There’s good news about asthma in the report card “Asthma in Australia 2011” published last week by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). But there are also some sobering facts about heath-care equity.

After a period of rapidly increasing prevalence in the 1980s and 1990s, there’s now convincing evidence the occurrence of asthma has been falling, at least in children and young adults, since the late 1990s or early 2000s.

This follows other good news: rates of hospitalisation and of death due to the disease have been falling for nearly two decades now.

But there’s another side to this story – asthma is still more common in Australia compared with most other countries: one in 10 Australians has asthma.

And people living in more disadvantaged localities are more likely to have asthma, to be hospitalised for it and to die from it than people living in more advantaged areas.

Even more worrying, these differences are increasing.

Any answers?

How can we explain all this? Why is asthma less of a problem now than it was 20 years ago? And why is it more common and more troublesome among people living in disadvantaged areas?

There are no definitive answers to these questions, mostly because we don’t yet know what causes asthma.

But there are numerous theories, some of which are amenable to testing. In general, randomised controlled trials (the highest level of evidence) haven’t yielded evidence to support preventive interventions based on any of these hypotheses.

In particular, allergen avoidance, as currently practiced, doesn’t seem to prevent the onset of asthma. Nor does fish oil supplementation. Hence, neither of these is currently recommended.

Since we don’t know what causes asthma, we can’t say why the prevalence increased in children and young adults during the 1980s and 1990s or why it has subsequently decreased.

We can say genetic factors are unlikely to explain changes over such a relatively short period of time. And while environmental or lifestyle factors are implicated, specific culprits remain unknown.

What we do know

In fact, it’s likely asthma isn’t one simple condition with a single cause. Rather, the condition we commonly call asthma is probably the end result of a number of different disease processes, with diverse causes.

And it’s likely that only some of these entities have changed in prevalence over time.

The reduction in deaths and hospitalisations attributed to asthma has been evident for longer than the change in the prevalence of the illness.

While the more recent changes may partly be attributable to a reduction in the number of people who have the disease, it’s likely there have also been improvements in outcomes among people who have the disease.

This may be due to changes in the nature of the disease but could also been because of improvements in the use of medications that we know do have beneficial effects in people with asthma.

And the cost of these treatments may be one of the factors contributing to worse outcomes among people living in disadvantaged areas.

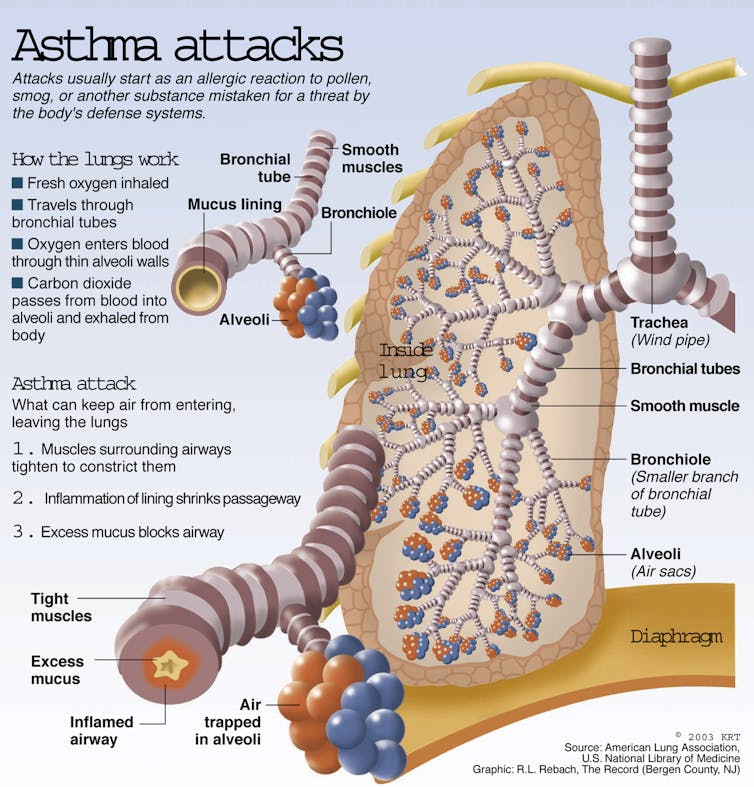

People with persistent asthma, who are at greatest risk of adverse consequences, are recommended to regularly and indefinitely take medications to control the inflammation that underlies the disease (so-called “preventers”).

For those individuals and families without access to Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) medications at concessional rates, the monthly cost is substantial and, over the course of a year, represents a barrier to the regular use.

Asthma is a common chronic disease in Australia: recent improvements in population data shouldn’t distract us from the need to look for ways to prevent this disease in people who are at risk.

We also need to ensure that all Australians with asthma share in the benefits of effective disease management and improved outcomes.