Halfway through Bret Easton Ellis’s first novel in 13 years, The Shards, the 17-year-old narrator, Bret (a fictionalised version of the author) pitches to a producer, Terry Schaffer.

This Bret, who is working on the debut novel the real Bret published in 1985 – Less Than Zero – describes the scenario he has developed.

[A] boy, his friends, young people in L.A.; sexy, a little bi, drugs, someone is killed, there’s a chase, violence and bloodshed, a mystery that the boy solves or maybe not, I preferred the downer ending but could make it upbeat as well, I’d offer, we could negotiate that.

To a certain extent, this pitch, which the narrator pretty much makes up on the spot, mirrors the plot of Less Than Zero (which, despite some biographical overlap, Ellis has always considered a work of fiction).

With a few changes, the scenario could also double as a summary of The Shards. The crucial difference is that this new novel – in ways Ellis’s debut does not – dissolves the lines between fact and fiction, reality and fantasy.

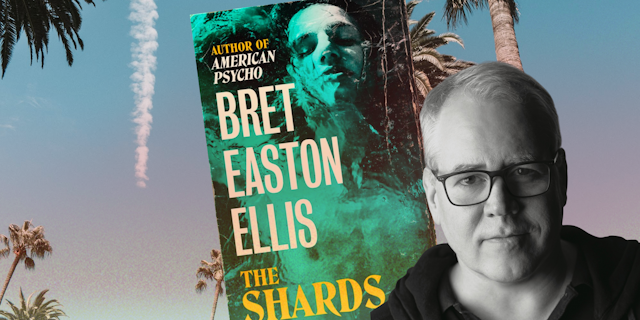

Review: The Shards – Bret Easton Ellis (Swift Press)

Writerly imagination in overdrive

The story is set in the autumn of 1981 and revolves around a cluster of wealthy students enrolled at Buckley College, an exclusive Los Angeles prep school.

Bret, who is gay but closeted, is dating Debbie Schaffer (who has justifiable doubts about her boyfriend’s friendships with Ryan Vaughn and Matt Kellner), and is friends with two teenage sweethearts, Susan Reynolds and Thom Wright.

The Bret who is writing this novel then introduces two more characters – a student named Robert Mallory and a serial killer called The Trawler – into the mix.

Not long after, Matt goes missing. The fictional Bret’s writerly imagination goes into overdrive. He suspects Robert is responsible, and that he is The Trawler. Things quickly spiral out of control.

As Ellis’s fans will anticipate, his latest is full of pop culture references (the Buckley clique are big New Wave fans), sex and drugs, and acts of grotesque violence rendered in tonally neutral prose. Some cultural commentary, too, on the purported perils of political correctness. Think: Joan Didion meets Brian De Palma.

When it comes to content, The Shards, with its cast of hedonistic and disaffected adolescents, aligns with three of Ellis’s earlier L.A. novels: Less Than Zero, 1987’s The Rules of Attraction, and the sequel to his debut, 2010’s Imperial Bedrooms.

In terms of length, however, The Shards, which is 600 pages long, is closer to Ellis’s New York fictions: 1991’s American Psycho (which I believe is the most important novel of the 1990s), and 1998’s Glamorama (easily, for me, the best novel of the 1990s).

What, though, of form? To answer that question, we should turn to what once seemed a relative outlier in Ellis’ fictional oeuvre, 2005’s Lunar Park. This is from the first chapter:

It was to deal primarily with the transforming events of my childhood and adolescence, ending with my junior year at Camden, a month before Less Than Zero was published. But even when I simply thought about the memoir it never went anywhere (I could never be honest about myself in a piece of non-fiction as I could in any of my novels) and so I gave up.

In an autofictional move that prefigures the central conceit of The Shards, Lunar Park’s narrator – a fictional version of Ellis in middle age – is discussing a memoir he didn’t write. This Ellis says he “had even given it a title without having written a single usable sentence: Where I Went I Would Not Go Back”.

Ellis’s interest in the creative treatment of actuality emerges in these extracts, as does his willingness to mine his youth for inspiration.

Read more: The case for American Psycho: why this controversial book (sold here in shrink wrap) still matters

The ‘fake enclave’ of the novel

Now consider what Ellis says about that most recognisable of literary forms: the novel. This is from White, the contrarian essay collection he published in 2019. Pay attention to his descriptions of Lunar Park and Imperial Bedrooms:

The desire to write prose had kept pulsing faintly within me for years but not within what I now saw as the fake enclave of the novel. In fact I’d been wrestling away from the idea of “the novel” for more than a decade, as evident in the last two books I published: one was a mock memoir wrapped within a horror novel, and the other was a condensed autobiographical noir I pushed through painfully during a midlife crisis, a story about my first three years back in Los Angeles futilely working on movies after I’d lived in New York for almost two years.

