The health system that Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari inherited is not performing at an optimal level. It is a fragmented system, with poor governance at the primary healthcare level and weak collaboration and co-ordination.

Buhari has since promised to revamp Nigeria’s health sector. Setting up efficient and functional performance management and clinical governance systems will go a long way in improving the quality of services delivered and co-ordinated by the health ministries and the hospitals across the 36 states.

But one major challenge the Buhari administration will grapple with is how the health sector is funded.

Although Nigeria is not regarded as a donor-dependent country, most critical public health interventions in the country are largely funded and implemented by donors. With a huge debt burden and depleted foreign reserves, the government faces the challenge of how to creatively source funds to provide critical public health services and sustain ongoing programs to save the lives of women and children.

Poor support from government

In 2010, the Nigerian government made commitments to release US$3 million annually to procure family planning commodities. This would be matched by contributions from donors. In 2012, at the London Family Planning Summit, the government made an additional commitment of US$8.35 million annually for four years for reproductive health commodities, including contraceptives.

But these commitments have not, to a large extent, been met by the government. Poor funding of key public health programs has remained a concern to health advocates. Like Ghana, which graduated to medium-income country a few years ago, Nigeria now has to look for alternative sources of funding other than official development assistance and grant aid.

In the spirit of transferring responsibilities to the home government, some bilateral donors such as USAID have gradually been withdrawing part of their financial support for HIV/AIDS programs. The gradual withdrawal is to allow federal and state governments to take more responsibility in funding public programs, which is part of their current engagement plan with Nigeria.

Donor funding is running dry

Despite the pervasive poverty, Nigeria is not a poor country that needs donors to stand on its feet. While donor agencies have no immediate plans to withdraw support from Nigeria completely, their focus is to support the government in building and strengthening institutions and structures that will help deliver good governance.

And following the rebasing of the Nigerian economy and the resultant upgrade from a low-income country to a low-medium income, most donor countries no longer see Nigeria as a country that needs grant aid for financing critical public health interventions.

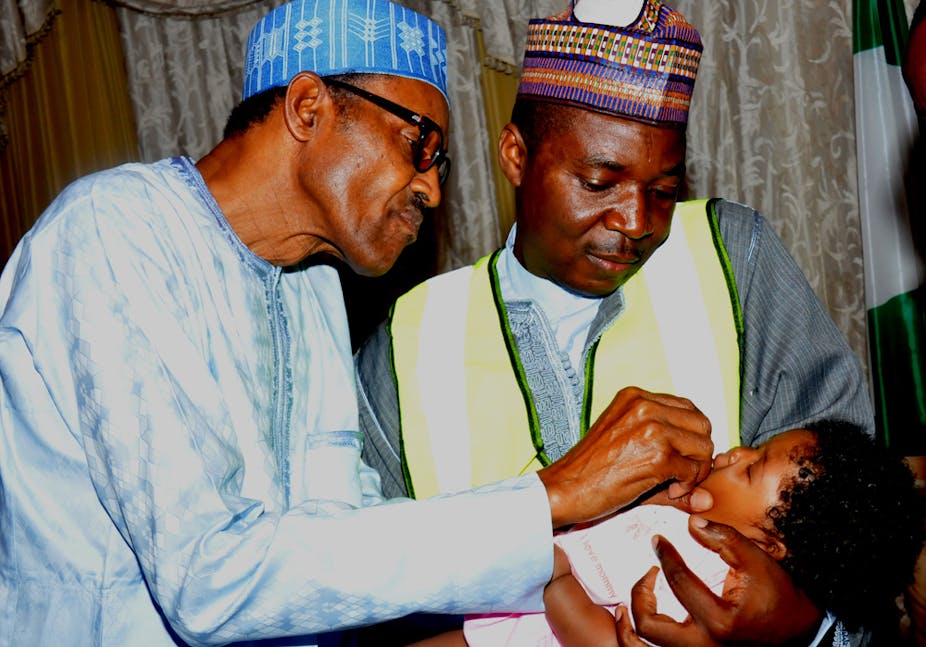

With this upgrade, Nigeria no longer qualifies as a recipient of grants for purchasing vaccines and supporting routine immunisation services from the GAVI Alliance. The reality hit home a few months ago when it became obvious that Nigeria could not set aside funds for the purchase of vaccines for children in 2015.

It took the intervention of Bill Gates, who is committed to the eradication of polio virus in Nigeria, to strike a deal through which the soft loan provided by the Japanese government and World Bank could be converted to grant aid if some key deliverables are achieved by the federal and state governments.

High expectations

In the last couple of years Nigeria has attracted considerable attention from the global health community for the wrong reasons. It has one of the worst health indices in Africa despite its leadership position on the continent.

Nigeria records about 800,000 under-five deaths every year. This accounts for about 11% of total global under-five deaths. Up to 40% of these deaths are from vaccine-preventable diseases and can be averted through routine immunisation for children and infants.

The country’s 2015 millennium development goal targets is to reduce under-five mortality to 70 deaths for every 1000 live-births and 250 mothers dying for every 100,000 live births. But the findings of the current National Demographic and Health Survey show that under-five mortality is 128 per 1000 live births. And the maternal mortality rate stands at 576 deaths for every 100,000 live births.

Nigeria also has the highest burden of malaria globally, and a high burden of HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis – among others. Non-communicable diseases like diabetes, hypertension and cancers are also on the rise.

Expectations are high that Buhari will bring a turnaround. Hope is rising that things will change for good.

One of the first steps is to find new ways to fund the healthcare sector. One of Buhari’s options to increase the fiscal space to improve domestic financing of critical health programs will be strengthening and enforcing tax regimes.

Buhari will need to sustain and deepen the current partnerships between the government and Private Sector Health Alliance of Nigeria. Through this, private sector resources have been used to finance healthcare interventions across different states in the country.

Innovative funding mechanisms such as a sin tax and a tax on phone calls need to be explored. The funds earmarked for basic healthcare services in the 2014 National Health Act need be effectively used when operational.

If, after four years, little change is seen in the quality of health services delivered or there is no progress in improving the health status of Nigerians, Buhari will go down as a leader who made promises that were not delivered.