Review: Fatal Contact: How Epidemics Nearly Wiped Out Australia’s First Peoples by Peter Dowling (Monash University Publishing)

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of deceased people.

As Peter Dowling reminds us in his introduction to this book, violence on the colonial frontier accounted for many thousands of deaths among the First Peoples — a truth unremembered in a process of historical amnesia labelled the “great Australian silence” by anthropologist W. E. H. Stanner.

Australia’s sense of its past in collective memory, Stanner said in his famous 1968 Boyer lectures, was:

a view from a window which has been carefully placed to exclude a whole quadrant of the landscape […] a cult of forgetfulness practised on a national scale.

A great deal has shifted in our understanding of the past since Stanner shocked the historical profession into a halting engagement with the truth of Australia’s settlement.

Yet, as historian Billy Griffiths pointed out in the anthology Fire, Flood and Plague, a key part of the “great Australian silence” has been our continued willingness to see pandemic disease that eliminated the great majority of the First People as “inevitable and apolitical”.

Read more: Friday essay: the 'great Australian silence' 50 years on

In the face of the current pandemic, playing out on a global stage, Griffiths writes, we can observe that “it is not only about microbes; it is also about culture, politics and history”. The radically different consequences of this pandemic as experienced by different peoples has shown us we cannot blithely assume spread of disease is without responsibility.

This is what Dowling would have us understand in his timely and meticulous account of “the greatest human tragedy in the long history of Australia”. He examines the recurring outbreaks of fatal epidemics of smallpox, measles, syphilis, influenza and tuberculosis (TB), which “nearly wiped out Australia’s First Peoples”.

Catastrophic impact

At the time of colonisation, these diseases were so endemic in Britain that a high degree of immunity existed in the population, as well as medical strategies to control epidemic spread. But in the virgin-soil communities of Australia’s First Peoples, everyone was susceptible, with no-one spared. So there was no-one to provide basic needs for the sick.

The impact was catastrophic, as illustrated in the multiple accounts of the smallpox outbreak at Sydney Cove in 1789. This is widely known about now, but a wave of epidemics, including smallpox, continued to decimate the First Peoples well into the 20th century.

Alongside smallpox, syphilis also reached epidemic proportions in the Sydney region in the first few decades of settlement, gradually extending into every corner of the continent.

The scourge of syphilis was apparent in the early colony in Tasmania and a major contributor, along with influenza, to the rapid mortality that had all but eliminated the peoples of the south-eastern quadrant of the island by 1830.

It was in Victoria where the magnitude of the disease was most apparent. In 1839, a cohort of Aboriginal Protectors were appointed to various districts across Victoria. They all reported overwhelming syphilis infection, accounting for as many as “nine out of ten” of the many sick and dying.

One reported of the First People in his district “the most extensive ravages […] will render them extinct within a few years”.

Another despairingly complained “no medicine has been placed at my disposal”.

Worst in camps

Epidemics reached into isolated First People’s communities well out of sight of authorities — the Spanish Flu of 1918 managed to spread its deadly tentacles into communities of the Western Desert. However, outbreaks were much more likely in the government-supervised camps, reserves, missions and stations, where dispossessed First Peoples were forcibly relocated.

Uniformly, these places of concentration had overcrowded and inadequate housing, low nutritional diets and bad water supply, combined with individual distress and depression — conditions favourable to the incubation and spread of diseases.

The First People’s high susceptibility to disease, Dowling argues, was probably a consequence of chronic untreated TB among those forced into camps and settlements.

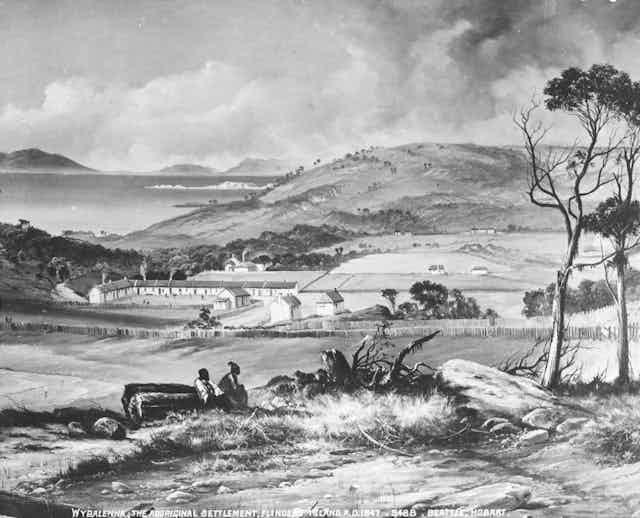

He examines the settlement on Flinders Island in Tasmania between 1832 and 1847, which became infamous for its horrendous death rate, mythologised by the colonists who had expelled these people simply due to their “pining away”.

The records examined by Dowling show these people actually died of either TB itself or an associated respiratory illness worsened by TB’s immunosuppressant effects.

TB was also known to have been an efficient killer in the Victorian settlements at Lake Hindmarsh and Coranderrk: the attributed cause of more than 30% of recorded deaths in those places between 1876 and 1900. At these same settlements, a measles epidemic in 1874-5 killed 20% of people.

It is no coincidence this was the same story as at the notorious concentration camps for dispossessed Boers the British created in South Africa at the end of the 19th century, where various epidemic diseases were allowed to rage.

Read more: The COVID-19 crisis in western NSW Aboriginal communities is a nightmare realised

As I write, I am acutely aware most communities of First Peoples have the lowest vaccination rates in the nation — even though the government has assured us repeatedly vaccination for these most vulnerable communities was their highest priority.

In despair, I repeat the mantra: the past is not even past.