The final run-off of the Brazilian presidential elections, to be held this weekend, represent a decisive moment for Latin America’s largest nation. No matter who wins, will the newly elected government implement progressive policies leading to higher growth and macroeconomic stability?

Place your bets

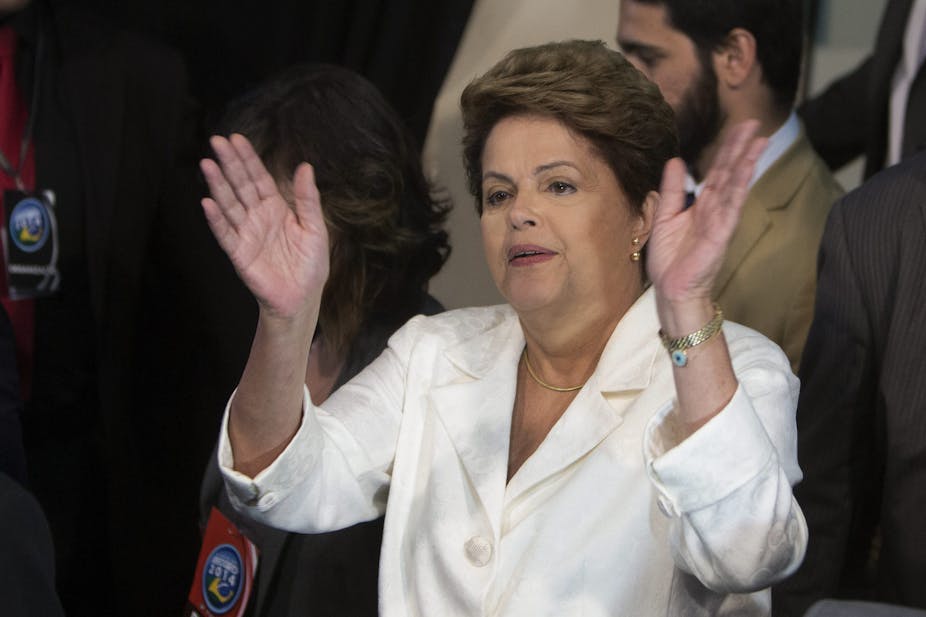

In one corner is the incumbent, Dilma Rousseff. She is seeking re-election and representing the centre-left Workers’ Party (PT), which has been in power since 2003. Rouseff’s government has been marked by strong state intervention, deepening the statist moves inside her party since 2006.

Aecio Neves is opposing Rousseff. He is a former senator, twice governor of Minas Gerais (Brazil’s second most populous state) and grandnephew of Tancredo Neves, a champion of Brazil’s re-democratisation process and the first president after the end of the military dictatorship in 1985. Neves belongs to the Social Democrats (PSDB), the opposition centre-right party of former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso, under whom major structural reforms were conducted between 1994 and 2002.

In the first ballot on October 5, Rousseff received 41.6% of the vote, ahead of Neves with 33.5%. The lack of a clear majority meant that a second ballot was scheduled between the two candidates.

Rousseff’s government has been marred by allegations of corruption – the latest one involving the state oil company Petrobras – and poor economic performance. Also, widespread street riots in 2013 displayed the population’s dissatisfaction with the status quo.

Given the above, one would expect the opposition to win in a landslide, yet this was not the case. Why?

A lie told often enough becomes the truth

In Road to Serfdom, Friedrich Hayek pointed to the disregard of interventionist governments for the truth. As long as it serves the party’s project of power, noble lies would be a necessary evil: lies are revolutionary.

Rousseff is clearly fond of this idea. Once a fierce advocate of Marxism and the armed guerrilla movement during Brazil’s military rule, Rousseff and her acolytes in the Workers’ Party have consistently distorted the truth to secure the party’s hold on power.

In a shamelessly negative campaign, the Workers’ Party has used open-ended propaganda to spread fear that the opposition, once in power, would scrap the social advances experienced in the last commodity boom. In particular, it claims the opposition would terminate the much-praised conditional cash-transfer scheme, Bolsa Familia.

In response, Neves has repeatedly and publicly declared that under his presidency, Bolsa Familia would be expanded in size and resources. Also, the original conditional cash-transfer scheme was first implemented at a national level in 2001 by Neves’ Social Democrat party.

Unfortunately, the propaganda has been very effective. The Workers’ Party performed extremely well in the first ballot in Brazil’s north/northeast region, where most of the Bolsa Familia’s 11 million beneficiary families – representing almost one-quarter of the Brazilian population – are concentrated.

Let them eat cake

Despite the current government’s rosy depiction of the economy, the reality is much gloomier.

Inflation, an old public enemy since the hyperinflation years of the 1980s and early 1990s, has started to rise uncontrollably. The latest consumer price index annual rate at 6.75% is way over the 4.5% target rate and has dangerously busted the 6.5% inflation target ceiling determined by the central bank.

The stubborn climb in Brazil’s inflation rate is a direct consequence of an ill-devised combination of monetary, fiscal and trade policies. The current government has undermined fiscal efforts to curb public spending. And with a tax burden ratio of more than 35%, not much can be fixed through raising more public revenues.

With regard to monetary conduct, the government has constantly undermined the autonomy of the central bank – which favours a more hawkish approach – relying instead on erratic state intervention such as energy price controls. Also, trade protectionist measures to “assist” government-selected domestic businesses have acted against the inflation fight.

Quite tellingly, the latest absurdity from the incumbent government on how to tackle inflation was the suggestion that Brazilians should swap meat for eggs in an attempt to curb rising meat prices.

Yes, we can

The government’s propaganda, filled with threats and a misleading picture of the economy, seems to be losing its resonance with the public. Recent polls indicate that Neves is slightly ahead in a tight second-round campaign.

Neves won the much sought-after support of Marina Silva, who ran third in the first round of voting. His policy platform relies on responsible fiscal spending, less government intervention and a credible, orthodox fight against inflation.

Arminio Fraga, Neves’ would-be treasurer, for instance, is a respected economist with deep experience in financial markets and central banking. A former central banker under the second presidential term of Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Fraga was recently tipped to lead the International Monetary Fund.

The run-off presents two distinct options for Brazil. One is the dangerous path towards state intervention and irresponsible policies. The other is the path of change towards accountable governance and a new round of much-needed structural reforms. The question remains: quo vadis [where are you going], Brazil?

The author will be speaking at a series of briefings on the implications of the election result, organised by the Centre for Independent Studies (Sydney, November 3) and by the Australian National Centre for Latin American Studies (Melbourne and Canberra, November 6).