Ellis’ dissatisfaction with the novel is palpable. “For those past five years I had no desire to write a novel and had convinced myself I didn’t want to be constrained by a form that did not interest me anymore.”

But why, given his apparent lack of interest in the form, did Ellis bother writing another novel? This is the explanation he gives in the “preface” to The Shards, which, to repurpose Ellis, reads as an expansive L.A. noir wrapped up as an ostensibly honest memoir:

It wasn’t until 2020 that I felt I could begin The Shards, or The Shards had decided that Bret was ready because the book was announcing itself to me – and not the other way round.

The Bret speaking here is a fictional, older version of the novel’s narrator. He is reflecting on the traumatic events of The Shards:

I hadn’t reached out to the book because I spent so many years pushing myself away from The Trawler, and Susan and Thom and Deborah and Ryan, and what happened to Matt Kellner; I had relegated this story to the dark corner of the closet and for many years this avoidance worked – I didn’t pay as much attention to the book and it stopped calling out to me. But sometime during 2019 it began climbing its way back, pulsing with a life of its own, wanting to merge with me, expanding into my consciousness in such a persuasive way that I couldn’t ignore it any longer – trying to ignore it had become a distraction.

(I should note, there is also a preface to the “preface”, where the “real” Bret – the one writing the novel in our hands, as opposed to the book within the book – thanks the reader for sticking with him over the years.)

It seems that, try as he might, Bret Easton Ellis - imagined or actual - simply cannot get away from the novel.

He admits this in White, while harking back to his experiences in the 1980s and 90s. “I rarely gave interviews between book publications because part of the process was still mysterious to readers,” Ellis ruminates, “with a kind of secret glamour that added to the excitement with which books were once received, whether negatively or positively.”

Read more: How autofiction turns the personal into the political

Exploring analog v digital worlds

To his credit, Ellis, who is quite cranky these days, appreciates that things are different now. As he argues in White:

But novels don’t engage with the public on that level anymore. I’d wistfully noted the overall lack of enthusiasm for the big American literary novels […] but I’d also realized that’s nothing to worry about. It’s only a fact, just as the notion of the great American studio movie or the great American band has become a smaller, narrower idea. Everything has been degraded by what the sensory overload and the supposed freedom-of-choice technology has brought to us, and, in short, by the democratization of the arts.

For better or worse, there is, in Ellis’s reckoning, no going back. Hence the steps he took:

I started feeling the need to work my way through this transition - to move from the analog world in which I used to write and publish novels into the digital world we live in now (through podcasting, creating a web series, engaging on social media) even though I never thought there was any correlation between the two.

Ellis knows better now. The Shards, which started as a year-long, hour-by-hour performance hosted on Ellis’s podcast is proof there are points of correlation between the analog and digital realms, which he also defines in relation to - of all things - the concept of Empire:

If Empire was about the heroic American figure - solid, rooted in tradition, tactile and analog – then post-Empire was about people who were understood to be ephemeral right away; digital disposability doesn’t concern them – they’re rooted in traditions created by social media, which is solely about exhibition and surface, and they don’t follow a now dated path of cultural development.

This helps us understand The Shards, which is the best and most ambitious novel Ellis has published since Glamorama. Forget what Ellis said about being done with the novel. His latest, which unfurls, as the narrator states, across the “deep span of empire”, confirms that Ellis remains committed to the form, and the opportunities it affords him.

The Shards is a bold attempt to understand how the analog and digital interact. This accounts for the novel’s countless, obsessive descriptions of outmoded forms of analogue tech: the cassette, the Betamax, and, most tellingly, the typewriter. It also explains Ellis’s bravura manipulation of genre (the age of the digital, as we know, is one where once-stable systems of classification tend to collapse).

With his latest, Ellis is, in essence, attempting to refashion and – to crib from the Trawler – remake the (analog) novel in our contemporary (digital) age. I think he succeeds. Others may disagree. Either way, The Shards is a timely reminder this is a writer willing to take risks.

Whatever one thinks about the other Brets floating around, it’s good to have this version of Bret Easton Ellis back.