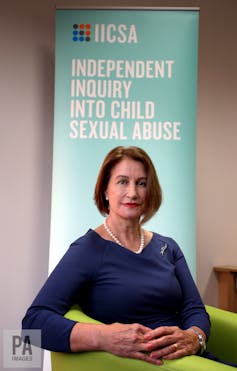

The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, set up to investigate allegations of abuse carried out within public institutions in England and Wales across several decades, seems to bounce from one crisis to the next. The latest development is chair Alexis Jay’s new “strategy”. She announced a changed approach in the wake of concerns that the inquiry has become unmanageably large.

But Jay is adamant that the inquiry does not need to be scaled back. Instead, its focus will be sharpened by aligning it to four major themes of investigation:

*Cultural – the attitudes, behaviours and values within institutions that have prevented child sexual abuse from being investigated;

*Structural – the legislative, governance and organisational frameworks in place, both within and between institutions;

*Financial – the funding and resource arrangements for relevant institutions and services;

*Professional and political – the leadership, professional and practice issues for those working or volunteering in relevant institutions.

Full details of further changes to its existing approach are expected within a few weeks. It is likely the number of public hearings will be reduced to those dealing with areas deemed particularly necessary, with many being replaced by discussion forums and case reviews. The selection of these areas is likely to be extremely controversial among survivors, many of whom have waited years for their voices to be heard.

Views will be taken from those affected by the inquiry’s work prior to any decisions being taken, but Jay appears to be taking a more assertive approach to influence from all parties. She recognised that “they may not always support the decisions we make” and stated bluntly that the inquiry will “scrupulously preserve its independence from all parties, applying its best judgement without succumbing to undue influence from any person, group, special interest or institution”.

Spiralling scope

What has been particularly striking in this case is the extent to which pressure from survivors, the public and the media has repeatedly influenced the very nature of the inquiry.

External criticism has played a direct role in the departure of the first two inquiry chairs. It has also contributed to the expansion of the inquiry’s scope, which is now enormous and was cited as one of the reasons for the resignation of the third.

Set up to examine the extent to which institutions in England and Wales have taken seriously their responsibility to protect children, it is now looking at a vast range of public and private institutions. These include local authorities, the police, the BBC, hospitals, schools, the armed forces, religious organisations and charities. It is also investigating allegations of abuse involving “well known people” in various aspects of public life.

Under pressure

When the inquiry was first convened in 2014, it was intended to be an independent panel inquiry. However, following seven months of media criticism and statements from survivors that they would not participate unless the inquiry was given greater powers, the original panel inquiry was dissolved and the current IICSA was convened.

The new public inquiry brought with it greater powers. It can compel witnesses to give evidence under oath. The presumption is also that the hearings will be held in public.

At the same time the government significantly expanded the terms of reference in light of feedback from survivors. While this was welcomed by those pressing for change, it has resulted in a much more complex and drawn-out process.

The terms of reference are a crucial factor in determining what an inquiry will do, how long it will last and whether it will be a success. If the terms of reference are too narrow, the government may look like it is avoiding difficult political issues by restricting the ambit of the inquiry. If the terms of reference are too wide, the result may be a significantly protracted and complex inquiry – which might also distract from the essential issues.

Many feel that the IICSA has become too far-reaching and fear that, by trying to satisfy everyone, the government has risked ultimately frustrating the objectives of the inquiry. The failure to get the model right from the outset, followed by repeated backtracking on earlier decisions, has risked seriously damaging public confidence in it.

Timely consultation and engagement is crucial, but that must be balanced with effective management of expectations. Resources are finite and difficult decisions have to be made about balancing the survivors’ need to be heard and their calls for justice with the need to focus on learning lessons.

This public inquiry has a vital role to play in holding those in authority to account and protecting future generations of children. Seeking to please everyone risks ultimately producing an unworkable inquiry that pleases no one.