After 125 years in the same spot, the bronze statue of slaver Edward Colston lies at the bottom of Bristol Harbour. Unsurprisingly, many were unhappy with the move by Black Lives Matter protestors. Only a day later a group of dissenters attempted to fish the heavy statue from its watery grave.

It would seem that such attempts at retrieval are as futile as resisting the long-awaited reckoning on the nature and meaning of public monuments across Britain. Colston’s removal has featured prominently in the international press and sparked debates about history and erasure across the world. It has also prompted widespread conversation around which statues and monuments should be scrutinised for their celebration of violent colonialism and white supremacy.

The significance of this moment cannot be overlooked by art historians. Monuments demonstrate how visual and material culture can be weaponised to obscure the violence that characterised British colonial expansion. From single statues to elaborate multi-figure designs, monuments represent a visual culture that has been mobilised as a means to celebrate and justify white supremacy throughout history. To this end, they did not solely rely on sculptural statues of colonial “heroes” such as Colston, but also other types of visual communication to misrepresent empire as a noble and heroic pursuit.

Artistic state propaganda

Sculptures of allegorical figures are the omnipresent artistic symbol of state propaganda and oppression on sculpted monuments. Fictional female figures such as “Victory”, “Peace”, “Justice” and “Britannia” gained popularity during the most aggressive period of British imperial expansion in the 18th and 19th centuries.

It is important that the role of these figures is not forgotten in this current moment. Firstly, because they demonstrate how monuments enabled sculptors to not only commemorate the deceased, but also to propagate the message of British colonialism and white supremacy for future generations. Secondly, because understanding them enables the public to recognise how visual culture can obfuscate state oppression. The “Victory” figures that appeared on British monuments in the 18th century were reused en masse for Confederate monuments over a hundred years later.

It was not a coincidence that, ahead of the civil rights protest, Bristol City council decided to cover Colston’s statue under a canvas. Much like history as a discipline itself, monuments are not neutral records but revisionist objects that mobilise art as a means to oppress. Acknowledging them as state-sponsored attempts to transform slavery and genocide into palatable subjects for public consumption exposes them as a visual accompaniment to Britain’s violent programme of colonisation.

Campaigns for removal

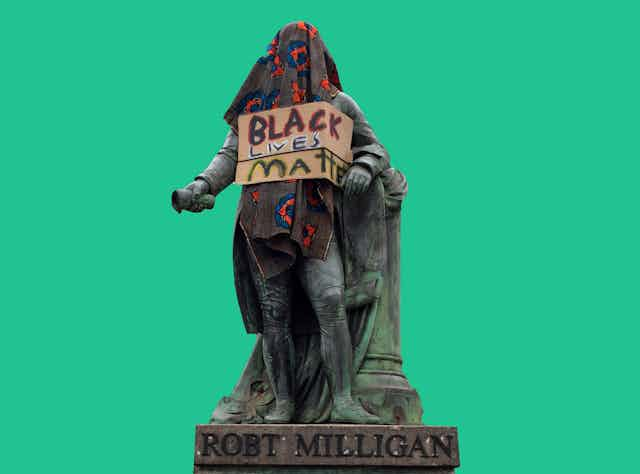

More statues commemorating white perpetrators of colonial atrocities are coming down daily, such as that of Leopold II outside Antwerp Museum in Belgium. New resources are also being developed to identify which should be next. The statue of slaver Robert Milligan has already been removed from outside the Museum of London Docklands. The decision was made by the Canal and River Trust in response to to petitions calling for its removal, showing that institutions can and should take decisions into their own hands.

However, those advocating for removal are increasingly met with the now-familiar argument that such moves represent an erasure of history. It’s an argument that has been firmly established in debates around Confederate monuments in the United States. Its an argument that has become louder in the UK over the past few days.

Over the coming weeks, figures from British history will be scrutinised and judged in an unprecedented way. This process will educate more people on the real history of Britain and bring new meaning to the monuments people walk by daily. This will hopefully, as the historian David Olusoga has argued, achieve tangible results where previous campaigns have failed.

London’s mayor, Sadiq Khan, has announced that he will be establishing a Commission for Diversity in the Public Realm to review London’s landmarks. But the move echoes the move by New York City mayor Bill de Blasio in 2017 to establish a Mayoral Advisory Commission on City Art, Monuments, and Markers, which recommended only one removal. This was monument to the torturer James Marion Simms, who in the 19th century performed horrific experiments on enslaved black women. Rather than being fully removed, it was relocated to a public cemetery in Brooklyn. There are fears that there will be similar outcomes in the London review.

Bolstered by the recent protests against anti-Black racism and state violence, public art continues to be reckoned with across the world, with ongoing campaigns such as #RhodesMustFall in Oxford and Take Em Down Nola in New Orleans, US.

Allegorical figures are one of the ways that monuments fictionalise history through visual culture. Understanding the role art played as a sanitiser of violence shows that destroying or removing monuments from public view does not erase history. Instead, monuments were designed to do just that by obfuscating state oppression and white supremacy through a thin veil of sculptural order.