ornaments to pay his troops. This was rather like asking the Mexicans to pay for the building of a wall to separate them from the United States.

The temple to Athena later served as an orthodox church of St Mary the Virgin for 1,000 years and then as a mosque during the Ottoman occupation from 1458 to 1821. It has been used as a barricade and an arsenal, or storage place for gunpowder, by Greece’s enemies. In 1687 an Ottoman ammunition pile was ignited when the occupying power came under attack from the Venetians. The explosion blew the roof off and the temple has never been fully restored.

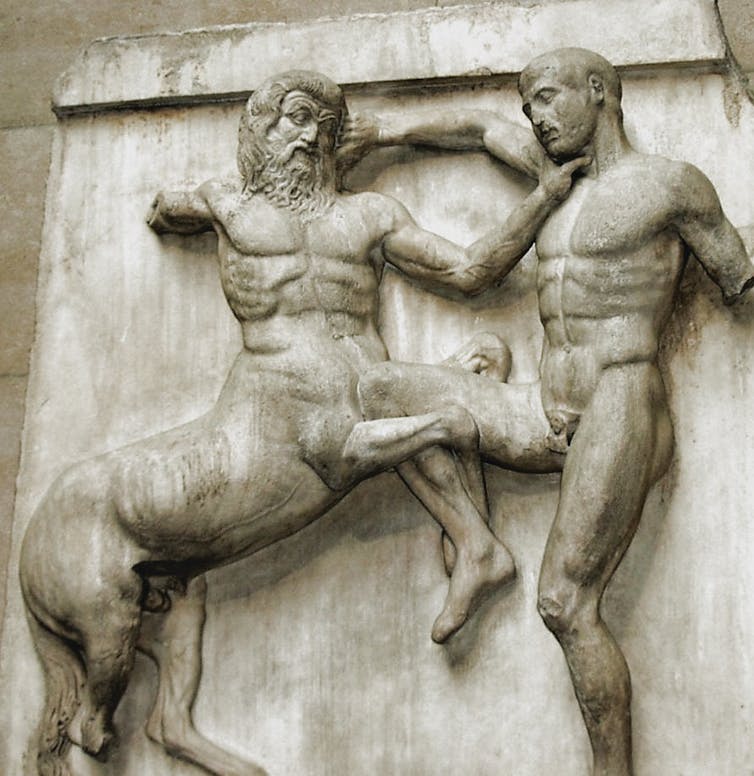

Its relics have been ransacked by collectors under the guise of keeping them safe. The most famous example is the Parthenon Marbles, sculptures which were removed to London in the early 1800s by Lord Elgin. They were acquired by “conservators” for the British Museum, where they still have their own dedicated display in the Parthenon Room 18.

After a long-term campaign by the Greek government, some of the Parthenon statues have recently been returned to the magnificent Acropolis museum. The history of re-purposing of the Parthenon thus runs the full gamut of Western civilisation’s ups and downs, and raises important questions about cultural hegemony, and the relationship between art, architecture and power, and who controls that power.

The power of symbols

The study of the western canon of Classical art and architecture is undoubtedly still relevant. The Greco-Roman civilisation was the source of so many modern European and New World institutions, in the areas of law, defence, agriculture and politics, to name a few.

As James Osterberg (better known by his stage name Iggy Pop) commented, reading Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire helped him “gain perspective” by showing him the parallels between the United States and the ancient Roman (and by extension Greek) past.

“America is Rome … All of Western life and institutions are traceable to the Romans and their world. We are all Roman children, for better or worse,” he said.

The Parthenon has long been upheld as a symbol of democracy. The ideal of rule by the people was established in Greece as a political system at the same time as the Parthenon was built, the mid-fifth century BCE. Pericles, the Athenian statesman who started the building of the Acropolis, also founded a limited democracy with voting rights for male citizens. However, he also limited Athenian citizenship to those with Athenian parentage on both their mother’s and father’s side.

More recently, Melina Mercouri, who has campaigned to have the Parthenon Marbles returned to Greece from the British Museum, has stated that they are “a tribute to democratic philosophy”.

But when we celebrate the survival of Athenian culture in the enduring symbol of the Parthenon, we should also remember the chequered history of the temple. And we should not forget Sparta, another ancient Greek city-state with its own distinctive culture and values, at whose expense the Acropolis was raised.

As with any survey of Western civilisation, only context can help us decide which elements of our cultural history are rightly celebrated, and which serve as monuments to other characteristics that are not so great.