Before committing more troops, the Australian government should be certain about the type of threat Islamic State (IS) poses and whether the Australian Defence Force has a clear and justified objective to tackle it. So far, our muddled mission to “destroy” IS is unlikely to work. Rather than dropping bombs, potentially killing innocent civilians, we need to contain the spread of IS and sever its supply lines and financial sources.

Over the past few weeks, Australian government officials have labelled IS as criminals, terrorists, militants or enemy combatants. While the correct labelling of threats may appear irrelevant, this have significant consequences for the development and application of appropriate responses. The lack of clear identification of IS means that we don’t yet really understand the threat to Australia and how we should respond.

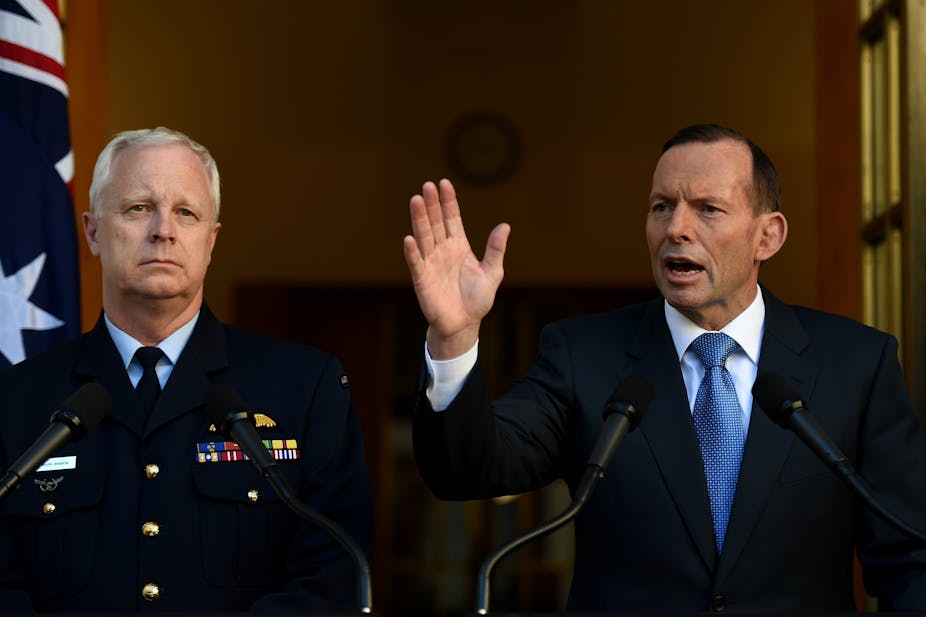

How the Australian government involves itself in the allied efforts to “destroy” IS could translate into Australia becoming a fully fledged terrorist target. Today’s announcement by Prime Minister Tony Abbott of a plot to behead an innocent Australian means we are well on the way to that.

What is the true nature of the mission?

This confusion has been reinforced in recent government statements. Prime Minister Tony Abbott, for example, in the space of a few sentences, called the group a death cult, a terrorist threat and a murderous movement. He stated:

This is essentially a humanitarian operation to protect millions of people in Iraq from the murderous rage of the ISIL movement … this movement is neither Islamic nor a state. It is a death cult reaching out to countries such as Australia … This is about taking prudent and proportionate action to protect our country and to protect the wider world against an unprecedented terrorist threat.

Attorney-General George Brandis had different views, particularly on the mission’s objectives. His main reason for military action seems to involve the ADF fighting “evil” on humanitarian grounds. He said that the apparent beheading of a British aid worker by IS militants served to demonstrate “how barbaric and evil these people are” and why Australia needs to be engaged in the fight against them.

In a further comment, Brandis disputed that Cabinet’s decision meant Australia was once more at war in Iraq. He said:

I don’t think it’s correct to describe what we are speaking of as a war. It is a mission, it is essentially a humanitarian mission with military elements, of course.

So according to the attorney-general we are not at war, but Australian Defence Force (ADF) chief Mark Binskin has other views. He believes IS can be defeated on the battlefield. Using terminology not typically used to explain military adversaries, Binskin said the jihadists were a “bunch of thugs” and Iraq needed to be given the military strength to defeat the organisation, which has seized control of the country’s north.

While the government has made no mention of committing ground troops, Binskin believes that Islamic State fighters are credible thugs requiring more than airstrikes. He added:

You will have to take them on the battlefield. There’s no doubt about that. That’s a part of their strength - their successes.

This still doesn’t offer a clear explanation of the threat to Australia. Nor do we appear to have solid justification for military involvement outside humanitarian grounds.

Yet the prime minister has leapt to support US President Barack Obama by committing Australian military personnel and equipment at an expense of some $500 million a year during a time of supposed “budget repair” back at home. This is on top of the additional $630 million already promised to security and intelligence agencies to “protect our shores” from IS.

Specifically, the Australian mission will involve fighter jets and about 600 troops and support staff, including Special Forces soldiers. These soldiers will be based in the United Arab Emirates on standby for action in Iraq. Some of the contingent is already on its way and more will follow in the next few days.

But why are we committing the ADF to fight IS in a fuzzy and potentially unsuccessful mission? There is no clear answer. Prime Minister Abbott, while not specifying a time-frame for the mission, says that there are “clear and achievable objectives” - that is, to drive IS “entirely from Iraq”.

For those thinking about joining IS, Abbott warned Australian Muslims they will be acting “against God” if they join the group. They would find themselves in more danger as a result of the ADF deployment to help destroy IS. The prime minister also warned that he could not guarantee “perfect success” or “risk-free operations”.

To many observers, much of rhetoric used by the government carries echoes of another failed mission with many obscure objectives. The last war left Iraq in disarray with well over 100,000 Iraqi civilians dead and costing the US $2 trillion and the lives of almost 4,500 troops. The eventual disengagement from the region, including from the bordering Syrian conflict, created a breeding ground for terrorism, which let IS develop and spread.

Yet other observers argue that the cost of standing back and failing to engage IS militarily will create an adversary that is even more fearsome and effective than al-Qaeda, the terrorist organisation that inspired IS.

Accepting the IS invitation to do battle

However, playing into the hands of IS with military intervention is even more flawed. A clever media strategy is helping IS incite violence between Muslim groups and military forces in the region, commit savage acts and temporarily lay claim to oil resources. By inciting a military intervention, the destabilisation in Syria and Iraq is supposed to create “regions of savagery” - or true chaos wrought by war - “where shell-shocked inhabitants willingly submit to IS to end conflict”.

If this is their real strategy, no military intervention will defeat the IS. A better solution therefore is to wait them out, contain them and allow them to implode. It is not a simple conflict but involves Sunni Muslim minority and Shia majority groups and multiple insurgencies that aren’t IS. We should not complicate this further with US and allied military intervention.

A long-term policy (such as firm containment) should be designed to confront IS at every point where it shows signs of expanding outside Syria and Iraq. Isolating IS will weaken its ability to meet the basic needs of the communities it controls and cut its financial lifeline to the profits of oil produced in Syrian and Iraqi oilfields and exported through Turkey via black marketeers. As foreign jihadists appear to be guided to Syria via Turkey, it would also be valuable to work with Turkey to ensure IS is denied political support and that there is, in the near term, logistical capability to close these borders.

As barbaric as they are, the IS tactics are not random. Its methods appear to be rooted in a calculated plan to entice and engage allied military forces.

We are still confused about the threat IS poses. So why are we getting more involved in its twisted strategy?

This article was updated in the hour after first publication.